Because I am known around The New Yorker offices as someone whose interest in watches occasionally elicits polite concern and the kind of side-eye usually reserved for men who won’t stop explaining cable management, it was perhaps inevitable that I would be assigned the Jeff McMahon story. When word spread that a 64-year-old writing instructor at Prospect College in Redondo Beach had triggered a watch-related disturbance of almost mythic proportions—drawing hundreds, then thousands of people into a crusade to “fix” his collection—I was dispatched to investigate how a private obsession metastasized into a civic emergency.

I visited McMahon during winter break. His wife, a middle-school teacher, and his twin daughters, high-school sophomores, were safely elsewhere, leaving him alone with his thoughts, his watches, and whatever demons had learned to tell time. He answered the door wearing black travel pants with zippered pockets and a black T-shirt. Nearly six feet tall, close to 230 pounds, bald, square-jawed, with the squint of a man perpetually assessing lug-to-lug ratios, McMahon resembled a retired linebacker who had traded blitz packages for forum debates.

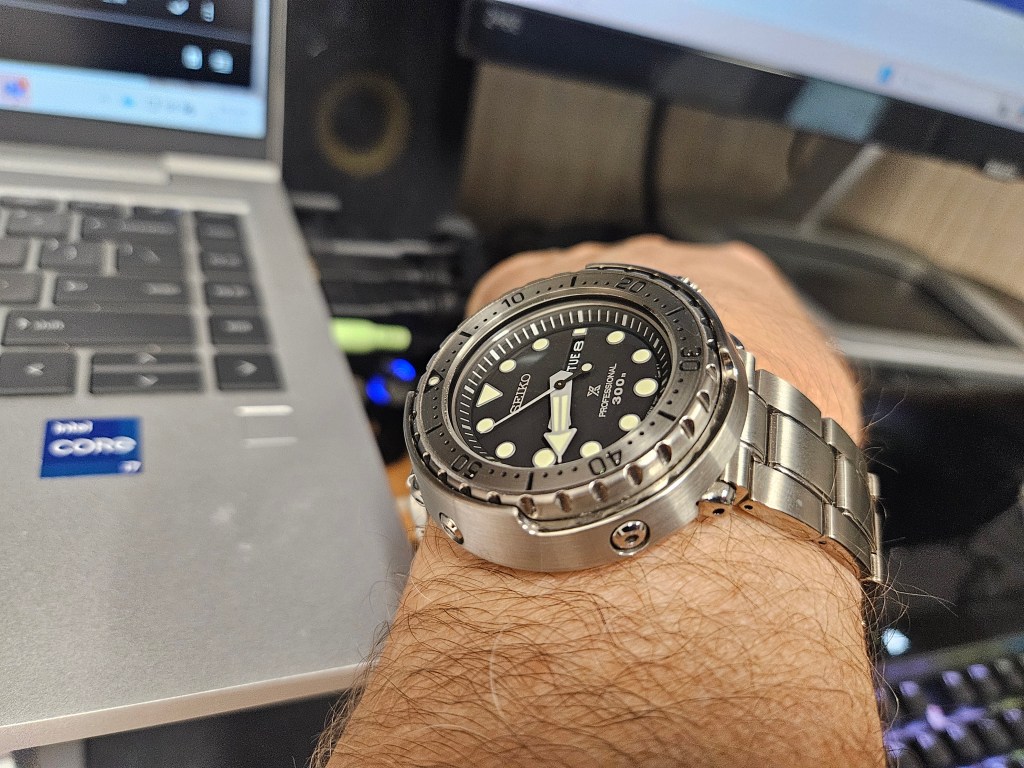

Naturally, I clocked the watch immediately: a third-generation Seiko MM300 with a blue dial on a waffle strap.

“It looks right on you,” I said, gesturing toward his forearm. “Especially given your build.”

He shrugged. “It’s too late for me. I’m past swag. And honestly, the watch makes me miserable. I can’t decide if it belongs on a strap or a bracelet. I’ve switched so many times I no longer trust my own judgment. The only thing consistent about me is my inconsistency.”

He led me into a bright, tile-heavy kitchen flooded with Southern California light. On the windowsill sat several shortwave radios, arranged among scattered lemons like some improvised altar.

“Not just watches,” I observed. “Radios too.”

He nodded, as if admitting to a second addiction was no longer worth defending.

We sat at the kitchen table eating garlic hummus and rye crackers, drinking dark-roast coffee with soy milk and molasses.

“Welcome,” he said with a tired smile, “to the House of Seiko. My man cave of madness.”

I asked him why an entire community had mobilized to help solve his watch problem.

“I have no idea,” he said. “It’s ridiculous. There are causes that matter. This doesn’t. I’m useless, over the hill, and fully Gollumified.”

The saga began, he explained, at monthly meetups at Mimo’s Jewelry and Watches in Long Beach—friendly gatherings that escalated when he confessed the hobby no longer brought him joy. He wasn’t short on money; he was paralyzed by decision. Every choice felt wrong. The cognitive load became unbearable. He went to bed thinking about watches. He woke up thinking about watches.

“Why not walk away?” I asked.

“Because obsession doesn’t issue exit visas,” he said. “Once you’re in, the riddle feels existential. Solving it felt as urgent as founding a religion. I wanted to crack the code and then preach the gospel of happiness.”

The intervention only made things worse. Camps formed. Seiko purists. Swiss loyalists. Minimalists. Maximalists. Arguments erupted. Then fights. A friend named Manny filmed the altercations. The videos went viral. Suddenly McMahon was a cause célèbre.

“That’s when the watches started arriving in the mail,” he said.

Luxury pieces worth more than his cars. None of them helped. He sold them and donated the money to charity. This, too, became content. More watches arrived. Then robberies. Burglaries. A P.O. box. A manager to process donations and deflect thieves.

Millions eventually went to good causes. The silver lining, as they say.

McMahon stared into his coffee. “I wish I felt redeemed. Mostly I feel disturbed—not just by my obsession, but by how easily the internet turned it into a farce. Sometimes I wonder if it had been anything else—stamps, guitars, fountain pens—would it have played out the same? Or is there something uniquely deranged about watches? Time itself? Father Time? Somehow my fixation feels disrespectful to him.”

He paused, then added, “I have a friend who sold all his luxury watches. He wears a twenty-dollar Casio. Every day he thanks it for keeping him humble. He’s sane. That makes him my hero.”

“You could follow his example,” I suggested. “Salvation is just a Casio away.”

“And sell my divers?” he said flatly. “Not happening.”

“You’d rather be miserable with expensive watches than happy with a cheap one.”

“Exactly. Happiness is irrelevant now.”

I studied him. “I don’t buy it,” I said. “This misery feels performative. A kind of cosplay.”

He nodded slowly. “You’re right. But if I stop playing the miserable man, I have no idea who I’m supposed to be next. And that scares me more than any watch ever could.”