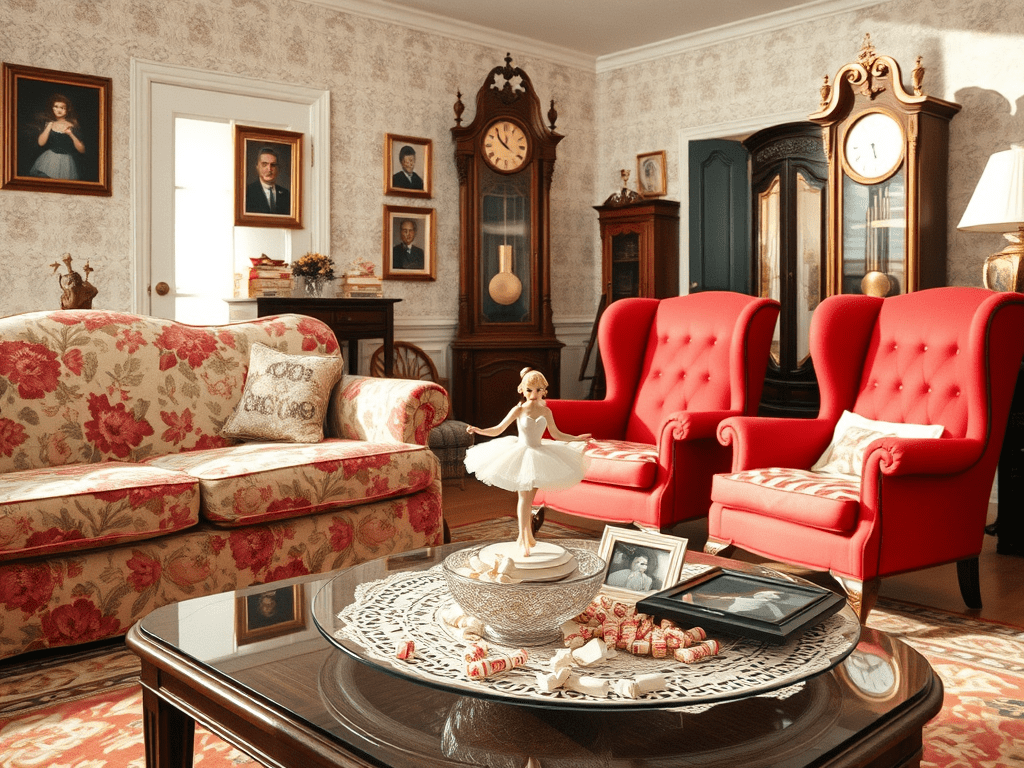

When I was six years old in 1968, I lived for a year with my grandparents in Belmont Shore. One day after school, a distraught neighbor, a 79-year-old widow named Mrs. Davis, said she locked herself out of her house. Could she borrow me to climb through her bedroom window and unlock the front door for her? With my grandmother’s approval, I did just that. I pretended to be a cat burglar, slithered through the ajar window, and walked through her house. With great curiosity, I examined the interior of the living room. The floor was covered with a plush, floral-patterned rug. The centerpiece of the room was a large, floral-patterned couch. It was flanked by two wingback chairs, upholstered in a velvety red fabric. Each chair had a lace doily draped over the backrest. A coffee table with spindly legs sat in front of the couch, its surface crowded with an assortment of knickknacks: a porcelain figurine of a ballerina, a small crystal bowl filled with wrapped candies, and a couple of framed photos. The walls were adorned with family portraits, framed cross-stitch samplers, and a large, oval mirror with a gold frame. A grandfather clock ticked methodically in the background, its pendulum swinging with a steady rhythm that made me feel lost in time. Something came over me. Being alone, I felt possessed with a transgressive spirit, and I lifted the candy jar’s lid and stuffed a butterscotch candy in my pocket before opening the front door for Mrs. Davis. I felt guilty for my act of theft because Mrs. Davis proclaimed me to be her newly-minted hero and handed me a crisp one-dollar bill, which I would later spend on Baby Ruth and Almond Joy Bars. I had difficulty sleeping that night. I worried that Mrs. Davis might feel inclined to take inventory of her candies and discover that one was missing, prompting her to demote me from hero to villain. My career as a thief had come to a quick end. On the other hand, I had a glimpse of what it was like to be a superhero entering houses and saving people in distress. I convinced myself that my career as Superman was just beginning.

Author: Jeffrey McMahon

-

I Had to Choose to Either be a Thief Or Superman

-

DON’T GET TRAPPED IN A FLINTSTONES BACKGROUND LOOP

In Arnold: The Education of a Bodybuilder, Arnold Schwarzenegger observes that bodybuilding is not merely a means toward self-improvement of the body. It opens other doors as well in business and other enterprises. I found that Arnold was right: My teenage years of toiling in the gym and amassing muscles finally paid off in 1979 when, at the tender age of seventeen, I landed the coveted position of bouncer at Maverick’s Disco in San Ramon, California. I was rolling in dough, earning a whopping ten cents over the minimum wage at three dollars an hour, while enjoying the luxurious perks of free soft drinks and peanuts. My nights were spent amidst a sea of polyester pantsuits and hairdos so heavily sprayed they constituted a legitimate fire hazard. I thought I had hit the jackpot, killing two birds with one stone: raking in the cash while strolling around the teenage disco, flexing my lats, and mingling with an endless parade of beautiful women. However, my dreams of disco glory were dashed when I encountered a cruel concept I’d later learn about in my college Abnormal Psychology class: the anhedonic response. This phenomenon numbs the brain to repeated stimulation, leading to a state of anhedonia, where happiness and pleasure are but distant memories. Thinking about anhedonia took me back to the moment when I stopped enjoying my beloved cartoon, The Flintstones. One day, as Fred and Barney drove their caveman car down the highway, I noticed the background—a series of trees, boulders, and buildings—repeating over and over. This revelation shattered the show’s illusion of reality, much like seeing how the sausage is made. Watching The Flintstones was never the same again. Maverick’s Disco was my Flintstones moment. Night after night, I watched customers flood the club with faces lit up with high expectations of excitement, glamour, and romantic connections. By closing time, those same faces were glazed over, tired, and disappointed. Yet, like clockwork, they returned the next weekend, ready to repeat the cycle. My life at the disco had become the monotonous wraparound background of The Flintstones. It was a sign that I needed to quit. Like Arnold Schwarzenegger, I needed to break out of a limited situation, spread my wings, and fly.

-

WHEN WATCHING PIE BAKING CONTESTS ELEVATES THE SOUL

Many moons ago, my wife and I watched the 2006 HBO documentary Thin, which chronicles the tragic existence of girls in a Florida rehab clinic for eating disorders. These poor souls were ensnared in a vicious cycle of depression, self-loathing, and lies, their recovery rates abysmally low and fatality rates tragically high. After this emotional gut-punch, we desperately needed a palate cleanser, so we turned to a pie-baking contest featuring Midwestern women in Christmas sweaters, lovingly toiling over pie crusts. These wholesome warriors of the kitchen were a stark contrast to the aforementioned sufferers. It dawned on me that pie baking is the antithesis of anorexia—a condition of solipsism where one disappears into the self, whereas pie baking is a testament to community, love, and selfless devotion to butter and flour.

Imagine, if you will, a world where the kitchen isn’t just a hub of culinary creation but a sacred temple of love, where pie-baking is the highest form of devotion. In this sanctified realm, every Midwestern woman in a Christmas sweater is a culinary high priestess, her rolling pin a scepter of affection, her pie crust a canvas for heartfelt artistry. The Pie Baking Contest is an epic battleground where these valiant women gather, their aprons fluttering like superhero capes, ready to channel pure, unadulterated love into their pies. The stakes are absurdly high, the competition fierce, but the atmosphere? Pure camaraderie and joy.

Here, pie baking is not just a quaint pastime; it’s an epic saga of love, community, and unyielding devotion. These heroines approach their craft with the precision of neurosurgeons and the passion of Renaissance artists. Flour fills the air like enchanted snow, butter is blended into dough with the deftness of a master illusionist, and apples are peeled and sliced with the ferocity of a seasoned samurai. Each pie is a labor of love, a tangible expression of their deepest affections. As they sweat and toil over their creations, the kitchen morphs into a bustling hub of warmth and connection.

Baking pies, slinging spaghetti and garlic bread, or whipping up a dish of hot and sour Tom Yum Goong soup demands a healthy soul, one that’s plugged into the matrix of family and community. We therefore don’t journey solo but soar with a merry band of culinary adventurers, armed with spatulas and mixing bowls, ready to conquer the next great feast. So, skip the guilt and embrace the butter—life’s too short for bland food and empty kitchens.

-

EATING THE UNCLE NORMAN WAY

Every morning during my teenage years, I’d stagger out of bed and make my daily plea to the heavens: “God, please grant me the confidence and self-assuredness to ask a woman on a date without suffering from a full-blown cerebral explosion.” And every morning, God’s response was as subtle as a sledgehammer to the forehead: “You’re essentially a walking emotional landfill, a neurotic mess doomed to wander the planet bereft of charm, romantic grace, and any semblance of healthy relationships. Get used to it, buddy.” And thus commenced my legendary odyssey in the land of perpetual non-dating.

This was not the grand design I had envisioned. No, the blueprint was to be a suave bachelor, just like my childhood idol, Uncle Norman from The Courtship of Eddie’s Father. At the ripe age of eight, I watched in awe as Uncle Norman demonstrated his revolutionary kitchen hack: why bother with dishes when you can devour an entire head of lettuce while standing over the sink? He proclaimed, “This way, you avoid cleanup, dishes, and the pesky inconvenience of sitting at a table.” In that glorious moment, I was struck with a revelation so profound it reshaped my entire existence. The Uncle Norman Method, as I would grandiosely dub it, became my life’s guiding principle, my personal beacon of satisfaction, and the defining factor of my existence for decades.

Channeling my inner Uncle Norman, I envisioned a life of unparalleled convenience. My bed would be perpetually unmade because who needs sheets when you have a trusty sleeping bag? I’d never waste time watering plants—plastic ones were far superior. Cooking? Please. Cereal, toast, bananas, and yogurt would sustain me in perpetuity. My job would be conveniently located within a five-mile radius of my house, and my romantic escapades would be strictly zip code-based. Laundry? My washing machine’s drum would double as my hamper, and I’d simply press Start when it reached capacity. Fashion coordination? Not a concern, as all my clothes would be in sleek, omnipresent black. My linen closet would be repurposed to stash protein bars, because who needs linens anyway?

I’d execute my grocery shopping like a stealthy ninja, hitting Trader Joe’s at the crack of dawn to dodge crowds, while avoiding those colossal supermarkets that felt like traversing a grid of football fields.

Embracing the Uncle Norman Way wasn’t just a new approach to dining; it was a radical overhaul of my entire lifestyle. The world would bow before the sheer efficiency and unadulterated convenience of my new existence, and I would remain eternally satisfied, basking in the glory of my splendidly uncomplicated life.

Of course, it didn’t take long for my delusion to expand into a literary empire—or at least, that was the plan. The world, I was convinced, desperately needed The Uncle Norman Way, my magnum opus on streamlining life’s most tedious inconveniences. It would be part manifesto, part self-help guide, and part fever dream of a man who had spent far too much time contemplating the finer points of lettuce consumption over a sink. Each chapter would tackle a crucial element of existence, from the philosophy of single-pot cooking (aka, eating directly from the saucepan) to the art of strategic sock re-wearing to extend laundry cycles. I even envisioned a deluxe edition featuring tear-out coupons for discounted plastic plants, a fold-out map of the most efficient grocery store layouts, and, for true devotees, a companion workbook to track their progress toward the ultimate goal: Maximum Laziness with Minimum Effort™.

Naturally, I imagined its meteoric rise to cultural dominance. Talk show hosts would marvel at my ingenuity, college professors would weave my wisdom into philosophy courses, and minimalists would declare me their messiah. Young bachelors, overwhelmed by the burden of societal expectations, would turn to my book in their darkest hour, finding solace in the knowledge that they, too, could abandon the tyranny of dishware and lean fully into sink-based eating. The revolution would be televised, one head of lettuce at a time.

-

The Demise of Danish Go-Rounds Will Never Be Forgiven

Introduced by Kellogg’s in 1968, Danish Go-Rounds were like the golden fleece of breakfast pastries. Imagine Pop-Tarts, but with the sophistication of a five-star dessert. The brown sugar-cinnamon Danish Go-Rounds were so addictive, they made crack look like a mere curiosity. At the ungodly hour of 2 a.m., millions of Americans would wake up in cold sweats, their cravings driving them to frenzied searches for the Nectar of the Gods—only to find their precious pastries had vanished into thin air. Then, in a move so baffling it felt like a conspiracy against breakfast enthusiasts everywhere, Kellogg’s pulled the plug on Danish Go-Rounds in the mid-seventies. They kept the Pop-Tarts, those cardboard-like impostors that tasted like they were designed by a committee of flavorless robots. The heartbreak was palpable. It was as if a divine bakery had been shut down and replaced with a factory that churned out glorified toaster insulation. The eradication of Danish Go-Rounds is now remembered as one of the most colossal institutional blunders in history—up there with the fall of Rome and the invention of the Rubik’s Cube. The void they left was so immense, it bored a gaping chasm in my soul. My heart, once full of pastry-filled joy, now echoed with the hollow sound of Pop-Tarts’ lifeless crunch. While Danish Go-Rounds faded into the annals of breakfast history, Pop-Tarts flourished like a tasteless, mass-produced phoenix. This shift symbolized the erosion of artisanal craftsmanship and the triumph of consumer complacency. It heralded the rise of such culinary horrors as Imperial Margarine, Tang, Space Food Sticks, Boone’s Farm Apple Wine, and SlimFast—products so tragic they make a TV dinner look like a gourmet feast. The Gastronomic Time Traveler had to bear witness to this disheartening transition, seeing the demise of pastries that were practically food royalty. In their place, we got a parade of processed atrocities that made the culinary landscape look like a dystopian nightmare. So there I was, left to mourn the loss of Danish Go-Rounds, savoring the bitter taste of what once was, while choking down the unworthy replacements that flooded the market. It was a breakfast apocalypse, and I was living in its soggy aftermath.

-

WALTER CRONKITE AND FRANK SINATRA WERE THE TRUSTED PROPHETS OF MY YOUTH

At four years old, a pocket-sized philosopher in footie pajamas, I’d often find myself stationed in the living room like a tiny sentinel, transfixed by the glow of our hulking television set. The air was thick with the comforting aroma of my mother’s lasagna or spaghetti, a scent that promised warmth and stability, while my father and I tuned in to the evening sermon of Walter Cronkite. Cronkite, that square-jawed oracle of truth, delivered the news with the gravitas of a benevolent yet exhausted deity. His voice—measured, slightly weary—wrapped around the day’s events like a woolen blanket, equal parts reassurance and obligation, as necessary as a nightly dose of cod liver oil or a reluctant gulp of Ovaltine.

But Cronkite, for all his journalistic divinity, did not hold the title of Supreme Voice in our household. That honor belonged to Frank Sinatra, whose velvet baritone floated from our Fischer Hi-Fi console stereo with the omnipresence of a household deity. Sinatra wasn’t merely a singer—he was a prophet, a sage in a sharp suit, the Cronkite of melody, issuing dispatches on love, loss, and longing with a conviction that made it clear: this was the stuff of life. His voice had the eerie authority of a celestial news anchor, forewarning me of adulthood’s looming weather patterns—storms of responsibility, gales of regret, hurricanes of heartbreak.

At an age when my greatest concern should have been whether I got the last Nilla Wafer, I found myself drowning in premature nostalgia, gripped by the weight of Sinatra’s melancholic musings. “It Was a Very Good Year” hit my preschool psyche like an existential anvil—suddenly, I was an ancient soul trapped in a toddler’s body, debating whether to pair my Triscuits with a port wine cheddar spread or just give in and sip on some prune juice like a man resigned to his fate. Sinatra had me feeling so prematurely adult, I half-expected a cigar to materialize in my hand or to receive a personal invitation to an exclusive stockholder’s meeting.

I wasn’t just waiting for dinner. I was reckoning with life’s grand metaphysical dilemmas, wrestling with the realization that the world was vast, unknowable, and, worst of all, drenched in longing. And yet, as I sat there, absorbing the gospel of Ol’ Blue Eyes, I couldn’t help but suspect that Sinatra had the answers—the ones I wouldn’t fully understand until I was old enough to toast my regrets with a stiff drink and a knowing smirk.

-

LARRY SANDERS: WHEN YOUR ONLY MEASURE OF SELF-WORTH IS THE NIELSEN RATING

The Larry Sanders Show is, at its core, a study in impoverishment—not financial, mind you, but emotional, existential, and spiritual. It’s a bleak yet hilarious portrait of men so starved for validation that their only measure of self-worth is the Nielsen rating. Without it, they might as well not exist. The three principals—Larry Sanders, Hank Kingsley, and Artie the producer—are all flailing in different shades of desperation, their egos so fragile they make pre-teen TikTok influencers look well-adjusted.

What’s astonishing is that these men are emotional dumpster fires in a pre-social media era. Had they been forced to navigate Instagram, they’d have suffered full mental collapse long before season six. Larry, in particular, embodies this fragile insecurity perfectly: there he is, night after night, lying in bed with some beautiful woman, but his true lover is the TV screen, where he watches his own performance with a mix of self-loathing and obsessive scrutiny. His actual partner—flesh, blood, and pleading for his attention—might as well be a houseplant.

Hank Kingsley, meanwhile, is a slow-motion trainwreck of envy and delusion. He loathes Larry with the fire of a thousand suns, seeing his role as sidekick as a cosmic insult to a man of his alleged grandeur. His existence is a never-ending, one-man King Lear, with far more Rogaine and far less dignity.

Then there’s Artie, the producer, the closest thing the show has to a functional adult. He wrangles chaos with a cigarette in one hand and a whiskey in the other, managing to keep the circus running even as its ringleader is in freefall. But Artie, too, is an emotional casualty. He can juggle Larry’s neuroses and Hank’s tantrums with military precision, yet his own life is a shipwreck, his ability to maintain order confined strictly to the world of late-night television.

Yet for all its cynicism, the show doesn’t just leave us gawking at these wrecked souls—it makes us care. We want them to wake up, to claw their way out of their vanity-driven stupor, to abandon the mirage of celebrity and seek something real. But they won’t. They can’t. They are too drunk on the high of public approval, too lost in the spectacle of show business, too incapable of self-awareness to change course. And so we watch them burn out in real time, laughing through the tragedy, absorbing its lessons like a cautionary tale wrapped in razor-sharp wit.

In the end, The Larry Sanders Show is the perfect showbiz fable: hilarious, cutting, deeply sad, and just self-aware enough to let us laugh at the madness while secretly wondering if we, too, are addicted to the same empty validation.

-

NOT THE GREATEST AMERICAN HERO

When I was a nineteen-year-old bodybuilder in Northern California, I stumbled into a gig at UPS, where they transformed the likes of me into over-caffeinated parcel gladiators. Picture this: UPS, the coliseum of cardboard where bubble wrap is revered like a deity. My mission? To load 1,200 boxes an hour, stacking them into trailer walls so precise you’d think I was defending a Tetris championship title. Five nights a week, from eleven p.m. to three a.m., I morphed into a nocturnal legend of the loading dock. Unintentionally, I shed ten pounds and saw my muscles morph into something straight out of a comic book—like the ones where the hero’s biceps could bench-press a car.

I had a chance to redeem myself from the embarrassment of two previous bodybuilding fiascos. At sixteen, I competed in the Mr. Teenage Golden State in Sacramento, appearing as smooth as a marble statue without the necessary cuts. I repeated the folly a year later at the Mr. Teenage California in San Jose. I refused to let my early bodybuilding career be tarnished by these debacles. With a major competition looming, I noticed my cuts sharpening from the relentless cardio at UPS. Redemption seemed not only possible but inevitable.

Naturally, I did what any self-respecting bodybuilder would do: I slashed my carbs to near starvation levels and set my sights on the 1981 Mr. Teenage San Francisco contest at Mission High School. My physique transformed into a sculpted masterpiece—180 pounds of perfectly bronzed beefcake. The downside? My clothes draped off me like a sad, deflated costume. Cue an emergency shopping trip to a Pleasanton mall, where I found myself in a fitting room that felt like a shrine to Joey Scarbury’s “Theme from The Greatest American Hero,” the ultimate heroic anthem of 1981.

As I tried on pants behind a curtain so flimsy it could’ve been mistaken for a fogged-up windshield, I overheard two young women employees outside arguing about which one should ask me out. Their voices escalated, each vying for the honor of basking in my bronzed splendor. As I slid a tanned, shaved calf through a pants leg, I pictured the cute young women outside my dressing room engaged in a WWE smackdown right there on the store floor, complete with body slams and flying elbows, all for a dinner date with me. This was it—the ultimate validation of my sweat-drenched hours in the gym. And what did I do? I froze like a deer in headlights, donning an aloof expression so potent it was like tossing a wet blanket on a fireworks show. They scattered, muttering about my stuck-up demeanor, while I stood there in my Calvin Kleins, paralyzed by the attention I had so craved.

For a brief, shining moment—from my mid-teens to my early twenties—I possessed the kind of looks that could make a Cosmopolitan “Bachelor of the Month” seem like the “Before” picture in a self-help book. But my personality? Stuck in the same developmental phase as a slab of walking protein powder with the social finesse of a half-melted wax figure.

I had sculpted the body of a Greek god but inhabited it with the poise of a toddler wearing his dad’s shoes. In this regrettable state, I found that dozens of attractive women threw themselves at me, and I responded with the enthusiasm of a tax auditor on Xanax. Look past the Herculean exterior, and you’d find a hollow shell—a construction site abandoned mid-project, complete with rusted scaffolding and a sign that said, “Sorry, we’re closed.”

-

TRAINING WITH THE WRESTLING STARS ON TV FELT LIKE A FEVER DREAM

Training at Walt’s Gym in the mid-70s wasn’t just about lifting weights—it was an unfiltered, sweat-drenched fever dream where my adolescent reality collided head first with the muscle-bound mythology of Big Time Wrestling. For two years in the early 70s, I had religiously watched Big Time Wrestling on Channel 44, glued to my TV screen, captivated by the larger-than-life personas of Pat Patterson, Rocky Johnson, Kinji Shibuya, Pedro Morales, and Hector Cruz. Then, as if fate had decided to prank me, a few years later I found myself sharing dumbbells with these very same legends as a clueless, starstruck thirteen-year-old Olympic weightlifter.

At first, it was thrilling—until my big mouth turned the dream into a farce. Despite carrying a respectable amount of muscle for my age, I had the survival instincts of a gazelle on tranquilizers. Take, for example, the time I was doing cable lat rows next to Hector Cruz, a man whose forehead looked like a war zone of scar tissue. In a stunning act of idiocy, I casually mentioned that I’d heard rumors that wrestling might, gasp, be fake.

Cruz, mid-rep, snapped his head toward me with the kind of stare that could curdle milk. “Look at these scars on my face! Do they look fake to you?” he growled, his voice carrying the weight of a man who had spent years being thrown into turnbuckles for a living. I nodded solemnly, silently wondering if plastic surgery had advanced to the point of replicating decades of chair shots and steel cage matches.

Then there was the Great Towel Incident, in which my ignorance of gym etiquette nearly got me suplexed into another dimension. Spotting a towel draped over the calf raise machine, I assumed—like a naive idiot—that it was communal property, perfect for mopping my sweat-drenched forehead. A fraction of a second later, a mountain of muscle erupted from a nearby bench press, veins bulging, eyes locked onto me like a heat-seeking missile.

“That YOUR towel, kid?” he snarled, his biceps twitching in a way that suggested he resolved most disputes with his fists. Before I could sputter out an excuse, he made it abundantly clear that swiping another man’s gym towel was the equivalent of stealing his car, his wife, and his dog in one fell swoop. Lesson learned: gym towels are sacred artifacts, and touching one without permission is an offense punishable by immediate death or, worse, public humiliation.

But the crowning jewel of my social missteps at Walt’s Gym was my commitment to primal, theatrical grunting—a misguided attempt to add some dramatic flair to my workouts. I thought my earth-shaking screams made me sound like a warrior; in reality, they made me sound like someone having an exorcism mid-bench press.

One day, my sound effects finally pushed a competitive bodybuilder—who looked like a bronze statue of vengeance—to his breaking point. He pulled me aside, his stare filled with enough hostility to burn a hole through my skull. “Kid,” he said, his voice dangerously low, “if you don’t cut the screaming, someone’s going to shut you up permanently. And trust me, they’ll get a standing ovation for it.”

That was my wake-up call. Surviving Walt’s Gym wasn’t just about lifting heavy—it was about mastering the unspoken social codes that separated the seasoned warriors from the clueless rookies. The iron jungle had rules, and I was learning them one near-death experience at a time.

-

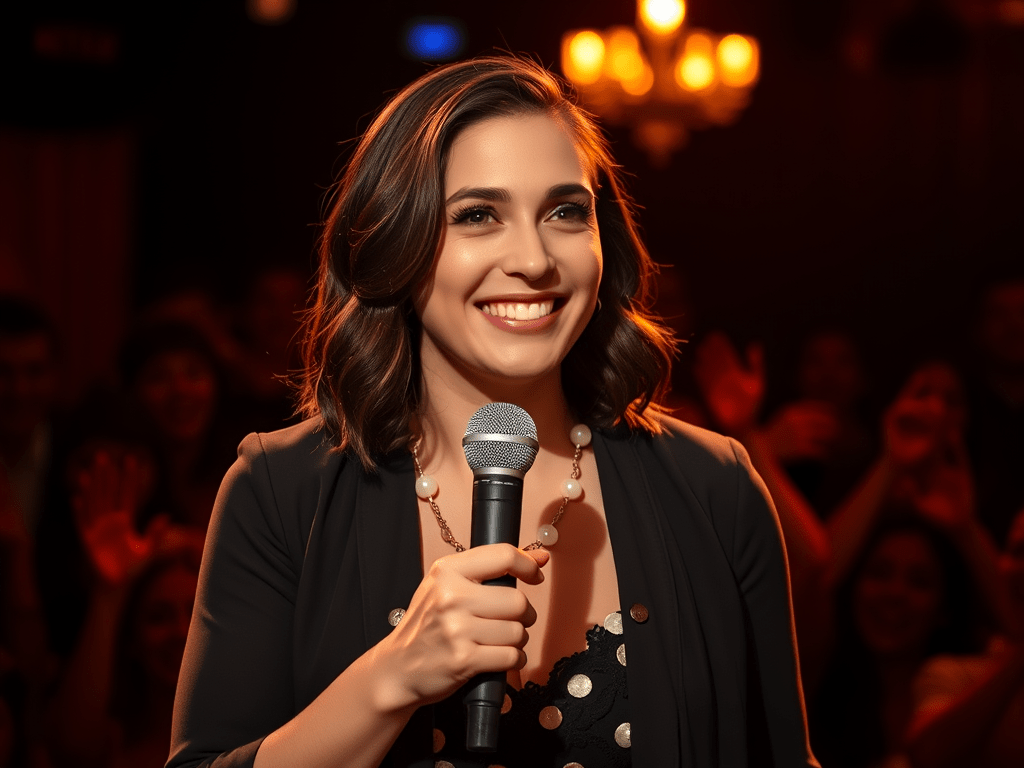

LIZA TREYGER BELONGS ON STAGE

In her Netflix stand-up special Night Owl, Liza Treyger unleashes an hour of manic brilliance, slicing through life’s absurdities with the gleeful energy of a woman who has long accepted—if not fully embraced—her own chaos. Smiling, effervescent, and naturally sarcastic, she delivers a rapid-fire confessional that feels less like a polished comedy routine and more like an open mic night inside her own hyperactive brain.

She tells us she was born near the Chernobyl meltdown and now has a lifelong thyroid condition, that her attention span has been obliterated by her smartphone, that she’s forfeited all privacy in exchange for algorithm-curated animal videos, and that her Russian father has an uncanny ability to humiliate her by showing up to formal events in wildly inappropriate T-shirts. She doubts she has the temperament for marriage, children, or any relationship that lasts longer than a Bravo reality show season. She adores living in New York, even though she’s been mugged three times. She got an oversized butterfly tattoo—not because she wanted one, but because she was avoiding the soul-crushing task of changing her printer’s toner cartridge. She’s hungry for applause about losing forty pounds, even though she’s gained it all back. She’s openly critical of her therapist for being judgmental, yet she happily judges everyone around her. She has an encyclopedic knowledge of The Real Housewives franchise, capable of reciting random episodes in disturbingly granular detail. And, above all, she might be a bit of a misfit—too addicted to salacious gossip to maintain deep, lasting friendships.

Treyger is intimidatingly sharp. I like to think I have a respectable level of intelligence, but I’m fairly certain she would find me basic and tedious—a conclusion I’ve already reached about myself, so no harm done. Watching Night Owl felt like a vacation from my own dullness, a thrilling rollercoaster ride through the mind of someone far wittier, sharper, and quicker than I could ever hope to be.

For someone who claims to be a misfit, she fits perfectly on a comedy stage. The very qualities that alienate her in real life—her inability to stop talking, her obsession with gossip, her unfiltered, razor-sharp takes—are her greatest gifts in front of an audience. I’d listen to her anywhere.