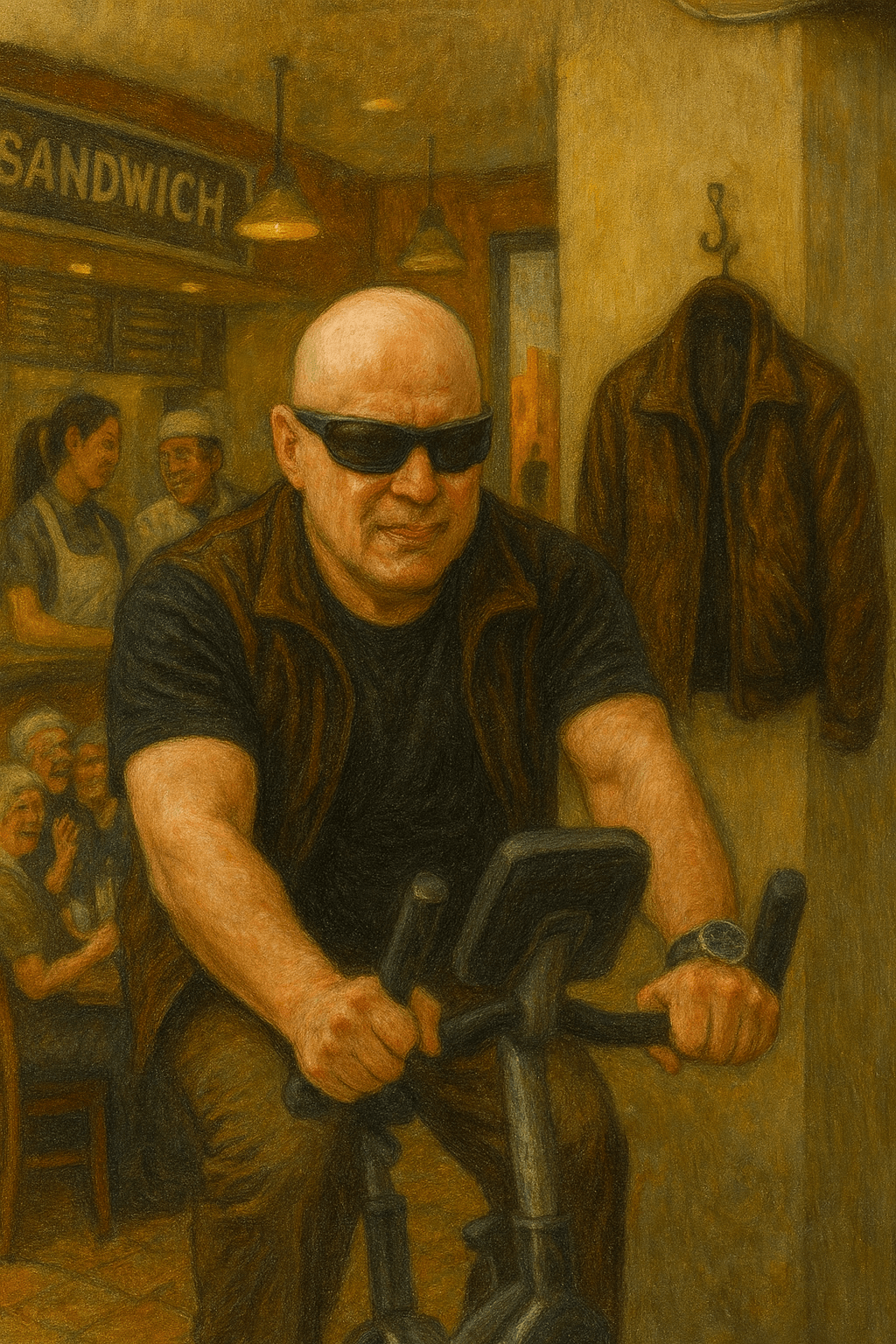

Eighteen months ago, when I tore my rotator cuff, I made the first of several reluctant concessions to age and anatomy. My one-hour kettlebell workouts dropped from five days a week to three. In their place, I resurrected the Schwinn Airdyne—a machine I trust because it does not care about my feelings. I rode it for 50 to 60 minutes, three or four days a week, and in the early going I had to work hard to burn 600 calories in 54 minutes. Progress came slowly, then grudgingly, then reliably. Soon it took only 48 minutes to hit 600. In the last month, I was regularly landing around 700 calories in 56 minutes.

Then came yesterday.

I burned 825 calories in 61 minutes. Nearly 800 calories per hour. That’s not training; that’s an episode. That’s one of those rare days when the body cooperates, the mind goes feral, and the machine quietly accepts its role as accomplice.

But we need to talk about today.

Today, I slogged. I crawled. I negotiated with myself minute by minute. I finished with a humiliating 500 calories in 56 minutes—a meager 535 calories per hour. That’s roughly a third less output than yesterday. As someone who motivates himself through numbers, benchmarks, and internal scorekeeping, this wasn’t just disappointing. It was existential.

Gamification cuts both ways.

There were, however, mitigating factors. Last night I spent three hours locked in mortal combat with an old toilet seat, sweating through three T-shirts while attempting to remove plastic wing nuts that had apparently fused with time itself. During this campaign, I punched myself in the face with a pair of pliers, opening a respectable gash across my nose. I woke up sore in places no exercise program claims credit for.

I suspected today’s ride would be compromised. I just didn’t anticipate how compromised. Working out this morning after last night’s ordeal felt like an NFL linebacker playing Monday Night Football and then being asked to suit up again on Thursday night. The schedule was punitive. What I needed was rest—another full day of it.

To console myself, I did what any reasonable person would do: I cooked the books. Surely that three-hour ordeal burned at least 400 calories. Add that to today’s 500 on the Airdyne and—there it is—900 calories. A full 200 calories over my goal.

Victory.

The ledger balances. My bragging rights are being processed. All that remains is a warm bathtub and the quiet satisfaction of knowing that even on an off day, I still managed to win the argument with myself.