I wanted a Tecsun in my bedroom—not some soulless streaming device, but a real radio, one with warmth, charm, and that inexplicable magic that only live broadcasts can offer. The idea was simple: a companion for afternoon naps and late-night reading sessions set to the soothing sounds of classical or jazz. After all, what better antidote to our algorithm-driven existence than the analog embrace of a good radio?

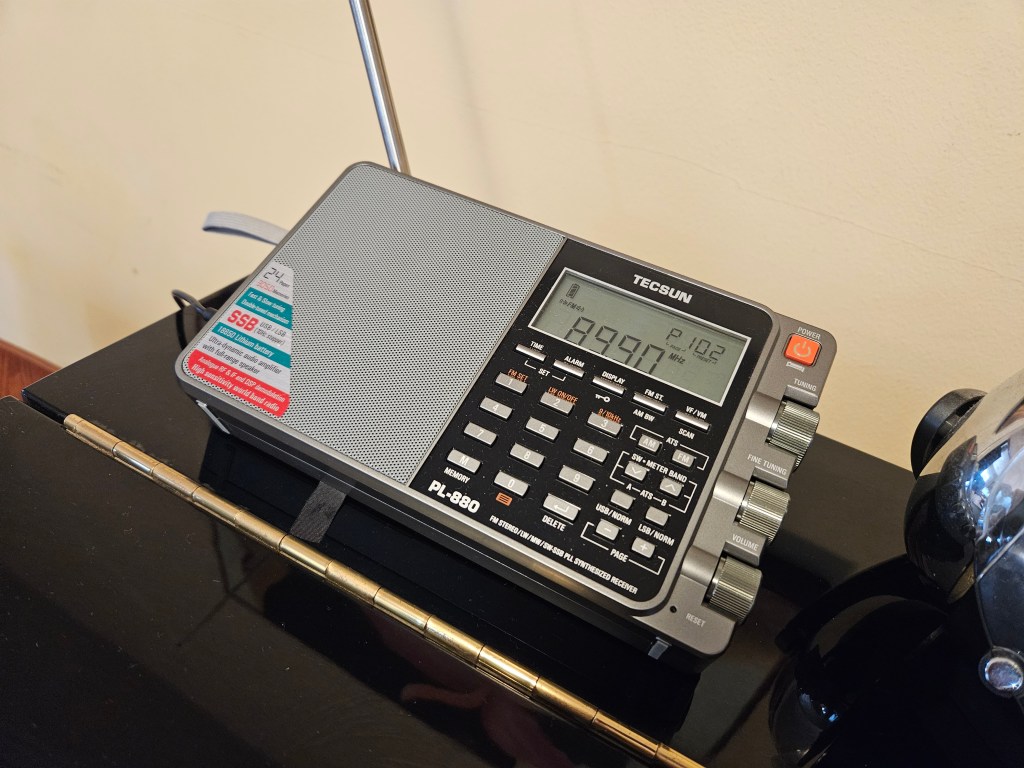

Back in my radio-obsessed heyday around 2008, I foolishly sold my beloved Tecsun PL-660. Call it hubris, call it a lapse in judgment, but I’ve regretted it ever since. To atone, I snagged a used PL-660 for the kitchen and, for my bedroom sanctuary, opted for a Tecsun PL-880—a model lauded as a minor deity among radios.

Now, let’s talk about my brief but painful dalliance with the PL-990. I ordered it from the reputable Anon-Co, expecting greatness, only to be greeted by an AM band as dead as a doorknob. Heartbreaking. Back it went, and in its place came the PL-880, slightly used but fully tested. And let me tell you, the speaker on the 880 is a revelation—warmer and more inviting than the 990’s. It’s like stepping into a cozy jazz club versus a sterile concert hall.

The 880 arrived ready for action, with AM and FM defaults already set to North American standards—no fiddling required. On “DX” mode, the AM band delivers stunning clarity with zero floor noise or interference. It’s a joy to listen to, unlike 95% of the radios cluttering the market that barely rise above the status of glorified paperweights. FM performance is similarly impressive, though 89.3 gave me a little attitude when placed too close to the wall. A quick relocation to the bed or a spot away from the wall solved that, but the rest of the FM dial? Flawless. KCRW 89.9, in particular, comes through like it’s broadcasting from my nightstand, even while the battery charges.

Speaking of AM, charging compromises its pristine reception, so I stick to battery power for those late-night AM sessions. Setting presets and navigating pages took a bit of patience—about 15 minutes of trial and error—but the interface is intuitive enough that even if you mess it up, direct entry is a breeze.

In short, the PL-880 does exactly what I hoped it would: it fills my room with rich, crystal-clear sound, providing a listening experience that feels both luxurious and intimate. Sure, the PL-990 looks great and has fantastic build quality, but for my purposes, the 880 checks every box at a fraction of the cost. Why throw extra cash at a feature set I don’t need?

Here’s the thing about being radio-obsessed: a radio isn’t just a gadget. It’s a companion, a quiet presence that connects you to a wider world while anchoring you in your own space. The PL-880 is just that—a welcome friend who’s already earned its place in my home.