I arrived at the Palos Verdes trails just before ten, and the heat was already doing its best impression of a convection oven. The mountainous trails, baking under the relentless sun, were separated from the street by a chain-link fence that looked like it had given up on life years ago. Inside the confines of this makeshift pen, several dozen goats were having the time of their lives munching on dry grass as if it were the most gourmet hay in existence. Their faces were a mix of innocent curiosity and that absurd kind of adorableness that makes you momentarily consider swearing off lamb chops forever. I made a mental note to “consider veganism” again, a notion I promptly squashed with vivid memories of my O-positive blood rejoicing every time I indulged in a perfectly seared ribeye. Hello, goats—you’re safe because it looks like I’ll stick with beef.

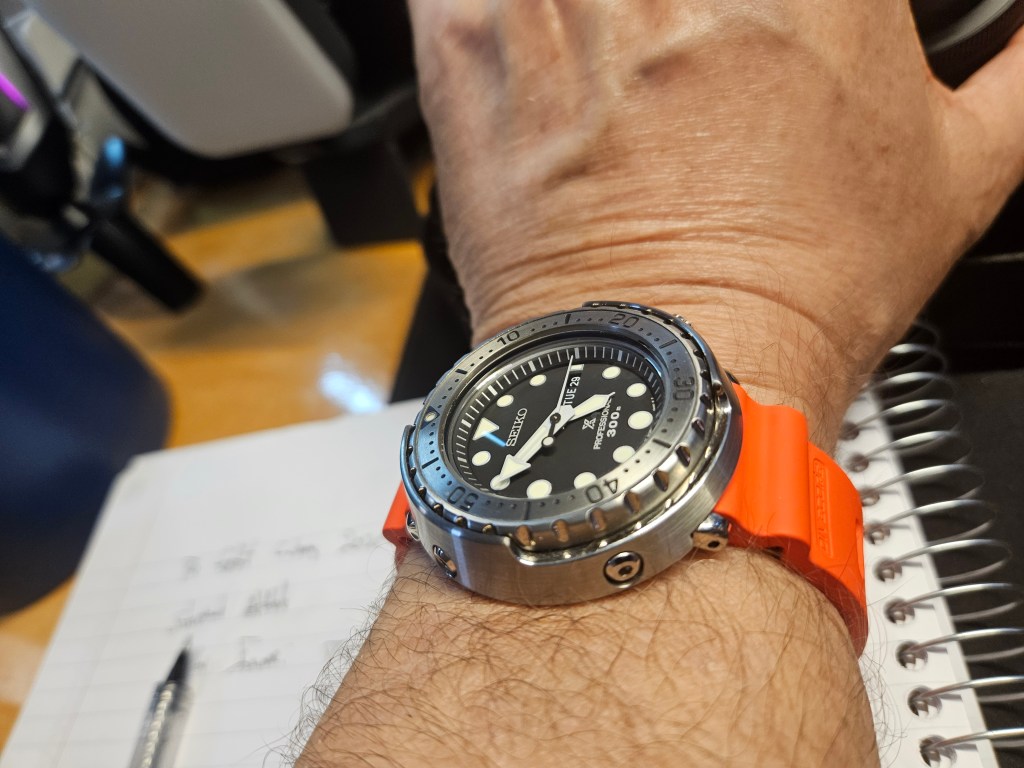

By the goats, a white tent had been pitched like some sort of mirage, and under it, a circle of chairs was arranged with the precision of a cult meeting—or worse, a corporate team-building exercise. The man who had the audacity to call himself the Abbot greeted me with a grin that suggested we were about to embark on a day of carefree yachting rather than whatever bizarre ritual he had planned. Forget the flowing robes and monastic aura—I was greeted by a fitness model straight out of an overenthusiastic health magazine. Neatly pressed cargo shorts hugged his cycler’s thighs like they had been tailored for the occasion, and his olive T-shirt clung to a body sculpted by what could only be an unholy alliance with a CrossFit gym.

A cross-body sling bag was slung over one of his thin yet annoyingly muscular arms, which were covered in veins that seemed to be competing in an under-skin relay race. His jawline could have cut glass, and his neatly sculpted silver hair made him look like he’d stepped out of an L.L.Bean catalog. But it was his eyes that really got me—blazing blue orbs that looked like they belonged on the figurehead of a Viking ship, ready to plunder and pillage.

“Graham, come join us,” he said with the kind of enthusiasm that suggested we were minutes away from sipping mimosas on a luxury yacht. “We are just moments away from the interrogation.” The way he said “interrogation” made it sound like a delightful little jaunt instead of, you know, something that involved possible torture or at least a really awkward group discussion.

The most striking thing about the Abbot wasn’t his absurdly chiseled jawline or his militant posture; it was the overwhelming stench of lavender and rose water that assaulted my senses the moment I got within a hundred yards of him. This man hadn’t just splashed himself with these fragrances—he’d practically marinated in them. It was as if he’d decided to pickle himself in a floral potpourri so potent that it probably had bees tailing him for miles. I half-expected to find petals stuck to his skin.

As I reluctantly made my way under the tent, I was greeted by the sight of six people slumped in those classic, soul-crushing folding chairs that practically shriek, “We’re only here for the free food.” These weren’t just any ordinary folks. No, these were the future friends, foes, and backstabbers who would weave themselves into the disaster that would soon be my life—though at that moment, they all just looked like they were wondering when the punchline of this bizarre setup was going to drop. Spoiler: It never did.

Behind them, a table stood like a beacon of false hope. A giant pitcher of cucumber water glistened in the sunlight, promising hydration that would do nothing to wash away the impending madness. But what truly caught my eye was the stack of cakes beside it. They looked innocent enough, these little golden blocks, but I would soon discover that they were the Abbot’s specialty—cornbread cakes made with applesauce, honey, and some vanilla-flavored soy protein powder that tasted suspiciously delicious. These cakes weren’t just a snack; they were a trap, a gateway drug that would soon have me spiraling into a carb-induced dependency I hadn’t seen coming. But let’s not jump ahead—there’s plenty of time to explore how these seemingly harmless cakes would drag me into the Abbot’s world of sweet-smelling insanity.

For now, let’s just say that in that moment, my biggest mistake wasn’t walking into the tent—it was deciding to stay. But hey, who could resist free “light refreshments”?

With one arm draped around my back like a used car salesman about to seal a shady deal, the Abbot steered me toward the motley crew assembled under the tent. He flashed a benevolent smile, the kind that makes you wonder if he’s about to offer you enlightenment or swindle you into buying a timeshare in Cancun. “My friends,” he announced with all the pomp of a second-rate cult leader, “Graham has graced us with his presence. He is a college writing instructor with many gifts, though I’ll let him elaborate on those special talents later.” His smile suggested that whatever “gifts” I possessed were about to be squeezed out of me like juice from a lemon.

He pointed at each member of the ragtag group, starting with Abigail, a woman in her early fifties who looked like she’d been carved out of a block of pale, pasty clay by a very angry sculptor. Her squat frame and monkish haircut didn’t do her any favors, but she smiled with the kind of pride usually reserved for people who’ve just completed their first marathon, despite the fact that she hailed from Gorman—a town so small it might as well not exist—where she’d spent her youth dodging aggressive chickens on her parents’ farm. Abigail proudly raised three fingers, showcasing them as if they were battle scars, and regaled us with tales of surviving on a teeth-rotting diet of PayDay bars and orange Fanta until she discovered The Abbot’s life-altering cornbread cakes. You’d think she’d found the Holy Grail, but instead, it was just some glorified baked goods.

Next up was Larry, a man in his late forties who had apparently modeled his look on a 1970s mafia reject. His long, slicked-back hair and tinted sunglasses made him look like he was auditioning for the role of “Skeevy Casino Manager” in an off-off-Broadway production. Dressed in black jeans and a too-tight white T-shirt that clung to his muscular upper body like a bad decision, he had the kind of physique that screamed “I skipped leg day,” with spindly legs that looked like they’d snap under the weight of his overly pumped chest. Larry had once been a professional gambler until every casino in the area wisely decided he was bad for business. Now, he managed an upscale Mexican restaurant at Del Amo Mall—a stone’s throw from my house—where he spent his days chain-drinking Red Bull and dreaming of the good old days. “I was probably killing myself drinking all those chemicals and caffeine,” he said, “but thanks to the Abbot and his cornbread cakes, I’m learning the true path.”

Larry’s brother Stinky, who looked like he’d just crawled out of the primordial ooze, sat next to him. With shaggy blond hair, deep pockmarks, and a forehead that could have been used as a Neanderthal fossil exhibit, Stinky was the kind of guy who seemed to wear his heartbreak on his sleeve—and his face. In his late thirties and still stuck in a dead-end job at a Costco warehouse, he was the embodiment of a bad country song. His high school sweetheart had skipped town with his engagement ring and now worked as a “hostess” at various questionable establishments in Miami. “Self-pity is my addiction,” he confessed, as if he’d just admitted to a crippling heroin habit. But don’t worry—the Abbot was going to give him a “second shot at life,” presumably with a side of cornbread cakes.

Maurice shuffled forward, a short, wiry guy with a dark complexion. Looking much younger than his age of forty, his kid’s face was set in a permanent grimace, like he’d just stepped in something nasty and couldn’t shake the stench. He was dressed with the precision of a man who either had nowhere else to go or was meticulously planning his escape. His crisp, white-collared sports shirt and navy blue shorts looked fresh out of the package as if he had bought them specifically for this occasion, only to instantly regret his decision. The sandals on his feet were so spotless they might as well have come with a warning label: “For display purposes only.”

Maurice radiated the enthusiasm of someone attending a surprise tax audit. If this were a beach day, he’d be the guy hunched under a too-small umbrella, clutching a lukewarm beer like it was his only friend, and glaring daggers at the carefree seagulls circling above, as if they were personally responsible for all the miseries in his life. Every inch of him screamed that he’d rather be anywhere but here, and the irony was that he looked like he was dressed for a casual day out, just not one that involved other human beings.

To Maurice, this gathering was less of a spiritual intervention and more of a cruel and unusual punishment. His body language said, “I’m here under duress,” and his eyes, narrowed to slits, darted around the group as if calculating the quickest exit. It was clear that Maurice wasn’t here to bare his soul—he was here to endure the ordeal with as much stoic misery as possible. With a degree in computer science and the personality of a dial-up modem, Maurice was the poster child for disillusionment. Recently divorced and demoted from homeowner to condo dweller in Harbor City, he shared this nugget of personal failure with all the enthusiasm of someone recapping their latest colonoscopy. His intro was short, sour, and dripping with enough bitterness to make a lemon blush. You could tell Maurice wasn’t here to find inner peace—he was here because the thought of a one-on-one with the Abbot made him more uncomfortable than the idea of being stuck in a dentist’s chair.

Sitting next to Maurice was Jason, the group’s designated eye candy. With his languid gray eyes, full lips, and high cheekbones, Jason looked like he’d just stepped off the set of a Calvin Klein ad. But beneath the chiseled exterior was a life insurance salesman and mixed martial arts fighter who’d spent his formative years studying jiu-jitsu and muay thai to protect his siblings from their alcoholic father. His good looks and business success were a smokescreen for the social anxieties and commitment issues that plagued him. “I’m here to find answers,” he said, his voice dripping with the kind of melodrama usually reserved for soap operas.

Finally, there was Howard Burn, the Abbot’s right-hand man, who looked like he’d been assembled from spare parts left over from a mad scientist’s experiment. Tall and lanky with a head of perfectly coiffed black hair, Howard had the angular, contemplative face of someone who took himself way too seriously. He clutched a notebook in his lap, furiously scribbling notes like a star student at Cult Leader 101. When he introduced himself, it was with all the joy of a man who’d just been informed his house was on fire. “It has been my great pleasure to work for the Abbot for the last three years,” he said, his tone suggesting that “pleasure” was a foreign concept to him. Before joining the Abbot’s merry band of misfits, Howard’s life had been a blur, a meaningless existence spent wandering from one menial job to the next. But the Abbot had changed all that, and for the first time, Howard felt like he had purpose—presumably one that involved handing out a lot of cornbread cakes.

The Abbot beamed at Howard like a proud father, the kind who gives his kid a pat on the back for finally tying his own shoes. “Well said, my son,” his smile seemed to convey as if the entire room was one big happy family.

But then the interrogation began, and any illusion of a cozy kumbaya moment evaporated faster than a politician’s promise after election day.

The Abbot, who’d suddenly transformed from a benevolent guru into a reality TV judge on a power trip, fixed his steely gaze on Abigail. “We’ll start with you,” he declared, like a dentist about to extract a tooth without anesthesia. “Small-town girl, former fast-food overlord, now a landscaper, and you’re still spiraling from that breakup. Jennifer, wasn’t it? She moved in with someone else—someone you actually considered a friend—and now you’re wallowing in betrayal like a sad country song. All this wallowing has blinded you from your gifts.”

Abigail blinked, probably wishing she could shrink into her cargo shorts and disappear. “I don’t have any gifts that I know of,” she muttered, clearly hoping that modesty might serve as an escape hatch.

The Abbot’s smile was as sharp as a guillotine. “Oh, but there’s the matter of your left pinkie, now a charming little hook, thanks to your early attempts at butchering a pumpkin with a serrated knife. What were you, eight years old? Trying to carve a jack-o’-lantern or auditioning for a role in Sweeney Todd?”

Abigail nodded meekly.

“Show them,” the Abbot commanded as if this was the grand unveiling of some macabre art piece.

Obediently, Abigail held out her hand, and there it was: her pinkie, eternally frozen in a grotesque hook. The finger, sliced at the joint below the knuckle, was now more calcified appendage than human flesh—a monument to bad luck and worse kitchen skills.

“Yes, the hook,” the Abbot intoned, as if he were introducing the world’s eighth wonder. “A marvel, truly. It saved your life during that robbery in Barstow, blinded your would-be thief like a weaponized claw, and has been a godsend for lugging groceries into the house. You’ve even used it to hook tools while landscaping, but you’ve been missing out on its real potential.”

Abigail stared at the Abbot like he’d just told her she could time travel with her toenails.

“What you don’t realize,” he continued, his voice dripping with condescension, “is that your little pinkie isn’t just a handy-dandy grocery hook. It’s a supernatural antenna. Whenever you’re near something or someone steeped in dark secrets or supernatural energy, your pinkie will tingle, twitch, or maybe even do the macarena—whatever it does to warn you that you’re in the presence of danger. You’ve got a sixth sense attached to your hand, my dear.”

The Abbot then motioned for her to stand up. “Go on, stand next to Maurice and wave your pinkie in front of him like you’re dowsing for water. But don’t actually touch him; just let your psychic appendage do its thing.”

Abigail, clearly wondering what sort of circus act she’d signed up for, obliged. As she moved her pinkie around Maurice’s head, she wrinkled her nose. “There’s something off about his head,” she announced, as Maurice stared ahead with the same enthusiasm as a DMV clerk.

“Something wrong? With Maurice’s head?” the Abbot said, feigning shock like a bad soap opera actor. “You don’t say! But you’re right. His head is literally messed up.”

Maurice, looking like he’d just been told his dog died, barely reacted.

The Abbot turned to Maurice, his tone shifting to that of a doctor delivering a grim prognosis. “Maurice, my boy, you suffer from migraines, but not just any migraines. No, your headaches are like the universe’s cruel joke—they’re precursors to natural disasters, the kind of catastrophes people write disaster movies about. They’re called Black Swan Events. You’ve got the power to sense them before they happen, but until you harness this gift, you’re just a walking, talking barometer of doom. Learn to control it, and you might just be able to save us from the next apocalypse—or at least predict when we’ll need to evacuate.”

Maurice’s expression remained blank, perhaps pondering whether he’d wandered into a cult or just the world’s weirdest self-help group.

Abigail, meanwhile, looked at her pinkie like it was a divining rod, realizing that in this absurd reality, even her freakish hook might have its own twisted kind of magic.

The Abbot, with an air of condescending benevolence, motioned to Abigail to walk toward Stinky. She raised her pinkie—now more hook than finger—over the simian-faced warehouse worker, who stared at it like it was a deranged bumblebee.

“His nose,” she declared with the gravitas of someone revealing the cure for cancer. “He can smell things.”

“Very good,” the Abbot crooned as if speaking to a particularly dim-witted child.

“But not normal things,” she added, turning to the Abbot for reassurance. “He can smell evil!”

The Abbot nodded, his eyes twinkling with mock seriousness.

“He can smell it in people. He knows when they’re lying.”

“And what does it smell like, pray tell?” The Abbot asked, leaning in as if the answer might be the meaning of life.

“Ammonia,” she said, wrinkling her nose.

Stinky chimed in, “I smell ammonia all the time.”

“Of course, you do,” the Abbot said, as if this were the most natural thing in the world.

Stinky turned to his brother Larry with a smirk. “When you said you couldn’t loan me that money, I smelled ammonia. You were lying to me!”

The Abbot, now in full guru mode, said, “Your nose, Stinky, is a lie detector.”

Stinky’s face twisted into a look of bewildered relief. “All my life, I thought I had some kind of medical condition. When I was a kid, they ran all these tests because I kept saying everything smelled like cleaning supplies.”

“Of course they found nothing,” the Abbot said, taking a languid sip of cucumber water as if he were above such pedestrian concerns.

“But if the world is full of evil, why don’t I smell ammonia all the time?” Stinky asked, clearly not understanding the subtlety of his “gift.”

“Evil, my dear boy, comes in shades,” the Abbot said, like he was explaining quantum physics to a toddler. “You need to fine-tune your nose to detect varying levels of malevolence.”

He then turned his attention to Larry, who looked like he’d rather be anywhere but here. The Abbot motioned for Abigail to wave her pinkie hook over him, and she did so with all the enthusiasm of someone stirring a pot of gruel. She looked baffled. “I’m not getting anything… wait, there’s a pulse, like a two-four beat.”

Larry grinned, “That’s ‘Float On’ by The Floaters. I listen to it whenever I’m anxious. Helps me chill.”

The Abbot’s face soured at Larry as if his disciple’s slow thinking were testing his patience. “You don’t feel pain, do you?”

“Not really,” Larry said, shrugging. “Last year, I had a root canal. Brought my earbuds and played ‘Float On’ on repeat, and it was like I wasn’t even in the chair.”

The Abbot sighed, clearly disappointed. “You rely too much on your phone. You must learn to summon the song within your mind. Only then can you truly suppress pain.”

Larry’s face twisted in confusion. “But isn’t pain a good thing? Like, a warning system?”

The Abbot’s patience wore thin. “Most humans crumble at the slightest discomfort. Your power allows you to transcend pain, to unlock your full potential. Or would you rather remain a common oaf?”

Larry still didn’t look convinced, but the Abbot wasn’t one to be deterred by something as trivial as logic. His gaze slid over to Jason, a guy who looked vaguely familiar, like one of those retail cashiers you always see but never remember where. Jason was already fidgeting like a kid caught sneaking candy, his nerves practically screaming “Get me out of here.”

“Now, let’s see what our friend Abigail can sense about you,” the Abbot said, leaning in with the kind of enthusiasm usually reserved for people about to tell you you’re in for the deal of a lifetime—if you just hand over your credit card first.

Abigail, that beacon of confidence, hovered her pinkie in the air like she was trying to tune into Jason’s internal radio. Finally, her pinkie landed somewhere near his waist. “Your back… it’s messed up,” she declared, like she was diagnosing a flat tire.

Jason winced. “Chronic pain from a car accident two years ago. Acupuncture helps, but it’s still pretty bad.”

The Abbot sneered like Jason had just admitted to preferring instant coffee. “Acupuncture? Weakness incarnate. Your pain is a gift, Jason. Embrace it, and you’ll become five times stronger than the strongest man alive. Ignore it, and you’ll remain the pathetic creature you are.”

Jason blinked, trying to process the avalanche of nonsense the Abbot had just unloaded. “So, my back pain is… super strength?” He looked like he was about to ask if this whole thing was an elaborate prank.

“Precisely,” the Abbot said, with the smug satisfaction of a man who just solved the world’s energy crisis by suggesting we all power our homes with good intentions. “But only if you stop running from it.”

I realized, with a sudden jolt, that Jason wasn’t just vaguely familiar—I knew him. But from where? Fidgeting in my seat, I blurted out, “Jason, do we know each other?”

Before Jason could answer, the Abbot’s gaze swung toward me with all the subtlety of a wrecking ball. His nostrils flared like a bull about to charge, and I was suddenly sure he could smell my fear. “You’ll get your turn, but do not speak out of place,” he snapped, like a third-grade teacher reprimanding a kid for talking during recess.

He turned back to Abigail, clearly eager to get back to his performance of “Mystical Leader Extraordinaire.” “See what you can find out about Graham,” he instructed, as though I were next in line at a spiritual deli counter.

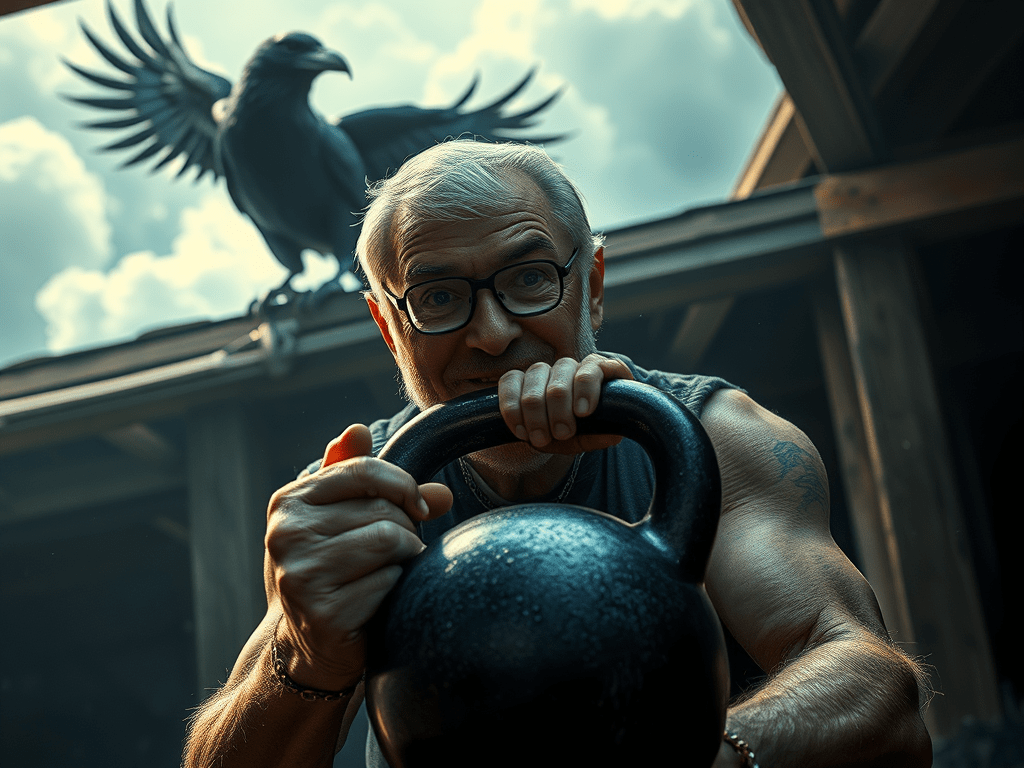

Abigail moved her magical pinkie over me, her face twisting in confusion like she was trying to figure out a Sudoku puzzle with half the numbers missing. “I’m getting… flapping. Like wings. Bats? No… crows! Huge crows!” She said this with the conviction of someone announcing the discovery of a new planet.

The Abbot’s eyes gleamed like a kid who just found the last Golden Ticket. “Yes, Graham has an affinity for crows—Gravefeathers, to be exact. They bring him messages from the other side, but he must learn to listen.”

I raised an eyebrow, now officially in *what the hell* territory. “Gravefeathers? Is this some kind of joke?”

“Far from it,” the Abbot said with a smile so condescending it could curdle milk. “The Gravefeathers have chosen you. Your task is to decode their messages, to fulfill our mission.”

“And what exactly is this mission?” I asked, now thoroughly regretting every life choice that had led me to this tent.

“All in good time,” the Abbot said, his tone so patronizing it was a wonder he didn’t pat me on the head. “For now, you must prepare.”

As if on cue, Howard Burn—looking like a villainous butler from a B-movie—emerged from the shadows carrying trays covered in tinfoil, like a waiter in some dystopian restaurant. “As a token of your commitment,” the Abbot intoned, “I offer you each a cornbread cake.”

My skepticism reached new heights. “What’s the catch?” I asked, eyeing the tray like it might contain some kind of mind-control device. “Is this cake magic?”

The Abbot’s face twisted into that all-too-familiar condescending smirk. “Magic? No. But consuming it is a test of trust, a way to align yourselves with the universe’s energies. And it tastes pretty damn good, too.”

Howard handed me a slice, and against my better judgment, I took a bite. To my horror, it was delicious. The cake was a golden, moist masterpiece, with a caramelized top that hinted at hidden sweetness. The flavors of honey and vanilla danced with almond and cornmeal, while a subtle cinnamon undertone lingered just long enough to make me question all my life choices up to this point.

I devoured the cake like a starving man, only to find myself choking on my own gluttony. The Abbot, ever the gracious host, handed me a glass of cucumber water, which I gulped down as if my life depended on it.

“I could eat this for breakfast, lunch, and dinner,” I mumbled, wiping crumbs from my face like the classy individual I am.

Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed a large black crow perched on the gate post, its fiery eyes boring into me with the unmistakable message: Enjoy your cake, you idiot. You’re in for one hell of a ride.