My journey with claustrophobia is not a quirk. It is a full-blown, sweat-drenched neurological prison riot. And nowhere does this disorder stage a more operatic coup than in two places: the dentist’s chair and the bowels of Universal Studios, Studio City.

Let’s start with the latter—a cautionary tale that should be printed on the back of every park map. I should never have stepped foot in that glorified mall of overpriced grease traps and postmodern carnival barkers wearing epaulets, who reeked of mothballs and dashed dreams. But I did it—for my twin daughters. For my wife. For the illusion that fatherhood sometimes requires nobility.

The fatal mistake? Boarding the Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey ride, a title that now feels like prophecy. After a Kafkaesque hour in line, I was shoehorned into a toddler-sized aircraft seat, and then came the final insult: a steel bar clamped down on my chest like it was sealing me into a medieval torture rack. My 52-inch ribcage was not consulted. My lungs issued an immediate protest.

As the ride lurched forward into a black tunnel engineered by Satan himself, I realized I was not going to survive. I began pleading, then shrieking for them to stop the ride—a desperate man reduced to primal terror. Mercifully, the passengers next to me joined in my hysteria, and their collective outcry finally penetrated the headset of some underpaid engineer who ground the machine to a halt. A stoic security guy with a Secret Service haircut approached as I peeled myself out of the deathtrap.

“You want to debrief me in the trauma tent?” I muttered, trying to laugh through the ash cloud of my dignity.

Fast-forward to a few weeks later: I’m back in another chamber of horrors—Dr. Howard Chen’s dental office. A kind, soft-spoken man, Dr. Chen has the patience of a monk and the eyes of someone who’s seen too much. During a routine procedure, he inserted a rubber bite block into my mouth—also known as the Mouth Prop from Hell. It jammed my jaw open, restricted my ability to swallow, and in seconds, transported me back to that Potter ride with its clamping harness and tunnel of doom.

I shot up from the chair, peeled off my flannel shirt like it was doused in napalm, and stood hyperventilating while sweat poured down my face like I’d just run the Boston Marathon with a fever.

Dr. Chen asked gently, “Are you going to be okay, Jeff?”

“I can’t have this rubber thing in my mouth,” I gasped, holding it like it was radioactive.

He removed it. Deep breaths. Back in the chair. We finished the procedure bite-block free, no further incidents—except for my lingering shame.

My visits to Dr. Chen are a multisensory assault. I am what polite society would call a “super smeller.” What that means in a dental context is that I’m stewing in a noxious stew of clove oil, latex gloves, glutaraldehyde, and ghostly wafts of tooth dust from patients past. Throw in the sound of Neil Diamond warbling over the speakers and it becomes less a cleaning and more a ritualistic descent into madness.

Every visit turns existential. I begin contemplating my soul, my legacy, and the probability that I’ll die while getting a fluoride rinse. It’s the only time I think about the afterlife more than I do during a colonoscopy—and that includes the part when they say, “You may feel a little pressure.”

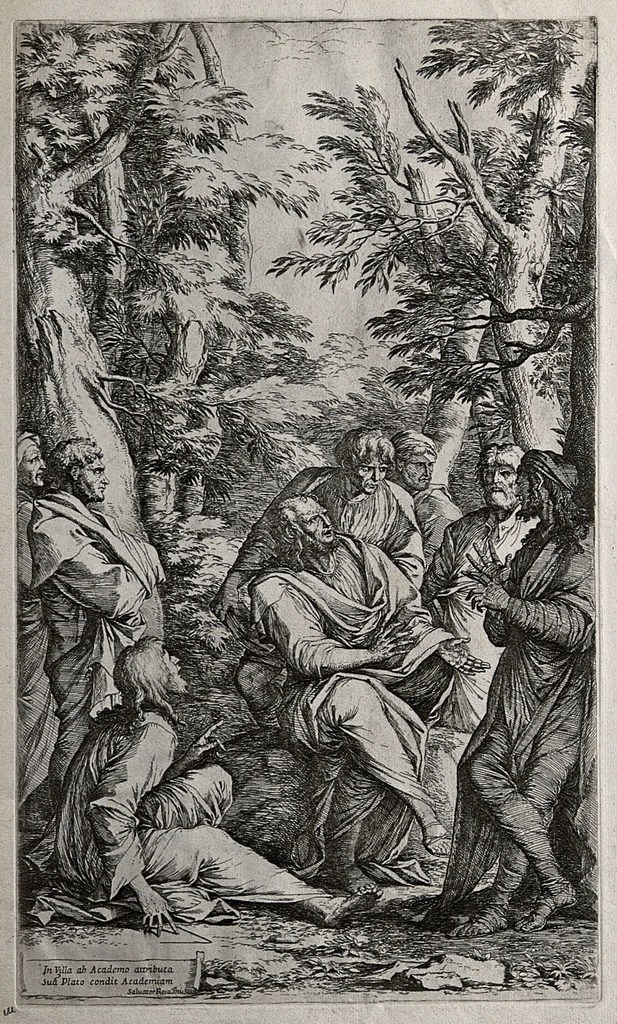

To his credit, Dr. Chen is a saint. He accommodates all my neuroses, never rushes me, and tries to soothe me with words that sound like Buddhist proverbs run through a dental insurance filter. “Let the Sonicare do the work,” he tells me. “But I don’t trust it,” I reply. “Then you must learn to trust.” “But I am a man of doubt.” “That, Jeff,” he says, “is obvious.”

At my most recent appointment, he warned me of potential decay under an old filling. “We may need to do a root canal.” I responded like a man learning he’d tested positive for eternal damnation.

“What can I do to stop this?”

“Cut the sugar. Don’t brush like you’re sanding drywall.”

“So what you’re saying is, I’m threading the needle here.”

“Basically, yes.”

“Doctor, I crave absolutes.”

“Join the club.”

Dr. Chen’s resignation to life’s uncertainty is what keeps me coming back. That, and the knowledge that no other dentist could possibly endure the psychological obstacle course that is my biannual cleaning.

After my last visit, dazed from polishing paste and light dental trauma, I left the office only to nearly reverse my car into a black SUV. The horn blast nearly cracked my molars. As I sat there recovering, I looked up and saw Dr. Chen watching me from behind the blinds—no longer smiling, but staring with the flat, weary eyes of a man who had just confirmed what he’d long suspected: his patient was, in fact, completely insane.

And he was right.