What if AI is just the most convenient scapegoat for America’s long-running crisis of stupidification? What if blaming chatbots is simply easier than admitting that we have been steadily accommodating our own intellectual decline? In “Stop Trying to Make the Humanities ‘Relevant,’” Thomas Chatterton Williams argues that weakness, cowardice, and a willing surrender to mediocrity—not technology alone—are the forces hollowing out higher education.

Williams opens with a bleak inventory of the damage. Humanities departments are in permanent crisis. Enrollment is collapsing. Political hostility is draining funding. Smartphones and social media are pulverizing attention spans, even at elite schools. Students and parents increasingly question the economic value of any four-year degree, especially one rooted in comparative literature or philosophy. Into this already dire landscape enters AI, a ready-made proxy for writing instructors, discussion leaders, and tutors. Faced with this pressure, colleges grow desperate to make the humanities “relevant.”

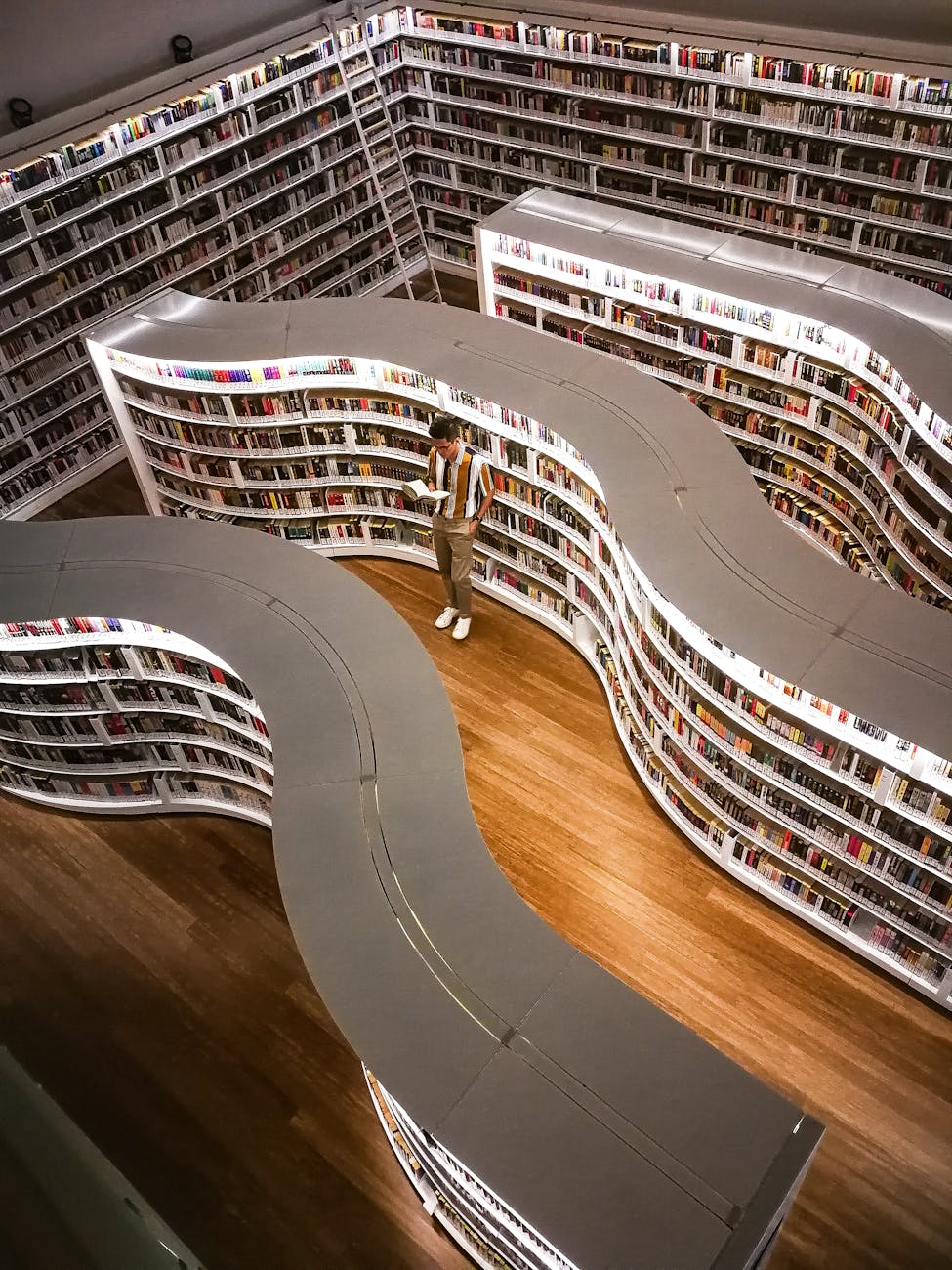

Desperation, however, produces bad decisions. Departments respond by accommodating shortened attention spans with excerpts instead of books, by renaming themselves with bloated, euphemistic titles like “The School of Human Expression” or “Human Narratives and Creative Expression,” as if Orwellian rebranding might conjure legitimacy out of thin air. These maneuvers are not innovations. They are cost-cutting measures in disguise. Writing, speech, film, philosophy, psychology, and communications are lumped together under a single bureaucratic umbrella—not because they belong together, but because consolidation is cheaper. It is the administrative equivalent of hospice care.

Williams, himself a humanities professor, argues that such compromises worsen what he sees as the most dangerous threat of all: the growing belief that knowledge should be cheap, easy, and frictionless. In this worldview, learning is a commodity, not a discipline. Difficulty is treated as a design flaw.

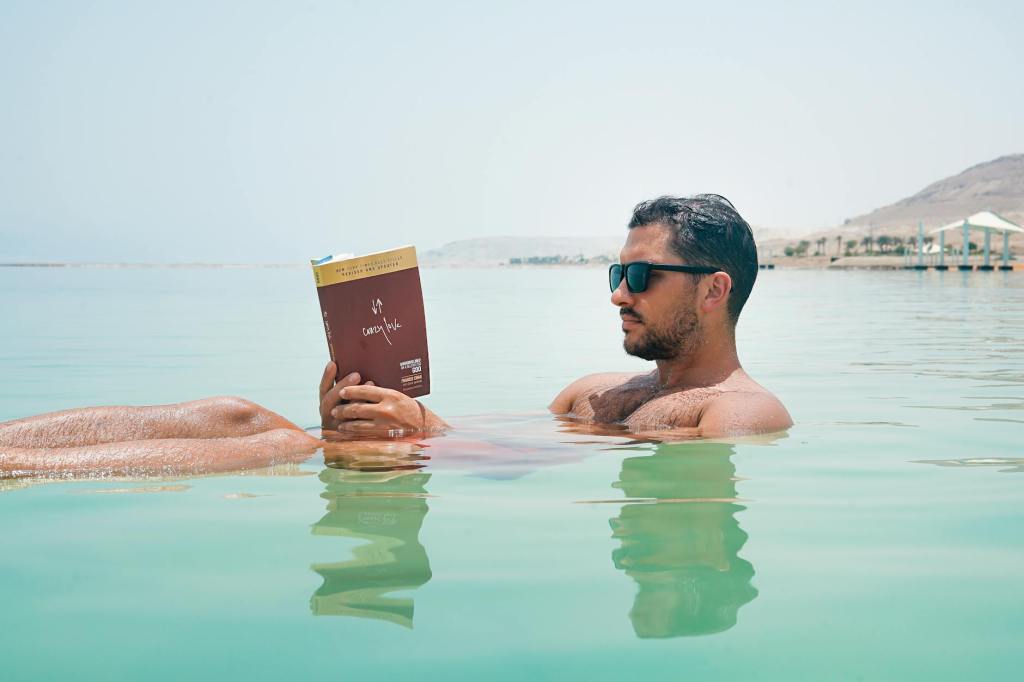

And of course this belief feels natural. We live in a world saturated with AI tutors, YouTube lectures, accelerated online courses, and productivity hacks promising optimization without pain. It is a brutal era—lonely, polarized, economically unforgiving—and frictionless education offers quick solace. We soothe ourselves with dashboards, streaks, shortcuts, and algorithmic reassurance. But this mindset is fundamentally at odds with the humanities, which demand slowness, struggle, and attention.

There exists a tiny minority of people who love this struggle. They read poetry, novels, plays, and polemics with the obsessive intensity of a scientist peering into a microscope. For them, the intellectual life supplies meaning, irony, moral vocabulary, civic orientation, and a deep sense of interiority. It defines who they are. These people often teach at colleges or work on novels while pulling espresso shots at Starbucks. They are misfits. They do not align with the 95 percent of the world running on what I call the Hamster Wheel of Optimization.

Most people are busy optimizing everything—work, school, relationships, nutrition, exercise, entertainment—because optimization feels like survival. So why wouldn’t education submit to the same logic? Why take a Shakespeare class that assigns ten plays in a language you barely understand when you can take one that assigns a single movie adaptation? One professor is labeled “out of touch,” the other “with the times.” The movie-based course leaves more time to work, to earn, to survive. The reading-heavy course feels indulgent, even irresponsible.

This is the terrain Williams refuses to romanticize. The humanities, he argues, will always clash with a culture devoted to speed, efficiency, and frictionless existence. The task of the humanities is not to accommodate this culture but to oppose it. Their most valuable lesson is profoundly countercultural: difficulty is not a bug; it is the point.

Interestingly, this message thrives elsewhere. Fitness and Stoic influencers preach discipline, austerity, and voluntary hardship to millions on YouTube. They have made difficulty aspirational. They sell suffering as meaning. Humanities instructors, despite possessing language and ideas, have largely failed at persuasion. Perhaps they need to sell the life of the mind with the same ferocity that fitness influencers sell cold plunges and deadlifts.

Williams, however, offers a sobering reality check. At the start of the semester, his students are electrified by the syllabus—exploring the American Dream through Frederick Douglass and James Baldwin. The idea thrills them. The practice does not. Close reading demands effort, patience, and discomfort. Within weeks, enthusiasm fades, and students quietly outsource the labor to AI. They want the identity of intellectual rigor without submitting to its discipline.

After forty years of teaching college writing, this pattern is painfully familiar to me. Students begin buoyant and curious. Then comes the reading. Then comes the checkout.

Early in my career, I sustained myself on the illusion that I could shape students in my own image—cultivated irony, wit, ruthless critical thinking. I wanted them to desire those qualities and mistake my charisma as proof of their power. That fantasy lasted about a decade. Eventually, realism took over. I stopped needing them to become like me. I just wanted them to pass, transfer, get a job, and survive.

Over time, I learned something paradoxical. Most of my students are as intelligent as I am in raw terms. They possess sharp BS detectors and despise being talked down to. They crave authenticity. And yet most of them submit to the Hamster Wheel of Optimization—not out of shallowness, but necessity. Limited time, money, and security force them onto the wheel. For me to demand a life of intellectual rigor from them often feels like Don Quixote charging a windmill: noble, theatrical, and disconnected from reality.

Writers like Thomas Chatterton Williams are right to insist that AI is not the root cause of stupidification. The wheel would exist with or without chatbots. AI merely makes it easier to climb aboard—and makes it spin faster than ever before.