Every morning during my teenage years, I’d stagger out of bed and make my daily plea to the heavens: “God, please grant me the confidence and self-assuredness to ask a woman on a date without suffering from a full-blown cerebral explosion.” And every morning, God’s response was as subtle as a sledgehammer to the forehead: “You’re essentially a walking emotional landfill, a neurotic mess doomed to wander the planet bereft of charm, romantic grace, and any semblance of healthy relationships. Get used to it, buddy.” And thus commenced my legendary odyssey in the land of perpetual non-dating.

This was not the grand design I had envisioned. No, the blueprint was to be a suave bachelor, just like my childhood idol, Uncle Norman from The Courtship of Eddie’s Father. At the ripe age of eight, I watched in awe as Uncle Norman demonstrated his revolutionary kitchen hack: why bother with dishes when you can devour an entire head of lettuce while standing over the sink? He proclaimed, “This way, you avoid cleanup, dishes, and the pesky inconvenience of sitting at a table.” In that glorious moment, I was struck with a revelation so profound it reshaped my entire existence. The Uncle Norman Method, as I would grandiosely dub it, became my life’s guiding principle, my personal beacon of satisfaction, and the defining factor of my existence for decades.

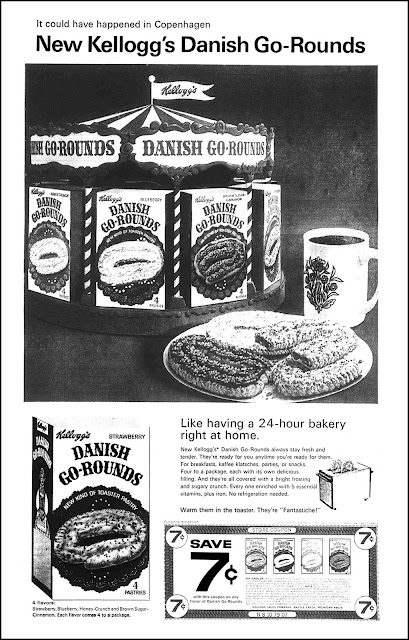

Channeling my inner Uncle Norman, I envisioned a life of unparalleled convenience. My bed would be perpetually unmade because who needs sheets when you have a trusty sleeping bag? I’d never waste time watering plants—plastic ones were far superior. Cooking? Please. Cereal, toast, bananas, and yogurt would sustain me in perpetuity. My job would be conveniently located within a five-mile radius of my house, and my romantic escapades would be strictly zip code-based. Laundry? My washing machine’s drum would double as my hamper, and I’d simply press Start when it reached capacity. Fashion coordination? Not a concern, as all my clothes would be in sleek, omnipresent black. My linen closet would be repurposed to stash protein bars, because who needs linens anyway?

I’d execute my grocery shopping like a stealthy ninja, hitting Trader Joe’s at the crack of dawn to dodge crowds, while avoiding those colossal supermarkets that felt like traversing a grid of football fields.

Embracing the Uncle Norman Way wasn’t just a new approach to dining; it was a radical overhaul of my entire lifestyle. The world would bow before the sheer efficiency and unadulterated convenience of my new existence, and I would remain eternally satisfied, basking in the glory of my splendidly uncomplicated life.

Of course, it didn’t take long for my delusion to expand into a literary empire—or at least, that was the plan. The world, I was convinced, desperately needed The Uncle Norman Way, my magnum opus on streamlining life’s most tedious inconveniences. It would be part manifesto, part self-help guide, and part fever dream of a man who had spent far too much time contemplating the finer points of lettuce consumption over a sink. Each chapter would tackle a crucial element of existence, from the philosophy of single-pot cooking (aka, eating directly from the saucepan) to the art of strategic sock re-wearing to extend laundry cycles. I even envisioned a deluxe edition featuring tear-out coupons for discounted plastic plants, a fold-out map of the most efficient grocery store layouts, and, for true devotees, a companion workbook to track their progress toward the ultimate goal: Maximum Laziness with Minimum Effort™.

Naturally, I imagined its meteoric rise to cultural dominance. Talk show hosts would marvel at my ingenuity, college professors would weave my wisdom into philosophy courses, and minimalists would declare me their messiah. Young bachelors, overwhelmed by the burden of societal expectations, would turn to my book in their darkest hour, finding solace in the knowledge that they, too, could abandon the tyranny of dishware and lean fully into sink-based eating. The revolution would be televised, one head of lettuce at a time.

Uncle Norman’s “system” introduced me to Chewtality–the ruthless prioritization of caloric input over culinary pleasure, a lifestyle doctrine where taste, ambiance, and social norms are discarded like expired salad dressing. It’s the stoic efficiency of consumption that transforms meals into mechanical refueling sessions, often while hunched over a sink, shirtless, chewing with the urgency of a man on parole from dignity.

Rooted in the gospel of Uncle Norman, Chewtality celebrates the unsentimental art of eating for sustenance and speed. Why savor when you can shovel? Why sit when you can hover? Why use plates when God invented hands and the stainless steel basin? This isn’t just a meal strategy—it’s a worldview: one where the blender pitcher is a chalice, the saucepan is a throne, and the lettuce head is both entree and ideology.

In its highest form, Chewtality produces a false sense of superiority—an unshakable belief that your Spartan choices signify enlightenment, when in reality, you’ve just spent dinner crouched over the sink eating raw spinach like a raccoon with a library card.