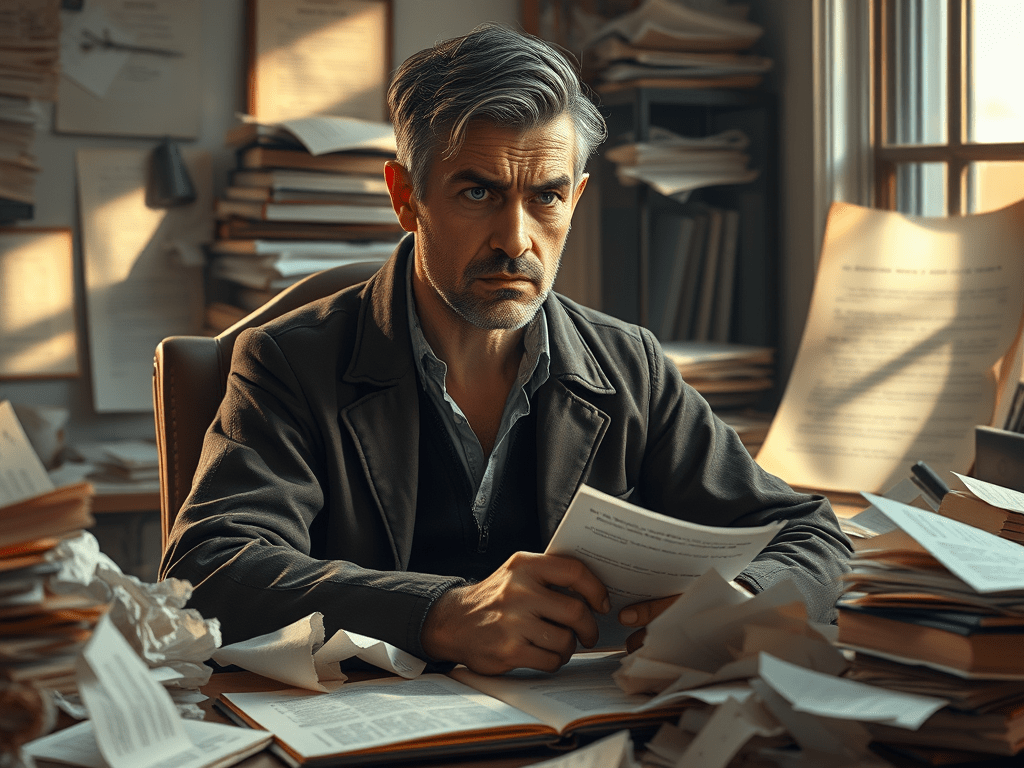

The aspiring writer, Manuscriptus Rex, writes not out of pure inspiration but from the unholy fusion of a chip on his shoulder and a raging inferiority complex. His desperation for a cure has somehow led him to the worst possible conclusion: that literary dominance is the only path to salvation. Anything short of conquering the literary world? Utter failure.

Why such extremes? Because Manuscriptus Rex is an eternal adolescent, emotionally stunted and incapable of nuance. Life is a brutal, binary equation—winners or losers, triumph or oblivion. There is no middle ground. And for those with just enough talent to know they’ll never be the best? The humiliation is unbearable. They sink into a spiral of self-loathing so profound, they start questioning why they were born in the first place.

This despair is captured well in the 1984 movie Amadeus, in which Salieri, the patron saint of mediocrity, spends his life gnashing his teeth over the fact that, for all his ambition, he’ll always be the guy in the cheap seats while Mozart, the true genius, takes center stage. Some might be tempted to draw the same parallel between Paul and Jesus, as if Paul were some whiny Salieri, shaking his fist at the heavens over his lack of messianic charisma. Dead wrong. Paul didn’t sulk in anyone’s shadow. He sharpened his writing tools, rearranged the spotlight, and made damn sure it was aimed squarely at himself.

How successful was Paul at making his writing stick? Let’s put it this way—his entire written output amounts to about eighty pages. Eighty pages. That’s not even the length of a middling beach read you’d abandon in an airport terminal. And yet, those pages have been scrutinized, weaponized, and dissected with more fervor than any artistic or literary masterpiece in human history.

I sit here, surveying the wreckage of five decades of my own writing, knowing full well that it will likely fade into the void, while Paul’s scant eighty pages have dictated the course of Western thought, politics, and religion for two thousand years. The word “influence” doesn’t even begin to cover it. This is literary world domination.

And was this tidal wave of influence accidental? Hardly. Paul wasn’t just writing to save souls—he was writing for his own immortality.

Pauline scholars love to point out that Paul wasn’t exactly thrilled with what the original apostles were peddling. Their Jesus still had training wheels—tied to Torah, saddled with Jewish law, bogged down by the pesky weight of tradition. Paul, on the other hand, had a better idea. His Jesus was purer, punchier, and more potent—a spiritual superfood untainted by Torah preservatives. And Paul wasn’t shy about it. He called it “my gospel”—not once, but over and over again, like a divine trademark. Forget the Jewish-flavored Jesus movement—Paul’s was gluten-free, carb-free, and straight to the Gentile bloodstream.

This wasn’t just a theological shift—it was a hostile takeover. Paul didn’t seem particularly interested in Jesus’ actual words. Sermons? Parables? “Love thy neighbor”? Small-time. Paul’s focus was on his own visions, his personal revelations, the ones that conveniently made himself the authority on Jesus. While Peter and James clung to their quaint Jewish traditions, Paul rebranded Christianity in his own image, rolling out a one-man revolution that sidelined the original apostles like outdated board members in a corporate coup.

And rabbi scholar Hyam Maccoby—never one to understate a theological conspiracy—takes it even further. According to The Mythmaker, Paul didn’t just step out from Jesus’ shadow—he steamrolled over it and rebranded Christianity as a Paul Production, with himself as lead architect of one of history’s largest religious empires. Salieri could only dream of that level of self-promotion.

But Paul didn’t just change the messaging—he altered the entire emotional foundation of Christianity. Maccoby doesn’t just accuse Paul of hijacking Christianity—he accuses him of rewriting the entire Old Testament like a hack screenwriter with a savior complex. The Jewish tradition of free will, strength, and human agency is replaced with Paul’s bleak vision of humanity—where people are helpless worms, groveling in the dirt, utterly incapable of doing anything good without divine intervention.

Fast-forward two millennia, and we’re still drowning in the wreckage of Paul’s inferiority complex—scrolling ourselves into oblivion, slaves to algorithms, locked in a spiritual malaise that might as well have been engineered by Paul himself. Maccoby paints Paul not as a mystical visionary, but as a man crippled by his own self-loathing, a former Pharisee who couldn’t hack it in Jewish law, so he torched the whole thing and built his own damn religion. And it worked.

Paul’s biggest marketing coup was turning Jesus into something unrecognizable. Gone was the Torah-loving Jewish teacher—in his place, a Hellenized God-man with cosmic grandeur. But Paul didn’t work alone. He had Luke, his personal spin doctor, crafting The Acts of the Apostles—a biblical infomercial designed to make Paul look like a tireless hero, smoothing out his awkward edges, burying any embarrassing missteps, and giving the real apostles about as much airtime as unpaid extras in Paul’s vanity project. The result? A Christianity that barely resembled anything Jesus actually taught, but one tailor-made for mass adoption.

It’s a corporate rebrand so slick that Paul might as well be the Steve Jobs of Western religion.

Paul didn’t just invent a religion—he invented religious dominance. His theology was designed for maximum influence, structured like a brilliantly engineered algorithm—one that self-replicates, adapts, and burrows into the psyche like a spiritual virus. You don’t just believe in Paul’s Christianity; you’re owned by it.

And this is where the connection to my own writing demon becomes uncomfortably clear.

Paul did what I’ve always wanted to do—he wrote something so potent, so inescapable, so monolithic, that it hijacked human consciousness for centuries. His letters didn’t just survive—they became the foundation for an entire civilization. And what is that if not the ultimate literary ambition?

The writing demon inside me has always whispered the same temptation—that if I just write the right book, if I craft my message well enough, if I design the perfect narrative, I can transcend obscurity, reshape reality, and carve my name into history.

Paul did it. He wrote himself into religious permanence, his eighty pages outlasting every empire, every cultural movement, every literary masterpiece.

And maybe that’s why I can’t stop thinking about him.

Because deep down, I know: Paul is the ghostwriter of my own ambition.