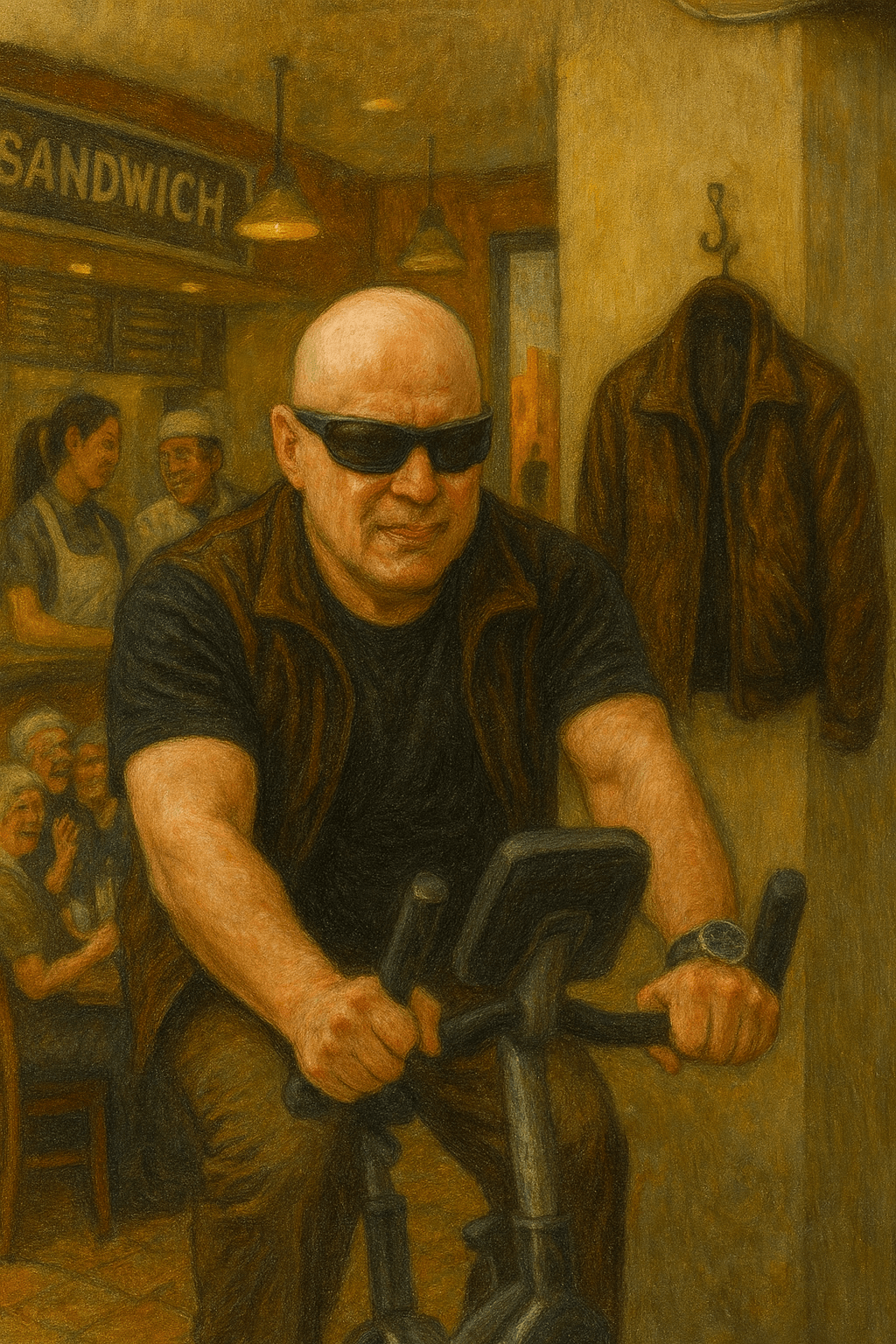

The irony gnaws at me: I’ve been a college writing instructor for forty years, yet thanks to what I’ll politely call “Internet poisoning,” I can barely read anymore. In the ’80s, I devoured Nabokov the way bodybuilders slam protein shakes—voraciously, obsessively, as if prose itself were anabolic fuel. Now? Most books I start end up abandoned halfway through, like gym memberships in February.

It’s not just the degraded Internet brain. There’s a physical component, too. Try cracking open a hard copy of Dostoevsky—his books are printed in fonts so microscopic they might as well be Morse code. But last night, I pulled a stunt: Crime and Punishment on my Kindle app, magnified in glorious large print across my 16-inch laptop. And I thought, “Hey, this isn’t half bad.” Almost breezy. Practically Dean Koontz with Russian orthodoxy.

Sure, it’s lugubrious. A brooding, handsome nihilist—today we’d label him an Incel—is plotting a crime that amounts to little more than a cry for a hug. Why did Dostoevsky obsess over this guy? What subterranean morbidity haunted the man?

So I play my mind a trick. I whisper: “This isn’t Russian gloom. This is metaphysical pop fiction. Dean Koontz with samovars.” That little spoonful of honey lets me swallow the medicine.

Maybe next I’ll tackle Demons. Then The Brothers Karamazov. Then The Idiot. And who knows? I may one day become a Dostoevsky scholar—simply by convincing myself I’m binging airport thrillers.