Spend a week with your family in Hawaii and you slip into a parallel time zone—one that ignores clocks altogether.

It starts the moment you survive five airborne hours in a 400-million-dollar jet. You land feeling like Superman, minus the cape and plus a mild dehydration headache. Within 24 hours, you’re barefoot, in swim trunks, marinating in mai tais, spooning loco moco into your face, and demolishing lilikoi pies. The weather is so perfect it feels like it was made to flatter you personally. Sunsets become private screenings. You have no deadlines, no alarms, no reason to measure the day except by the height of the tide or the level in your glass.

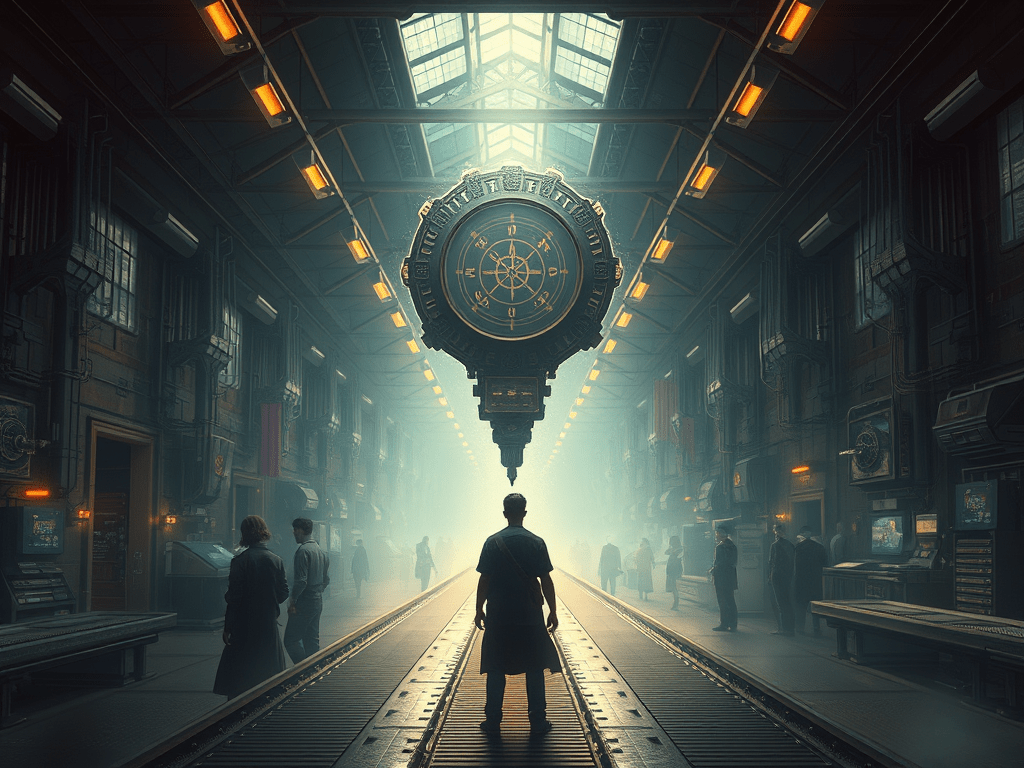

In this dimension, you’re not just on vacation—you’ve stepped outside of time. And outside of time means outside of death. Some corner of your brain starts whispering that you’re untouchable. Immortal.

That’s when the trouble starts.

The thought of getting back on a plane becomes revolting. It’s not just leaving Hawaii—it’s leaving Sacred Time and returning to Profane Time. Back to the grind where schedules nag and mortality hides in every bathroom mirror.

Even after you land at home, you’re not really home. You’re in a kind of sun-drunk denial, still hearing the ocean in your ears while the neighbor’s leaf blower whines outside. The older you get, the worse the hangover—because you know the clock is running, and the illusion of timelessness is an intoxicant more potent than any cocktail with a paper umbrella.

And then it’s over. You reenter the machine. Days are counted in emails, not waves. The tan fades, and with it the fantasy that you’ve cheated the countdown. That’s the real brutality of reentry—not the weather, but the eviction notice from the one place that convinced you, however briefly, that you could live forever.

So yes, I’m already searching for Big Island resorts. It’s not wanderlust—it’s a hunt for my next fix of immortality. And I know the danger. One day I might just stay.