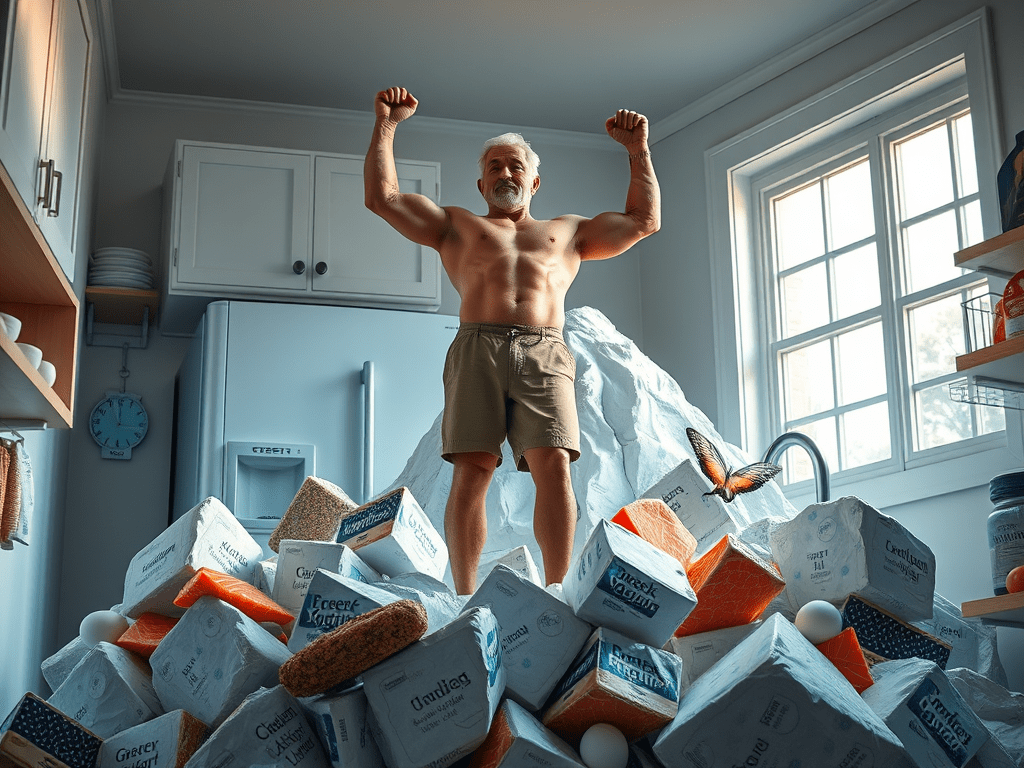

Each morning begins with a stare-down: me versus Proteinberg, the Everest of self-discipline, rising from my fridge like a smug Nordic god carved from blocks of Greek yogurt and slabs of salmon. It’s a cruel, relentless climb, strewn with the jagged boulders of eggs, tempeh, sardines, cottage cheese, soy milk, and the occasional whey protein landslide. Somewhere near the summit: a dollop of smug self-respect, earned only after choking down what tastes like Poseidon’s bait bucket mixed with barnyard runoff.

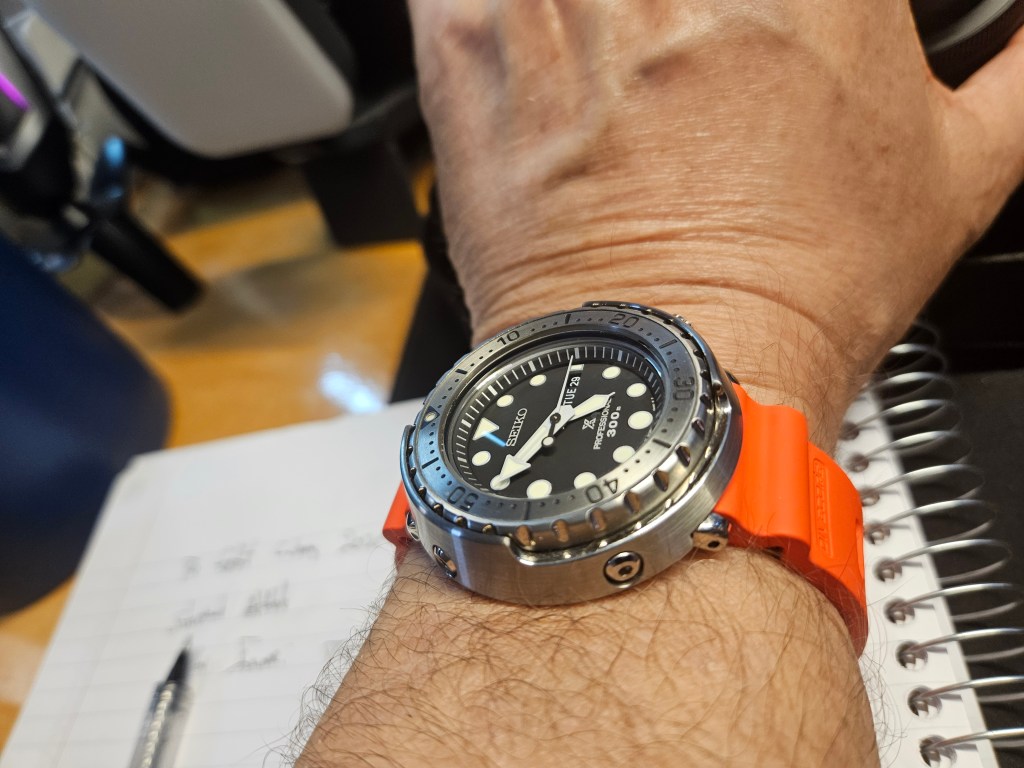

I’m 63, not that you’d guess it from the size of the kettlebells I swing five days a week like I’m auditioning for a reboot of 300: The 63-Year-Old Man Edition. My battle isn’t just with gravity—it’s with the creeping, gelatinous blob of abdominal fat that lurks like a metabolic Grim Reaper, threatening dementia, stroke, and the kind of death that begins with a raspy wheeze and ends in a hospital bed full of regret.

Climbing Proteinberg is my daily salvation. Miss a day, and the Carb Demons come knocking—those sugar-slick phantoms with snacky grins and buttery claws. They whisper of bagels and donuts, hijack my brain, and leave me sugar-drunk and shame-stained before lunch. But summit the Proteinberg? I walk tall. Satiated. Slightly disgusted, yes, but victorious.

It’s not just food. It’s ritual. It’s order in the chaos. A daily anchor in the storm of temptations that masquerade as comfort. As my wife brews her potent dark roast each dawn, the scent hits me like a monk’s bell calling me to vespers. I rise. I eat. I fight. I win. There is meaning in the climb, purpose in the discipline, and if not happiness, then at least its lean, unsalted cousin: peace.