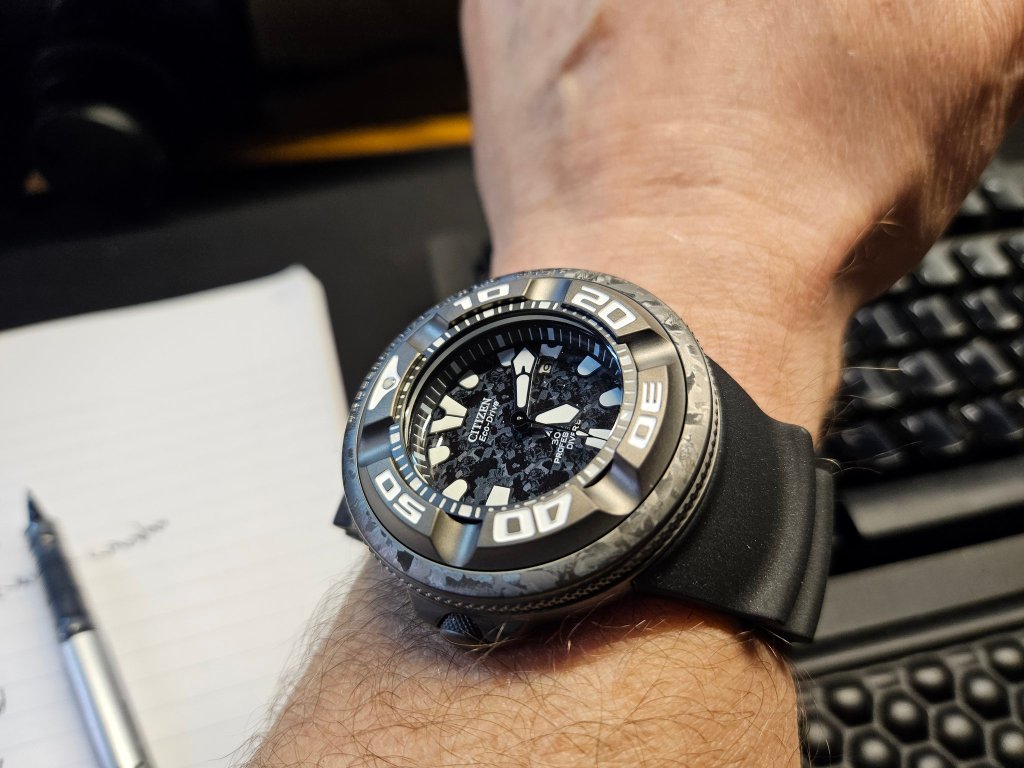

There is no sound more pathetic than the cry of the maudlin man—the self-appointed tragic hero of his own YouTube channel, sobbing between cuts of B-roll footage of his watch collection, mistaking emotional leakage for authenticity. He clutches his diver watches like talismans, convinced that the right lume or bezel action will finally make him whole. But his affliction is deeper than poor taste or consumer excess. He is in love with his own sorrow. And worse, he films it.

Cicero had a word for this spectacle: maudlin. It was not meant kindly. The maudlin man is drunk on his own emotional silliness, addicted to contrived drama, and tragically proud of his displays of overstated sorrow and giddy exuberance. In his pursuit of happiness, he has mistaken cheap feeling for moral virtue, dopamine for character, sentiment for wisdom. He is not mature. He is a teenager with a $5,000 Tudor.

The watch hobby, for all its mechanical beauty and aesthetic value, has become a theater of narcissistic self-performance. The YouTube wrist-roll has replaced the confessional. The thumbnail becomes the new sacred icon: face frozen mid-epiphany, a timepiece held up like a religious relic. Each upload, each gushing review, is a digital Rolex—plucked, examined, and consumed with trembling fingers and tears in the eyes. The tragedy is not that the watch community is ridiculous (though it often is), but that it has devolved into a factory of performative adolescence.

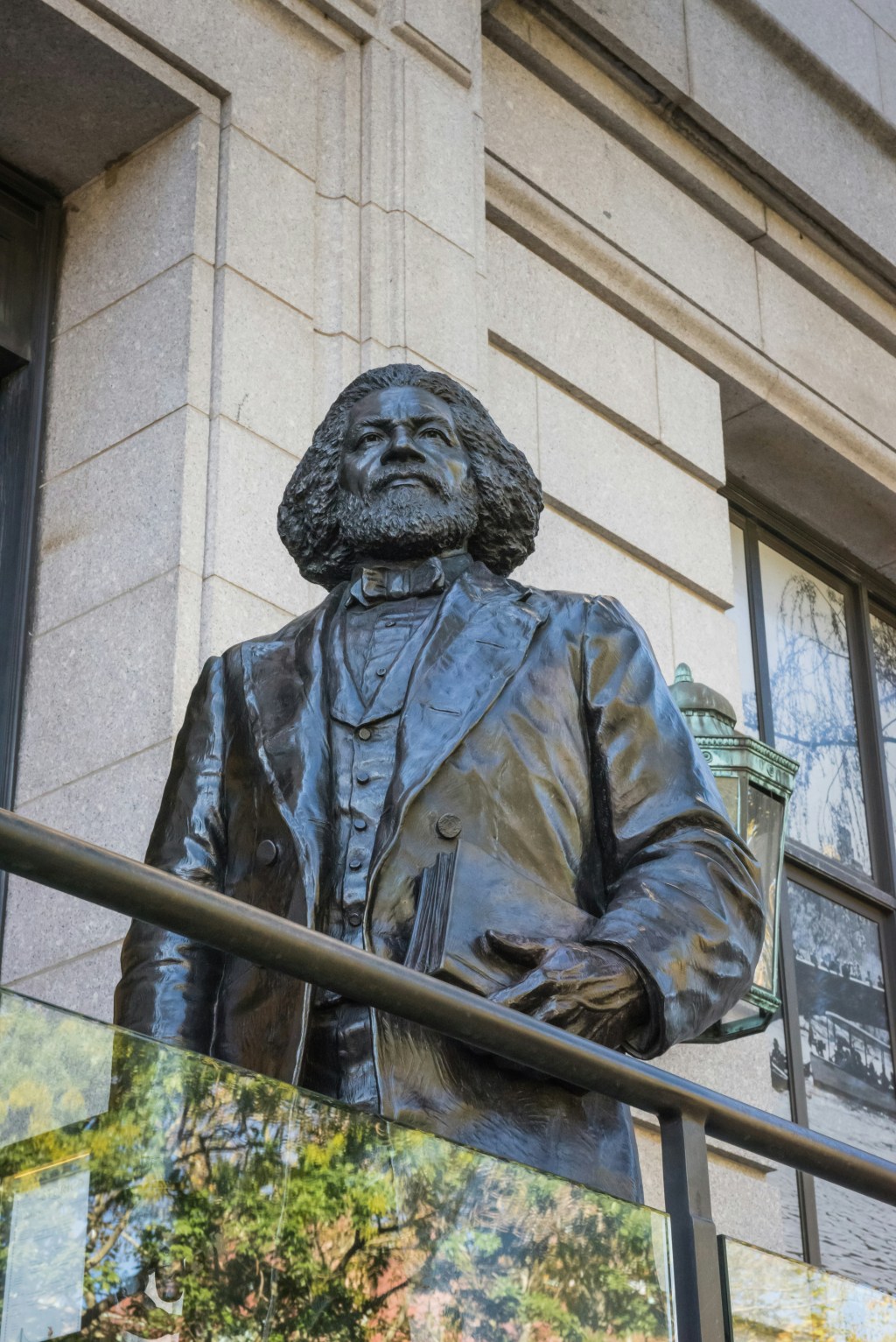

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time when the pursuit of happiness, as Jeffrey Rosen in The Pursuit of Happiness reminds us, meant the cultivation of moral character. Rosen draws from Franklin, Jefferson, and ultimately Cicero, who taught that happiness came not from pleasure but from the tranquil soul: one unbothered by fear, ambition, or maudlin eagerness. The watch obsessive is none of these things. His soul is rattled, consumed by longing, shaken by regret. He mistakes every new acquisition for a cure, every unboxing for a rebirth. But he is not reborn. He is merely re-dramatizing the same pathology.

Enter the maudlin man, the inner saboteur. He mocks, he sneers, and he tells the truth: that the maudlin man has no real restraint. That his self-recrimination is as performative as his self-praise. The maudlin man is cruel. He exaggerates the regret that comes from flipping watches like penny stocks; the hollow boast of self-control while our eBay watchlist grows longer by the hour; the dopamine crashes masked by overproduced videos and fake enthusiasm. We are not collectors. We are addicts with ring lights.

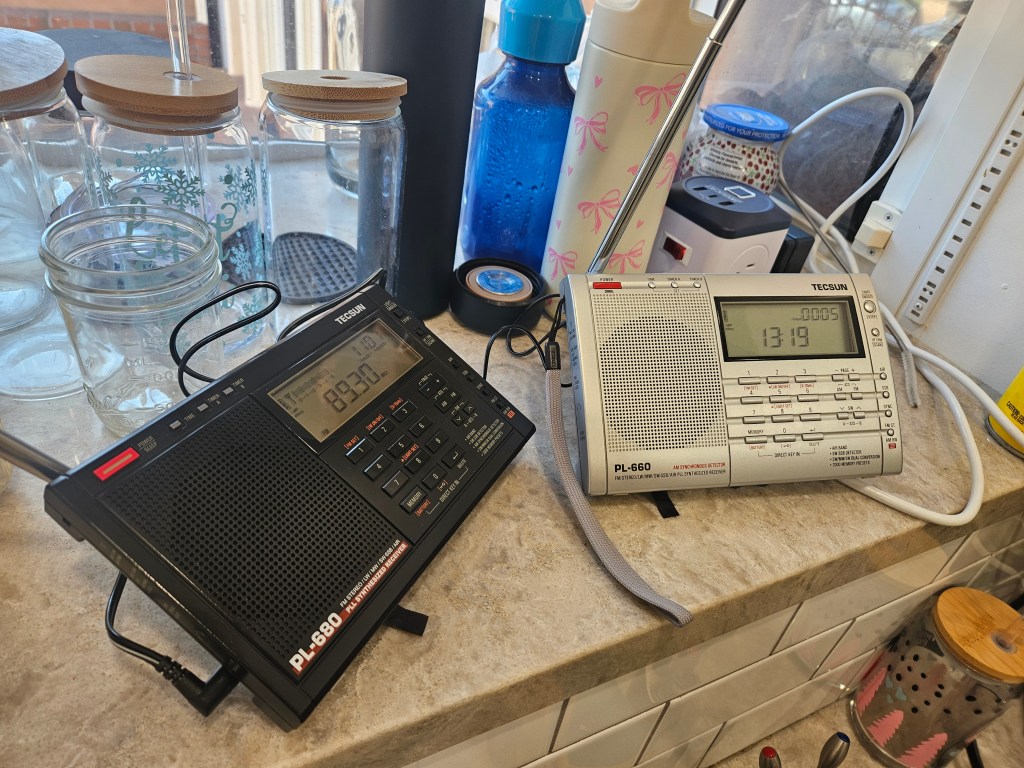

To be addicted to the watch hobby is to be afflicted with a thousand tiny regrets. We regret what we bought, what we sold, what we didn’t buy fast enough. We suffer from wrist rotation anxiety, Holy Grail delusions, false panic, and the creeping horror that we are just men who talk too much about case diameter. Our collections become mausoleums of past mistakes. We are haunted, not healed.

The only cure—if one exists—is a form of philosophical sobriety. Cicero called it temperance. Franklin called it moral perfection. Phil Stutz calls it staying out of the lower channel. It is the refusal to feed the drama. It is the decision not to narrate your regret as if it were wisdom. It is stepping back, stepping away, and recognizing that sometimes, the most radical act of self-possession is to stop filming.

This maudlin sickness isn’t limited to the horological hellscape. Social media itself is a dopamine machine engineered to keep us emotionally drunk. We live in a world of curated personas, algorithmic affirmation, and the self-cannibalizing loop of outrage and euphoria. As Kara Swisher notes in Burn Book, the tech elite have weaponized this environment for profit, fueling sociopathy with likes and retweets. They are not gods. They are billionaires who behave like wounded teenagers in private jets.

It is not a coincidence that the watch obsessive and the tech mogul share the same pathology: a hunger for affirmation masquerading as taste. They are the same creature, only one wears a G-Shock and the other a Richard Mille. Both are drunk on maudlin emotion. Both mistake attention for meaning.

What, then, is the alternative? It is to shut off the camera. To read. To walk. To live a life not curated but inhabited. To pursue virtue, not validation. To wear one watch and be content. To see, finally, that maudlin self-display is not depth, but decadence.

So here is the diagnosis, bitter but true: The maudlin man must die. Not literally, but spiritually. He must be silenced so the adult may speak. He must be buried so the man of character can rise. He must be mocked, dissected, exposed, and ultimately exorcised.

Only then, perhaps, will we stop crying over something as silly as the regret of sold watches we can never get back.

And maybe—just maybe—stop filming them.