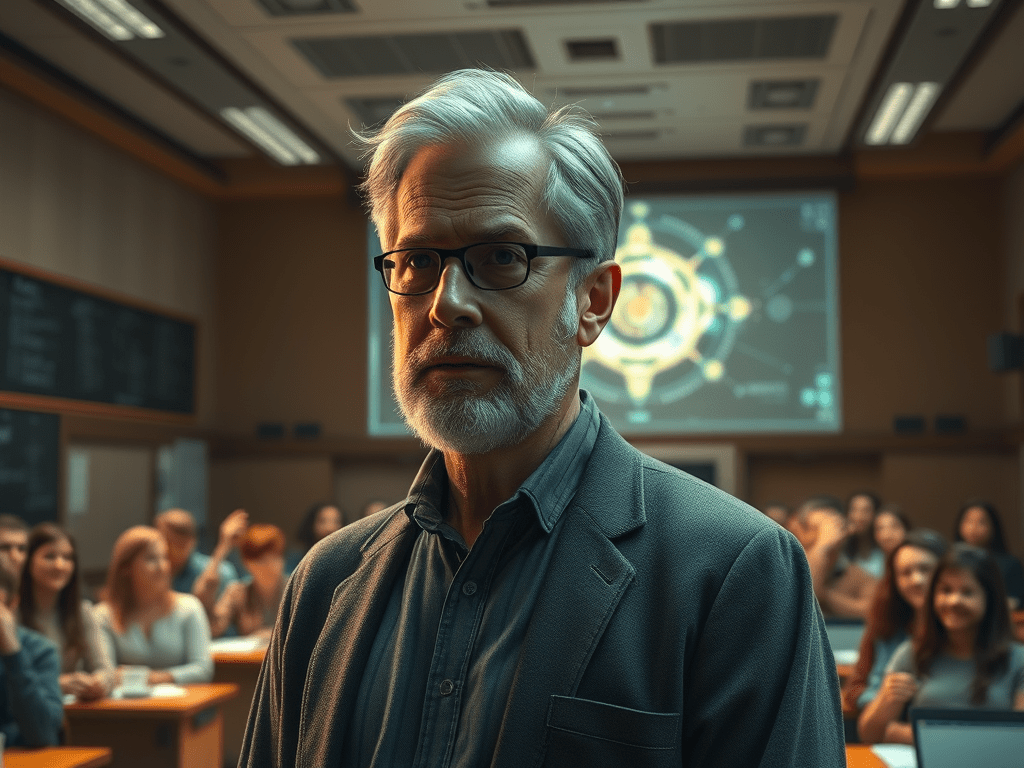

Yesterday, in the fluorescent glow of my classroom, I broke the fourth wall with my college students. We weren’t talking about comma splices or rhetorical appeals—we were talking about AI and cheating, which is to say, the slow erosion of trust in education, digitized and streamed in real time.

I told them, point blank: every time I design an assignment that I believe is AI-resistant, some clever student will run it through an AI backchannel and produce a counterfeit good polished enough to win a Pulitzer.

Take my latest noble attempt at authenticity: an interview-based paragraph. I assign them seven thoughtful questions. They’re supposed to talk to someone they know who struggles with weight management—an honest, human exchange that becomes the basis for their introduction. A few will do it properly, bless their analog souls. But others? They’ll summon a fictional character from the ChatGPT multiverse, conduct a fake interview, and then outsource the writing to the very bot that cooked up their imaginary source.

At this point, I could put on my authoritarian costume—Digital Police cap, badge, mirrored shades—and demand proof: “Upload an audio or video clip of your interview to Canvas.” I imagine myself pounding my chest like a TSA agent catching a contraband shampoo bottle. Academic integrity: enforced!

Wrong.

They’ll serve me a deepfake. A synthetic voice, a synthetic face, synthetic sincerity. I’ll counter with new tech armor, and they’ll leapfrog it with another trick, and on and on it goes—an infinite arms race in the valley of uncanny computation.

So I told them: “This isn’t why I became a teacher. I’m not here to play narc in a dystopian techno-thriller. I’ll make this class as compelling as I can. I’ll appeal to your intellect, your curiosity, your hunger to be more than a prompt-fed husk. But I’m not going to turn into a surveillance drone just to catch you cheating.”

They stared back at me—quiet, still, alert. Not scrolling. Not glazed over. I had them. Because when we talk about AI, the room gets cold. They sense it. That creeping thing, coming not just for grades but for jobs, relationships, dreams—for the very idea of effort. And in that moment, we were on the same sinking ship, looking out at the rising tide.