In “AI Has Broken High School and College,” Damon Beres stages a conversation between Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff that lands like a diagnosis no one wants but everyone recognizes. Beres opens with a blunt observation: today’s high school seniors are being told—implicitly and explicitly—that their future success rests on their fluency with chatbots. School is no longer primarily about learning. It has become a free-for-all, and teachers are watching from the sidelines with a whistle that no longer commands attention.

Bogost argues that educators have responded by sprinting toward one of two unhelpful extremes: panic or complacency. Neither posture grapples with reality. There is no universal AI policy, and students are not using ChatGPT only to finish essays. They are using it for everything. We have already entered a state of AI normalization, where reliance is no longer an exception but a default. To explain the danger, Bogost borrows a concept from software engineering: technical debt—the seductive habit of choosing short-term convenience while quietly accruing long-term catastrophe. You don’t fix the system; you keep postponing the reckoning. It’s like living on steak, martinis, and banana splits while assuring yourself you’ll start jogging next year.

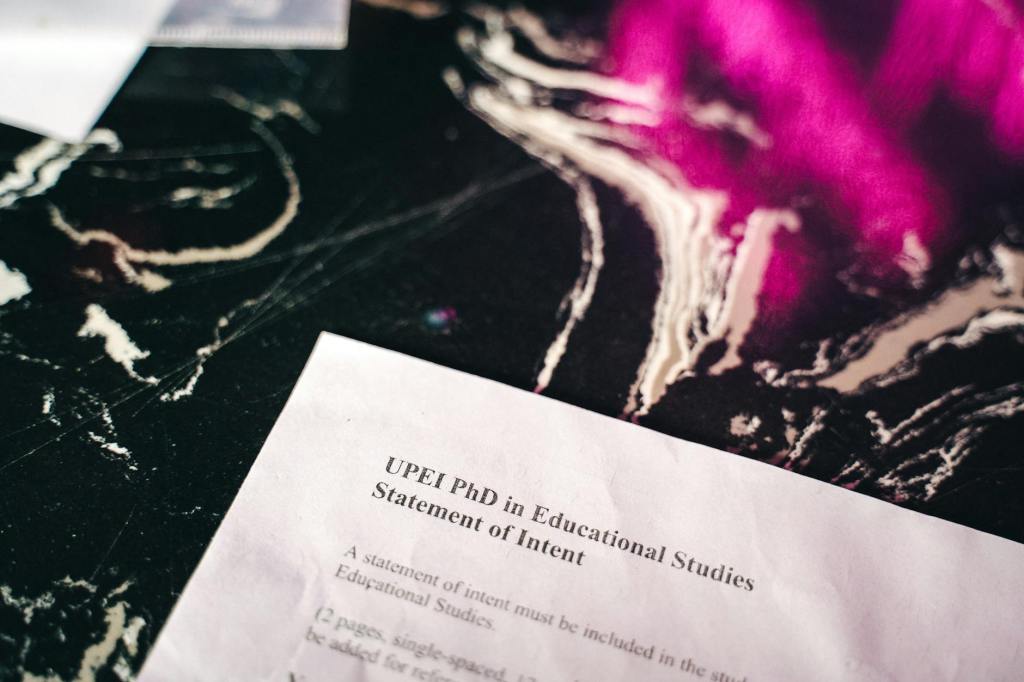

Higher education, Bogost suggests, has compounded the problem by accumulating what might be called pedagogical debt. Colleges never solved the hard problems: smaller class sizes, meaningful writing assignments, sustained feedback, practical skill-building, or genuine pipelines between students and employers. Instead, they slapped bandages over these failures and labeled them “innovation.” AI didn’t create these weaknesses; it simply makes it easier to ignore them. The debt keeps compounding, and the interest is brutal.

Bogost introduces a third and more existential liability: the erosion of sacred time. Some schools still teach this—places where students paint all day, rebuild neighborhoods, or rescue animals, learning that a meaningful life requires attention, patience, and presence. Sacred time resists the modern impulse to finish everything as fast as possible so you can move on to the next task. AI dependence belongs to a broader pathology: the hamster wheel of deadlines, productivity metrics, and permanent distraction. In that world, AI is not liberation. It is a turbocharger for a life without meaning.

AI also accelerates another corrosive force: cynicism. Students tell Bogost that in the real world, their bosses don’t care how work gets done—only that it gets done quickly and efficiently. Bogost admits they are not wrong. They are accurately describing a society that prizes output over meaning and speed over reflection. Sacred time loses every time it competes with the rat race.

The argument, then, is not a moral panic about whether to use AI. The real question is what kind of culture is doing the using. In a system already bloated with technical and pedagogical debt, AI does not correct course—it smooths the road toward a harder crash. Things may improve eventually, but only after we stop pretending that faster is the same as better, and convenience is the same as progress.