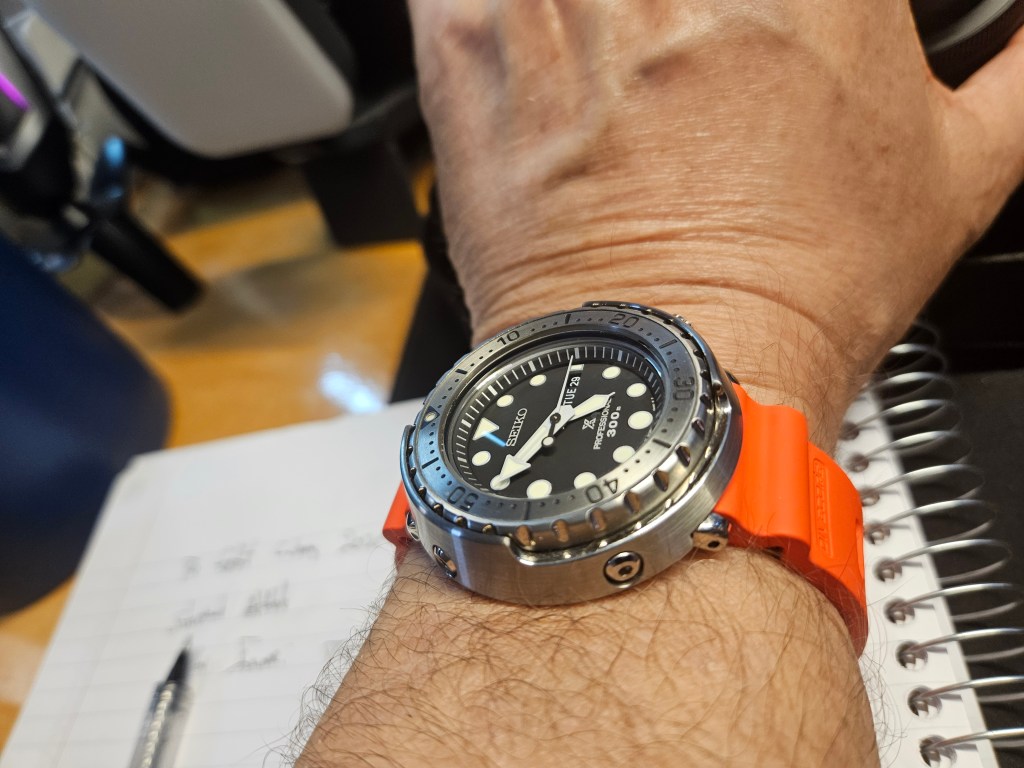

To understand the tortured psyche of the modern Timekeeper, you must first meet his most conniving organ: the Cavebrain. This primal relic, forged in an age of spear tips and saber-toothed tigers, was never designed for eBay, Instagram wrist shots, or limited-edition dive watches with meteorite dials. And yet, here he is in the 21st century, a man both blessed and cursed with opposable thumbs, a PayPal account, and a psychological need for existential renovation every time he clicks Buy It Now.

A high-ticket watch purchase for the Timekeeper is not a simple act of consumer indulgence—it is a rite of passage, a narrative arc, a full-blown identity reboot. He isn’t just buying a watch; he’s staging a personal renaissance, performing emotional alchemy with brushed titanium and spring-drive movements. He craves the sensation of getting something done—and if he can’t change his life, he’ll change his wrist.

But a new acquisition can’t simply squeeze into the old watch box like another hot dog in an overstuffed cooler. No, it demands sacrifice. One or more watches must be winnowed down, exiled like loyal but unremarkable lovers who just didn’t “spark joy.” There is drama here—drama more potent than remodeling a kitchen or repainting the bedroom a daring eggshell white. This is a domestic upheaval that matters. The arrival of a new timepiece—let’s call it “the new kid in town”—requires a realignment of the soul.

Now, for those poor souls unacquainted with Timekeeper theology, let me explain: He cannot simply collect indiscriminately. He is bound by the Watch Potency Principle, a dogma revered by enthusiasts. This principle states that the more watches a man owns, the less any of them mean. Like watering down bourbon, or stretching a heartfelt apology into a TED Talk, the essence gets lost. The once-sacred grails—the unicorns he hunted with obsessive glee—go sour in the dilution of excess. Only by restricting the herd to five to eight carefully curated specimens can he maintain potency and fend off emotional ruin.

Of course, there’s a devil in the details. The Timekeeper suffers from a chronic affliction known as Watch Curiosity. He’s always sniffing around the next shiny object, eyes darting at macro shots on forums, lurking on Reddit, and falling prey to influencers wearing NATO straps and faux humility. Inevitably, he pulls the trigger on yet another must-have diver, thus initiating the ritual purge. A watch he once swore eternal fidelity to must now be cast out—not because it’s inadequate, but because he has convinced himself that it is. This self-gaslighting feeds a demonic loop known as Watch Flipping Syndrome, wherein watches are bought, sold, and rebought with the desperation of a man trying to time-travel through retail therapy.

If the Timekeeper is lucky, if he can wrestle his impulses into a coherent, lean collection, he may briefly find peace. But peace is not his natural state. Beneath his curated restraint lies a restlessness, a gnawing sense that time—his most feared adversary—is standing still. His desire for a new watch is not about telling time; it’s about rewriting it. When he buys a new watch, he isn’t updating his collection—he’s updating himself. He wants change, achievement, rebirth.

Enter the Honeymoon Period—a temporary euphoria where the new watch becomes a talisman of transformation. He floats, rhapsodizes, posts gushing tributes on enthusiast forums. He becomes a preacher in the Church of the Chronograph, recruiting others to experience this miracle. The watch didn’t just change his wardrobe—it changed his life.

But, as all honeymoons do, the enchantment fades. The novelty rusts. What was once a grail becomes just another object—another timestamp on the long and winding road of emotional substitution. He finds himself, once again, alone with his Cavebrain, who, ever the unreliable life coach, whispers, “Maybe there’s something better out there.”

Thus, the cycle repeats—endless, compulsive, costly. The Timekeeper is not a collector. He is an evolutionary casualty. A caveman in a smartwatch world, still looking for meaning in a bezel.