In my quest to diagnose the writing demon that refuses to release me from its grip, I turned to Why We Write: 20 Acclaimed Authors on How and Why They Do What They Do, edited by Meredith Maran. In her introduction, Maran paints a bleak portrait of the literary life: writers waking before dawn, shackling themselves to their craft with grim determination, all while the odds of success hover somewhere between laughable and nonexistent.

She lays out the statistics like a funeral director preparing the bereaved: out of a million manuscripts, only 1% will find a home. And if that doesn’t crush your soul, she follows up with another gut punch: only 30% of published books turn a profit. Clearly, materialism isn’t the primary motivator here. Perhaps masochism plays a role—some deep-seated desire for rejection that outstrips the mere thrill of self-rejection. Or maybe it’s just pathology, an exorcism waiting to happen.

For those unwilling to embrace despair, Maran brings in George Orwell’s “four great motives for writing”: egotism, the pleasures of good prose, the need for historical clarity, and the urge to make a political argument. Sensible enough. No surprises.

Where things get interesting is Joan Didion’s take. Didion, never one for sentimentality, strips the writer’s motives bare: “In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even hostile act.”

Reading that, my eyes lit up with recognition. Didion had just sketched Manuscriptus Rex in perfect detail—the secret bully, the compulsive brain-hijacker who isn’t content to write in solitude but needs to occupy the minds of others, to install his worldview in their most private spaces.

Terry Tempest Williams, on the other hand, writes to confront her ghosts, a sentiment that deeply appeals to me. The idea of the writer as a haunted creature, forever pursued by stories that demand exorcism, feels not only true but inescapable.

But here’s the kicker—Maran makes it clear that the twenty writers in her book aren’t failures like me. They’re not Manuscriptus Rexes, howling into the void. No, they are the anointed ones, welcomed by publishers with open arms, bathed in the golden light of editorial gratitude.

And yet, they didn’t land on Mount Olympus by accident. They fought. They clawed their way up, word by painful word, which means they have something to teach—not just to their fans but to me, a self-aware Manuscriptus Rex still trying to understand what, exactly, makes him tick.

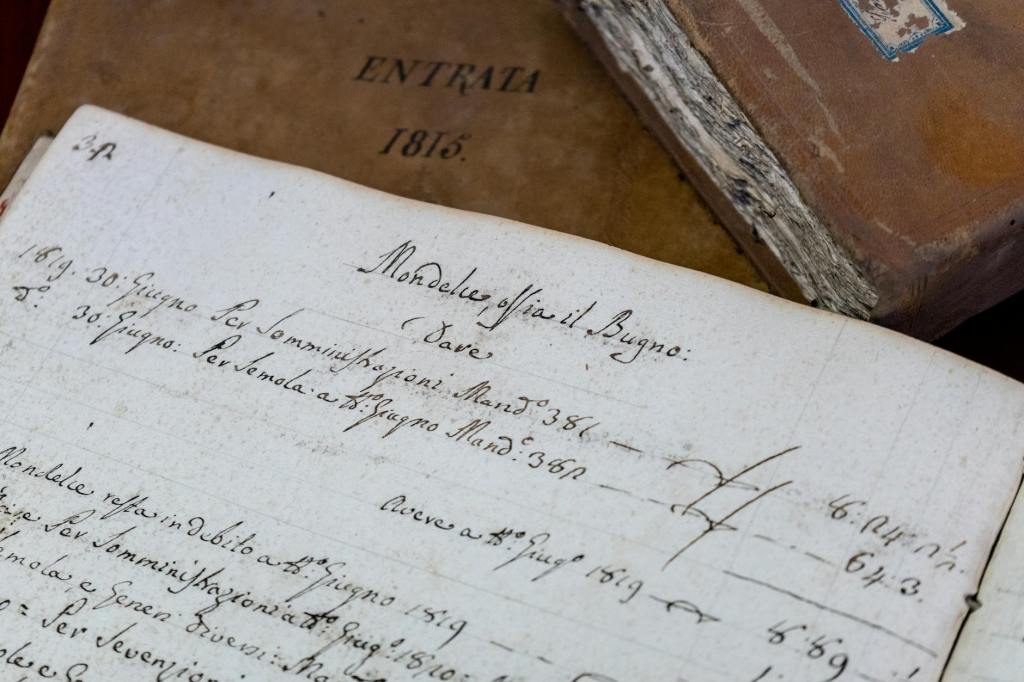

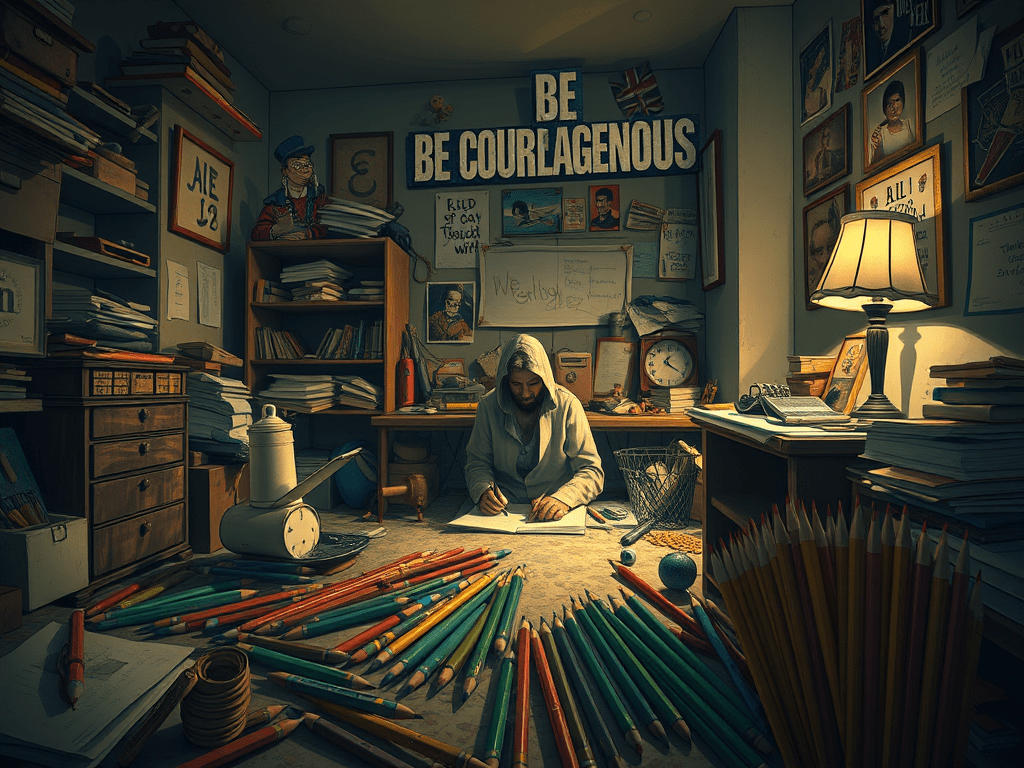

There is no shortage of delicious tidbits in Why We Write. Isabel Allende talks about the necessity of writing like a growing tumor that has to be dealt with or will simply grow out of control. She adds that even if she begins with a germ of an idea, the book has a life of its own. It grows from her unconscious obsessions and preoccupations, so that in the beginning she has not yet discovered what story she is going to tell. Also, she is a writer of ritual and routine. Every January seventh is the day before she starts writing a new book. She gathers all her materials in her “little pool house,” which she uses as her office. It is her sacred space to work, just “seventeen steps” from her home.

The idea of having two separate spaces—one for writing, one for everything else—fascinates me. It reminds me of something Martin Amis once told Charlie Rose: he needed to be a writer because toggling between the world of the novel and the earthly world created a kind of necessary duality, a parallel existence where imagination could thrive. For someone wired for storytelling, living between those two realities wasn’t just a luxury—it was a survival mechanism.

At home, Isabel Allende straddles two universes, one sacred, the other profane. And it calls to mind the lesson my college fiction professor, N.V.M. Gonzalez, drilled into us: a fiction writer must know the difference between sacred and profane time.

A great writer conducts these two temporal forces like an orchestra. Sacred time—mythic, timeless, symbolic—stretches beyond the clock, charging pivotal moments with fate, destiny, and the weight of history. It’s the crossroads where a single decision echoes through eternity. Profane time, by contrast, is the ticking metronome of daily existence—the coffee that goes cold, the unpaid bills, the search for a parking spot.

A great novel moves between the two—one moment steeped in cosmic significance, the next trapped in the drudgery of real life. A character might wrestle with divine purpose—but that won’t stop their Wi-Fi from cutting out mid-revelation.

Allende enters her writing enclave in a state of terror and exhilaration, grappling with ideas—some brilliant, some best left in the trash bin—while navigating stress, disappointment, and suspense. Her process feels high-stakes, and really, what is life without high stakes? A slow, numbing descent into low expectations, inertia, and existential boredom—a fate worse than failure.

Maybe writing addiction is just the relentless drive to keep the stakes high. Without it, life shrinks into a provisional existence, where survival boils down to the next meal, the next fleeting pleasure, the next song that momentarily sends a tingle up your spine—a desperate Morse code from the universe to confirm you’re still alive.

The writers in this book all share the same unshakable compulsion to write. For them, writing isn’t just a craft; it’s therapy, oxygen, a way to make sense of chaos. They write because they can’t not write—because failure to do so would send them spiraling into an existential crisis too dark to contemplate. Writing gives them self-worth, wards off insanity, and serves as the only acceptable coping mechanism for their undying curiosities. It isn’t a choice—it’s a chronic condition.

These successful authors write relentlessly, enduring the agony of writer’s block, self-loathing, and the horror of their own bad prose, all while clawing their way toward something better. And while I share their compulsions, I lack their stamina and focus. Reading about Isabel Allende’s fourteen-hour writing binges was my moment of clarity: I am not a literary gladiator. These novelists can paint vast landscapes of story without crapping out halfway. I, on the other hand, am a wind-sprinter—a lunatic exploding off the starting block, only to collapse in a gasping heap a hundred yards later, curl into the fetal position, and slip into a creative coma.

And this, I suspect, is the great torment of Manuscriptus Rex—an insatiable hunger to write the big book, clashing violently with a temperament built for sprints, not marathons. This misalignment fuels much of my artistic misery, my chronic dissatisfaction, and my ever-expanding graveyard of unfinished masterpieces.

Still, whatever envy and despair I felt reading about these elite warriors of the written word, this book offered a cure—I will never again attempt a novel unless divine intervention forces my hand. I’ve seen too many of my failed attempts, the work of a man pretending to be a novelist rather than one willing to endure the necessary rigor. But I do have another calling: identifying unhinged, demonic states in others.

Like a literary taxidermist, I want to capture these wild, self-destructive compulsions, mount them for display, and present them with maximum drama—not for amusement, but as cautionary tales. This is my work, my rehabilitation, the writing I was meant to do. And unlike novel-writing, it actually feels like a necessity, not a delusion.