The breeding ground for writing my many unreadable novels was the California desert, where my catastrophic literary judgment was rivaled only by my crimes against fashion. Allow me to paint you a picture of excess so garish that even Liberace would have staged an intervention.

There I was—a freshly minted full-time professor in a sun-scorched town, drunk on a heady cocktail of naïveté, unresolved teenage angst, and the disastrous influence of International Male and Urban Gear catalogs. To my 27-year-old mind, these catalogs weren’t mere collections of overpriced polyester; they were sacred texts, blueprints for the modern alpha male—or at least a man who looked like he managed a European nightclub and occasionally fled the country under mysterious circumstances.

But even my delusions had their breaking point. The pinnacle of my sartorial madness arrived in one final, glorious misstep—an outfit so egregious that it shattered the patience of my English Department Chair, a man whose tolerance, until that moment, had been almost biblical.

At first, my colleagues generously excused my increasingly bizarre wardrobe as “youthful exuberance” from a Bay Area transplant trying to assert some “big city” flair in a desert outpost where fashion trends arrive three decades late. But one fateful day, I pushed the boundaries beyond reason. I strutted into the campus like a peacock ready for a ballroom dance-off, dressed in tight Girbaud slacks that practically screamed, “I’m here to give a lecture, but I might also break into interpretive dance.” My feet were clad in Italian loafers, complete with tassels and tiny bells—yes, bells. Who needs socks when you’ve got bells?

But the crown jewel of this sartorial disaster—was the sage-whisper green pirate shirt. And when I say “pirate shirt,” I’m not talking about a whimsical Halloween costume. I’m talking about a translucent, billowing monstrosity that looked like it was plucked from the wardrobe of Captain Jack Sparrow after a particularly wild night of plundering. My bulging pecs were practically hosting their own TED Talk through the sheer fabric, and the effect was more Moulin Rouge than Macbeth.

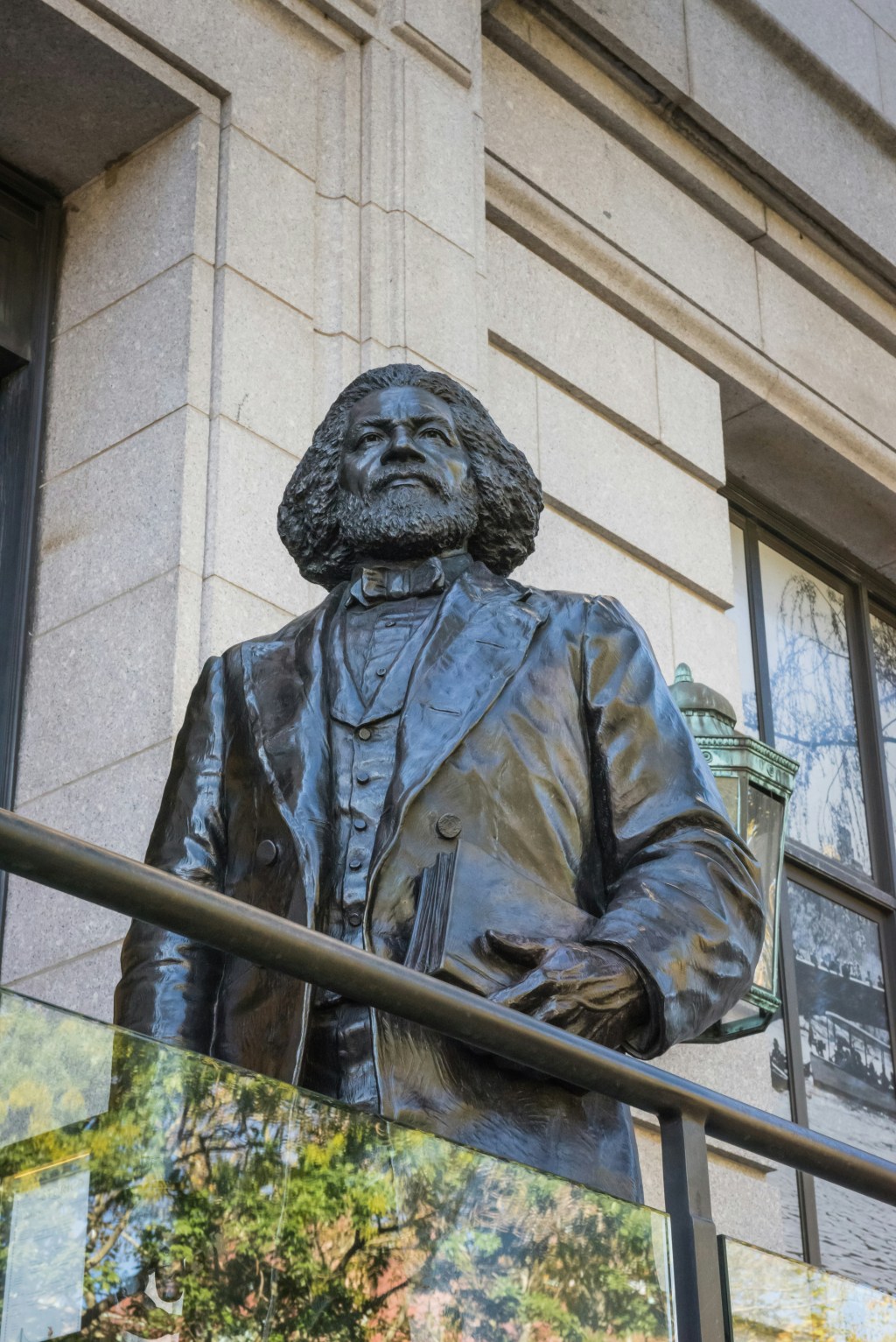

Word of my fashion blunder made it to Moses Okoro, our distinguished Chair, a no-nonsense scholar in his fifties who had traded the vibrant streets of Lagos for the dull sands of this backwater town. Moses prided himself on being a man of deep thought, the kind who savored life’s complexities and relished philosophical debates like a connoisseur of fine wine. In the rarefied circles he once frequented, he had been celebrated for his intellectual rigor, a reputation largely sustained by an essay he penned two decades earlier on a celebrated Nigerian novelist. The essay, which dissected themes of post-colonial identity with surgical precision, had been lauded as groundbreaking in its time, securing Moses’s place as a respected voice in academic and literary discussions. But the years had passed, and that once-prominent essay had become a relic—he still leaned on it like a crutch, bringing it up whenever the opportunity presented itself, hoping to rekindle the admiration it had once inspired.

By the time I got the midday summons to his office, I knew I was about to get the fashion red card. I walked in, and there was Moses—feet ensconced in some sort of luxurious foot-warmer device, a necessary accessory for his gout. He flashed me a grin that was half-amused, half-pitying like a man witnessing someone try to cook a steak with a hairdryer.

“Jeff,” he began, in a tone that suggested he was both fond of me and horrified by me. “You’re a striking figure, I’ll give you that. But this—” he gestured vaguely at the shimmering monstrosity draped over my torso—“is taking things too far. I can see more than I care to.”

I glanced down at my exposed chest and, for the first time, realized that my pecs were starring in their own soap opera under that filmy fabric. Moses continued, “I get it—a man with your bodybuilding prowess wants to flaunt it. But, Jeff, this is an academic setting, not Studio Fifty-Four. Be more of a professor and less of a Desert Peacock.”

He then instructed me to march straight home, ditch the pirate couture, and return dressed in something befitting a person who isn’t auditioning for a Vegas show. Before I could slink away in shame, Moses added with a smile, “Jeff, I like you. You’ve got potential. But let me remind you, this town is a fishbowl. Whatever you do in the morning, the whole town knows by lunchtime.”

That was the small-town way—a place where the smallest fashion faux pas became a full-blown scandal before the sun hit noon. As I left his office, I knew that my pirate shirt days were over, along with my delusions of dressing like the love child of Captain Morgan and Don Juan.

With a sigh, I trudged home to swap my dreams of high fashion for something a bit more… professorial.

***

I had no clue back then, but my tragic fashion choices as a young professor in the desert in the early ‘90s were the desperate impulses of a kid who’d missed his shot at feeling special and was clawing to reclaim a glory he’d fumbled away when he was a teenage bodybuilder.

As a recovering writing addict, I feel duty-bound to interrogate the roots of my affliction. I suspect my obsession with literary fame was a desperate attempt to fill the void left by a glory that always felt just out of reach. Surely, if I could be famous, I’d finally be whole. The restless gnawing inside me would stop.

This fantasy—this belief that success would grant me some grand, existential healing—must be the defining delusion of Manuscriptus Rex, the pitiful beast I have become. Like Linus in the pumpkin patch, I waited, not for the Great Pumpkin, but for the Great American Novel to descend and bless me with meaning.

I convinced myself that basking in literary fame would erase the sting of a squandered youth, a time when I was too clueless, too underdeveloped, too timid to seize life with the lust and gusto it demanded. That lost youth left a wound, and Manuscriptus Rex clung to the belief that writing—great writing—would be the magic salve. If I couldn’t reclaim my past, I could at least immortalize myself on the page.

It was a beautiful, seductive lie.

Flashback to 1981: I was working a job loading parcels at UPS in Oakland, on a low-carb diet that shredded me down to the bone. I was this close to contending for the Mr. Teenage San Francisco title. With a perfectly bronzed 180-pound frame, my clothes started hanging off me like a bad costume. That meant one thing: new wardrobe. Enter a fitting room at a Pleasanton mall, where I was trying on pants behind gauzy curtains when I overheard two attractive young women debating who should ask me out. Their voices escalated, full of hunger and competition, as if I was the last slice of pizza at a frat party. I pictured them throwing down on the store carpet, pulling hair and clawing at each other’s throats, all for the privilege of walking out with the human trophy that was me.

It was the golden moment I’d always dreamed of, my chance to bask in the attention and seize my shot at feeling like a demigod. So, what did I do? I froze like a deer in headlights, slapping on a look of such exaggerated indifference it was like laying out a welcome mat that said “Stay Away.” They took one look at my aloof facade and staggered off, probably mumbling about how stuck-up I seemed. But here’s the truth: I wasn’t a man full of myself—I was a coward hiding behind muscle armor.

For a short, fleeting period—from my mid-teens to early twenties—I was the kind of guy who could’ve sent Cosmopolitan’s “Bachelor of the Month” candidates sobbing into their pillows. But my personality was still crawling in the shallow end of the pool while my body was busy competing for gold medals. I had sculpted a physique that would make Greek gods nod in approval, but socially? I was like a houseplant that wilts if you talk too loudly. Gorgeous women practically threw themselves at me, and I responded with the warmth and enthusiasm of a mannequin. Behind all that bronzed, chiseled muscle was a scared little boy trapped in a fortress of self-doubt.

The frustration that consumed me as I stood there, watching those two retail employees squabble over me, was the same frustration that hit me like a truck a week later at the contest. I entered Mr. Teenage San Francisco as a “natural”—which is just a polite way of saying I didn’t juice and therefore shrank down to a point where I looked more like a wiry special-ops recruit than a bodybuilder. At six feet and 180 pounds, I had the lean, aesthetic “Frank Zane Look” just well enough to snag runner-up. But the guy who beat me was a golden-haired meathead pumped full of steroids and Medjool dates, which gave him muscles that looked inflated by a bike pump and a gut that seemed ready to explode from cramping.

The day after the contest, I was laid out at home, basking in the almost-victory and recovering from the Herculean effort of flexing through a nightmare lineup. Then the calls started pouring in. Strangers who’d gotten my number from the contest registry wanted me to model for their sketchy fitness magazines. Some sounded more like basement-dwelling creeps than actual photographers. I turned them down with all the enthusiasm of a nightclub bouncer dealing with fake IDs. But then one call stood out—a woman claiming to be an art student from UCSF, asking me to pose for her portfolio. Tempting, sure, but I politely declined.

Why? The reasons were as predictable as they were pathetic. First, I was drained from cutting down to 180 pounds and just wanted to curl up in a hole. Second, I was lazy. The thought of expending energy to meet a stranger sounded about as fun as a root canal. But the main reason? I was a professional neurotic, a certified worrywart who avoided human interaction like it was an airborne disease. The idea of meeting this mysterious woman in a San Francisco coffee shop filled me with a dread so profound that I felt like a cat eyeing a room full of rocking chairs.

By turning down those offers, I was throwing away the golden advice handed down in Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Arnold: The Education of a Bodybuilder. According to the Gospel of Arnold, I should’ve been leveraging my physique into acting gigs, business ventures, and political fame. But here’s the thing—I didn’t have Arnold’s larger-than-life charisma, his zest for adventure, or his overpowering drive to turn everything into a money-making opportunity. While Arnold was out charming Hollywood and turning flexing into fortune, I was content to crawl under a rock and avoid all forms of adventure and new connections. If there had been a way to market my body without ever leaving my room, I would’ve been the undisputed king of the fitness world.

Instead, I took a different path—one paved with introversion and leading straight to a career as a college writing instructor in a backwater desert town. By the time I hit twenty-seven, I was finally catching up socially—just in time to fantasize about all the chances I’d blown. Strutting around the desert in flamboyant outfits like a peacock trying to reclaim lost glory, I was determined to make up for all the opportunities I’d wasted, finally embracing the ridiculousness of who I’d become.