In I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional: The Recovery Movement and Other Self-Help Fashions, Wendy Kaminer lays waste to the therapeutic fads of the 1990s, particularly the trend of “reclaiming the inner child”—a ritual that took infantilization to near-religious extremes.

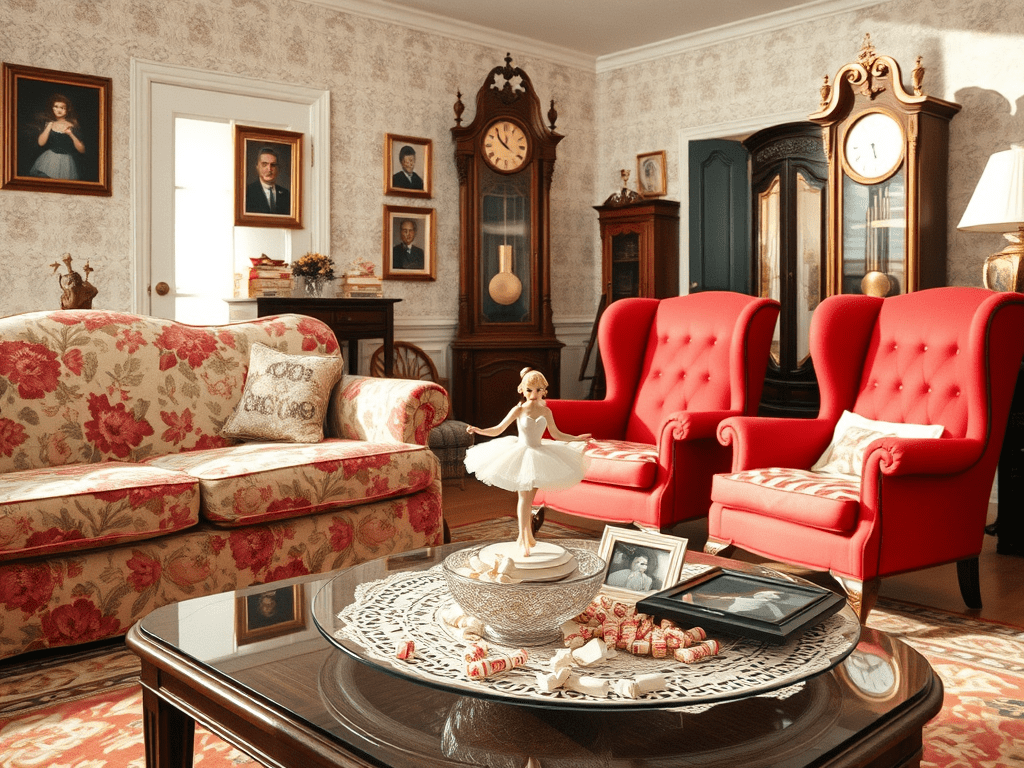

She describes John Bradshaw’s workshops, where grown adults with respectable careers arrived clutching teddy bears like traumatized toddlers, preparing to embark on a guided journey into the mansion of their past. There, as Bradshaw whispered encouragements, lower lips trembled, tears streamed, and a congregation of emotionally overqualified professionals sobbed into the polyester fur of their stuffed animals.

What floored Kaminer wasn’t the unhinged emotionalism—it was the sheer, shameless conviction. These people weren’t just indulging in a saccharine, self-indulgent spectacle—they were true believers, convinced that squeezing a doll and reliving some long-buried playground trauma was nothing short of a spiritual awakening.

Kaminer was not impressed. What others saw as self-reflection and healing, she saw as an infantilizing orgy of narcissism, a self-help séance in which grown-ups tried to resurrect their inner kindergartener, only to be possessed by a ghost that refused to leave.

Now, I’d like to say that my bullshit detector is too finely tuned for me to cradle a stuffed animal and regress into baby talk. But the bitter irony is that writing this memoir has forced me into my own brand of infantilization—just without the teddy bear and group cry session.

Nothing made this clearer than the pathetic spectacle of my post-Thanksgiving downfall, which started with a game of Russian roulette—except instead of a revolver, I played with rotting cabbage.

It all began when I decided to make chicken tacos—a wholesome, adult dinner choice. Unfortunately, the bag of shredded cabbage I retrieved from the fridge had been marinating in its own decay for two weeks, slowly transforming into hell’s compost pile.

The moment I tore open the bag, my wife recoiled with the dramatic flair of a crime scene detective stumbling upon a long-decomposed body. She clutched her nose, waved her hands like an exorcist warding off a demon, and issued a forensic report:

“That smells like a mix of a latrine and a horse’s taint.”

A normal person would have taken this as a warning. But, fueled by misplaced confidence and the hubris of someone who had survived worse, I dumped the cabbage on my tacos and dug in.

Hours later, my immune system, weakened by the Thanksgiving marathon of forced hospitality, collapsed like a debt-ridden empire. The virus that had been lurking in the shadows seized its moment, and by the next morning, I was a feverish, shivering wreck, contemplating my life choices between bouts of violent gastrointestinal reckoning.

It seems that you don’t need a stuffed animal and a therapy circle to regress into infancy. Sometimes, all it takes is spoiled cabbage and a ruinous lack of self-preservation.

Naturally, instead of exercising common sense, I channeled my inner cheapskate prophet. “Cabbage by its very nature has a funky scent,” I proclaimed with the confidence of a man who regularly courts disaster. “A little fermentation won’t hurt anyone.” My wife frowned and said, “It’s smelling up the entire kitchen.”

“We’ll be fine,” I insisted, scooping copious amounts of fetid-smelling cabbage onto my tacos like I was auditioning for a daredevil cooking show.

At dinner, I was the only one brave—or foolish—enough to eat it. Within an hour, my body issued a resounding, “You absolute moron.” No GI issues, but I felt like I’d been hit by a truck, reversed over, and then hit again. My head throbbed, my eyes were so sensitive to light I had to drape a T-shirt over my face just to listen to a Netflix show, and my energy flatlined by eight p.m. I crawled into bed, feeling like a half-baked zombie.

The next morning was worse. Still no GI problems, but the 101 fever and crushing fatigue made me question my will to live. I tried to eat some oatmeal and grapefruit, the culinary equivalent of punishment food, but even that felt like too much effort.

By day three, no improvement. I’d become a cautionary tale, researching induced vomiting and discovering it was far too late. Apparently, if you don’t purge immediately, the toxins settle in like an unwanted houseguest who insists on staying for five to seven days.

Being sick in my family makes everyone else suffer. Our teenage twins require constant care, frequent snacks that generate endless dirty dishes, and someone breathing down their necks to ensure homework gets done. My wife had to shoulder it all while I languished in my misery. I apologized profusely for my reckless hubris and promised, at the age of sixty-three, to turn over a new leaf—or at least stop eating ones that reek like death.

For decades, I’d treated eating old, moldy food like a badge of honor, quoting my dad’s immortal wisdom: “Pilgrims who ate blue cheese on the Mayflower survived disease while the mold-avoiders died.” It was as if I’d been brainwashed into believing spoiled food was a superfood. But this cabbage debacle—this hellish, cabbage-induced reckoning—put the fear of God in me. Never again would I be the fool who eats something that smells like a medieval torture chamber. This time, I mean it. The next funky bag of cabbage? Straight to the trash. May it ferment in peace.

As the alleged food-borne illness dragged on and my fever turned my brain into a swamp, I found myself pondering a morbid yet painfully stupid thought: What if I died because I was too cheap to toss a two-dollar bag of cabbage? Imagine the headline: “Man Perishes Over Discount Vegetables.” How could I ever forgive myself for such world-class idiocy? Worse, how could my wife ever forget that I lectured her with the smug confidence of a food-safety guru right before scarfing down a fatal dose of rotting produce? I’d be immortalized as the kind of hapless buffoon who wouldn’t even get a name in a Chekhov short story—just “The Idiot Who Ate the Cabbage.”

Then, because fever dreams and existential crises go hand in hand, another absurd thought hit me: How would my YouTube subscribers and Instagram followers know what happened to me? I’d be gone, but my accounts would still sit there, ghostlike, leaving them to wonder why the witty guy with the diver watches and snack obsession suddenly went dark. What a tragedy—I wouldn’t even get the chance to create a final piece of content documenting my own demise in comedic glory. A video titled, “How Cabbage Killed Me (And Why You Should Toss Yours)” would surely have gone viral.

This realization struck me as profoundly twisted: content creators care more about producing “engaging material” than their own mortality. Forget self-preservation—I was more upset that my audience might miss out on the hilarity of my self-inflicted cabbage-related downfall. The pathology runs deep: we’re so hooked on being performative, we’d probably narrate our own deaths if we could. Imagine me, breathless and feverish, croaking out, “Don’t forget to like, comment, and subscribe—assuming I make it to tomorrow.” The absurdity of it all made me laugh, which hurt, because even my ribs were exhausted from this cabbage-induced purgatory.

It was apparent I was so desperate to be relevant on social media that I had become a Gravefluencer–an influencer who extends his reach six feet under, ensuring even death is on-brand.

After five days of relentless illness, I had a phone consultation with my doctor about what I was sure was self-inflicted food poisoning. I laid out the symptoms with the kind of detail you’d expect from someone auditioning for a medical drama. My doctor listened patiently, then unceremoniously popped my bubble of absurdity. “This isn’t food poisoning,” she said. “You’ve got the flu. It’s going around.”

Just like that, my grand narrative of culinary hubris—the man who dared to defy rancid cabbage and paid the ultimate price—was dead. Instead, I was left with something far less glamorous: virulent flu. Part of me was relieved that I wasn’t poisoning myself with poisoned produce, but another part of me felt cheated. I’d lost the absurd, darkly comedic morality tale about a man so cheap he nearly killed himself over a two-dollar bag of cabbage. What a waste.

The doctor wasn’t exactly brimming with solutions, either. “Rest and stay hydrated,” she advised, the way you might tell a child to eat their vegetables. That night, my fever spiked close to 104, launching me into a kaleidoscope of fever dreams where my brain decided to give me the full surrealist experience. Words from my podcasts took on physical forms—spiky, sticky, grotesque shapes—and suddenly, I was inside them. I wandered through caves of conversation, waded through cocoons of dialogue, and got tangled in thick spider webs spun from language. Each sentence wrapped around me, trapping me in its endless loops of nonsense.

When I woke up, drenched in sweat and feeling like I’d wrestled a linguistically gifted tarantula, I realized the flu wasn’t just an illness—it was a full-blown avant-garde art installation happening in my own head. So no, I didn’t have food poisoning. I had performance art fever. And while it wasn’t the cabbage apocalypse I’d hoped for, it was plenty weird in its own way.

For six days, I had been wrestling with the so-called “Thanksgiving Flu,” a charming little virus that kept my fever bouncing between 101 and 104, as if my body were auditioning for a medical melodrama. Being that sick wasn’t just about physical misery—it was a battering ram smashing through the cozy little mental structures I had built around my life. Aspirations? Pointless. Health goals? A cruel joke. My reading list? Forget it. Even my hunger for social belonging and validation had been knocked flat. What remained was a stripped-down nihilism so bleak it made Nietzsche look like an optimist.

Sickness dragged me to a dark place where life felt like a cosmic prank. I could almost hear my 14-year-old self rolling his eyes as I remembered my Grandma Mildred’s wise words from one of her letters: “Illnesses bring out the doldrums.” No kidding, Grandma. That particular flu had brought out more than the doldrums—it had conjured a maudlin cocktail of despair and self-pity.

In that state, I found myself spiraling into melodrama, muttering things like, “What’s the point? Just end the torment and let me meet my Maker already!” It was ridiculous, of course, but I couldn’t help but notice how flu-induced misery fed into a distinctly male flavor of narcissism. Egotism, after all, was a hallmark of the man-child: the guy who thought the universe should pause when he didn’t get his way.

Men, it seemed, were uniquely gifted at turning minor discomforts into existential crises. While women powered through illness with a mix of stoicism and practicality, men turned their sickbeds into thrones of self-pity, proclaiming their impending doom to anyone who would listen. And me? I was no exception. With every feverish shiver, I became the star of my own overwrought drama, raging against the cruelty of a world that dared to continue spinning while I wallowed in flu-induced existential despair.

Sure, Grandma Mildred, the doldrums were part of the package—but why did it feel like men turned those doldrums into an art form? Perhaps the real flu virus wasn’t in my body; it was in my ego, throwing a tantrum because life wasn’t bending to my fevered will.

I appeared to be languishing in the Flu-tile State—a fever-fueled realization that all human endeavor was futile.

On day 8 of this flu from hell, my doctor emailed me a cheerful little grenade: “Your symptoms are concerning. I need to see you today.” Fabulous. At 11 a.m., feverish, grouchy, and radiating the energy of a half-cooked zombie, I dragged myself to her office for the usual poking and prodding. COVID? Negative. Influenza? Oh yes, Influenza A—the viral overachiever of the season. My nurse, who’d had it two weeks earlier, gave me the kind of pep talk you’d expect from someone who survived a minor apocalypse. “Seven days of fever,” she chirped, “so you’ve probably got two more to go!” Like I’d won a spa weekend in purgatory.

But the flu wasn’t the real sucker punch. No, that came when I stepped on the scale. At a soul-crushing 252 pounds, with blood pressure at 166 over 92, Dr. Okada laid it out with the dispassion of someone reading a menu: “You’re at high risk for a massive stroke or heart attack.” She might as well have handed me a shovel and a map to my future grave. Then, just to twist the knife, she added, “You need to lose fifty pounds in six months. Otherwise…” She trailed off, but I got the point: dead man waddling.

Her final blow came with a steely gaze and a guilt grenade: “If not for yourself, lose weight for your wife and daughters.” Translation: stop being selfish and get your act together before they have to plan your funeral.

Desperate for a cheat code, I asked about Mounjaro or Ozempic, those miracle weight-loss injectables I’d read about. She barely stifled a laugh. “We prescribe those for people with exclusive employer benefits.” I muttered something about how my college likely doesn’t cover luxury drugs, and her thin smile confirmed it. I’d be fighting this battle the old-fashioned way: with the DASH diet and restricted calories, not cutting-edge pharmaceuticals.

And then there was the Motrin ban. Apparently, my go-to painkiller was a blood-pressure ticking time bomb. “No more Motrin. Tylenol only,” she said, with all the enthusiasm of a waiter recommending the tofu option. So now, my fevers would be accompanied by a dull, Tylenol-soaked march toward mortality. Fantastic.

I thanked her—sincerely, I swear—because she wasn’t wrong. But the whole thing felt like I’d been blindsided by a particularly grim episode of The Biggest Loser: Medical Edition. On the drive home, Miley Cyrus’s “Flowers (Demo)” came on, and I—feverish, bloated, and thoroughly defeated—actually cried. Miley crooned about resilience and self-love, and all I could think about was how laxity, that slow, sneaky killer, had been working me over for years. Skipped workouts, mindless snacks, every excuse—it had all led to this: a middle-aged man sobbing in his car, mourning his dignity while stuck in traffic.

Dr. Okada’s tough love landed like a wrecking ball. This was my moment—the kind where you either turn your life around or start drafting your obituary. Time to put down the Motrin, pick up some discipline, and drag myself back from the brink before I became the subject of one of those tragic lessons everyone ignores until it’s too late cautionary tales.

I had entered the clinic expecting to get a quick flu diagnosis and maybe a lecture about rest and fluids. Instead, I walked out with the realization that my life wasn’t just off-track; it was an unmitigated dumpster fire rolling downhill. How had I missed it? The creeping wreckage of my existence had been unfolding right under my nose, like a slow-motion train derailment I refused to acknowledge. Denial, thy name is me.

Dr. Okada, bless her clinical professionalism, had held up a mirror and forced me to see what I’d been expertly avoiding for years: that my life, much like my blood pressure, was a ticking time bomb. I’d been blind to my own unraveling, and now the blinders were off. The view wasn’t pretty, but at least now I knew what I was working with—a fixer-upper existence in desperate need of a renovation.

My visit to the doctor turned into an unplanned catalyst for a long-overdue moral metamorphosis. I left not just diagnosed, but afflicted by a new condition I can only call the Scales of Justice (and Shame)—that peculiar state where the doctor’s scale transforms into the ultimate moral arbiter. Each number glaring back at me didn’t just measure pounds; it weighed my life choices, my discipline, my worthiness as a functioning adult. It was less a medical device and more a courtroom, and let’s just say I was found guilty on all counts.

I was convinced that had I been ten years older, this bout of influenza would have finished me off. The first week felt less like an illness and more like the aftermath of a roadside bombing, with me as the unfortunate bystander left mangled in a ditch. My body was a buffet for phantom wolves and mosquitoes—every nerve ending seemed to host its own ravenous pest. Mentally, I spiraled into fever-induced madness, complete with hallucinatory jungle scenes: Gumby-esque AI bodybuilders, sculpted and sinewy yet gelatinous, painted the revolting hue of yellow sea slugs, slithered around me in an Amazonian hellscape.

By Week Three, the influenza had mercifully downgraded its malevolence, though “mild” feels like an insult to language. I still shivered like a Victorian orphan in a snowstorm, my body temperature yoyoing between inferno and tundra. Aches gnawed at me persistently, like bad houseguests who don’t get the hint. And mentally? I was underwater—grasping at reality as it floats just out of reach. My brain felt stripped of a few critical screws, rattling around and threatening to unscrew the rest.

At some point, I recalled, in the hazy, fevered way of someone stranded in a desert, that my daughter had lozenges in her room. Fueled by desperation, I shuffled to her door, knocked weakly, and thrust my trembling hands forward as if auditioning for a Dickens adaptation. “Please,” I croaked, my voice barely above a whisper, “fill my hands with lozenges for your poor ailing father.”

The response? Hysterical laughter. Both of my daughters, cozied up watching TV, howled with the kind of delight usually reserved for viral cat videos. I caught a glimpse of myself in the hallway mirror: pajamas wrinkled like a bad alibi, beanie perched jauntily askew, my face the pallor of a sickly sailor. I was every bit the tragicomic figure they saw—a fevered street urchin begging for cough drops.

My wife, ever the realist, stormed in to restore order. “We have plenty of lozenges in the kitchen,” she barked, clearly unimpressed by my Oscar-worthy theatrics. She led me, limping and pathetic, to the cupboard, where she proceeded to dump several bags of lozenges onto the table with all the ceremony of Santa Claus unloading his sleigh. My daughters, tears of laughter streaming down their faces, declared me Oliver Twist reincarnated.

I retreated to bed clutching a handful of lozenges, humiliated but momentarily soothed, only to lie awake wondering when this fever would break—or if the AI bodybuilders would show up again to finish the job.

Four weeks into my bout with influenza, I emerged bleary-eyed, fever-wrecked, and staring down my old nemesis: addiction. Not the sexy kind you’d brag about in a memoir—just the creeping, mundane kind that comes with a tendency to overindulge in things like self-pity, compulsive behaviors, and yes, an irrational attachment to writing books.

And so, I emerged from this fever-ridden odyssey not as a transformed man, but as someone who had simply suffered enough to pause and reflect—until the next catastrophe beckoned. If John Bradshaw were leading my recovery workshop, he’d likely hand me a stuffed animal and instruct me to embrace my inner child, soothing my cabbage-traumatized soul with affirmations of self-love. But after weeks of sweating, hallucinating, and contemplating my own obituary over a bag of rotting vegetables, I didn’t need a teddy bear. I needed a referee, a financial adviser, and possibly an exorcist.

The true lesson here? My inner child doesn’t need rescuing. He needs a restraining order. Because left to his own devices, he’ll continue to eat spoiled food out of spite, spiral into existential despair at the first sign of adversity, and demand that every brush with mortality be converted into premium content. So if I’m to move forward as a recovering writing addict, I have to acknowledge this truth: The inner child is not a sage. He’s a lunatic. And I should probably stop taking his advice.

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX

As part of my rehabilitation from writing novels I have no business writing, I remind myself of an uncomfortable truth: 95% of books—both fiction and nonfiction—are just bloated short stories and essays with unnecessary padding. How many times have I read a novel and thought, This would have been a killer short story, but as a novel, it’s a slog? How often have I powered through a nonfiction screed only to realize that everything I needed was in the first chapter, and the rest was just an echo chamber of diminishing returns?

Perhaps someday, I’ll learn to write an exceptional short story—the kind that punches above its weight, the kind that leaves you feeling like you’ve just read a 400-page novel even though it barely clears 30. It takes a rare kind of genius to pull off this magic trick. I think of Alice Munro’s layered portraits of regret, Lorrie Moore’s razor-sharp wit, and John Cheever’s meticulous dissections of suburban despair. I flip through my extra-large edition of The Stories of John Cheever, and three stand out like glittering relics: “The Swimmer,” “The Country Husband,” and “The Jewels of the Cabots.” Each is a self-contained universe, a potent literary multivitamin that somehow delivers all the nourishment of a novel in a single, concentrated dose. Let’s call these rare works Stories That Ate a Novel—compact, ferocious, and packed with enough emotional and intellectual weight to render lesser novels redundant.

As part of my rehabilitation, I must seek out such stories, study them, and attempt to write them. Not just as an artistic exercise, but as a safeguard against relapse—the last thing I need is another 300-page corpse of a novel stinking up my hard drive.

But maybe this is more than just a recovery plan. Maybe this is a new mission—championing Stories That Eat Novels. The cultural winds are shifting in my favor. Attention spans, gnawed to the bone by social media, no longer tolerate literary excess. Even the New York Times has noted the rise of the short novel, reporting in “To the Point: Short Novels Dominate International Booker Prize Nominees” that books under 200 pages are taking center stage. We may be witnessing a tectonic shift, an age where brevity is not just a virtue but a necessity.

For a failed novelist and an unapologetic literary wind-sprinter, this could be my moment. I can already see it—my sleek, ruthless 160-page collection, Stories That Eat Novels, four lapidary masterpieces gleaming like finely cut diamonds. Rehabilitation has never felt so good. Who says a man in his sixties can’t find his literary niche and stage an artistic rebirth? Maybe I wasn’t a failed novelist after all—maybe I was just a short-form assassin waiting for the right age to arrive.