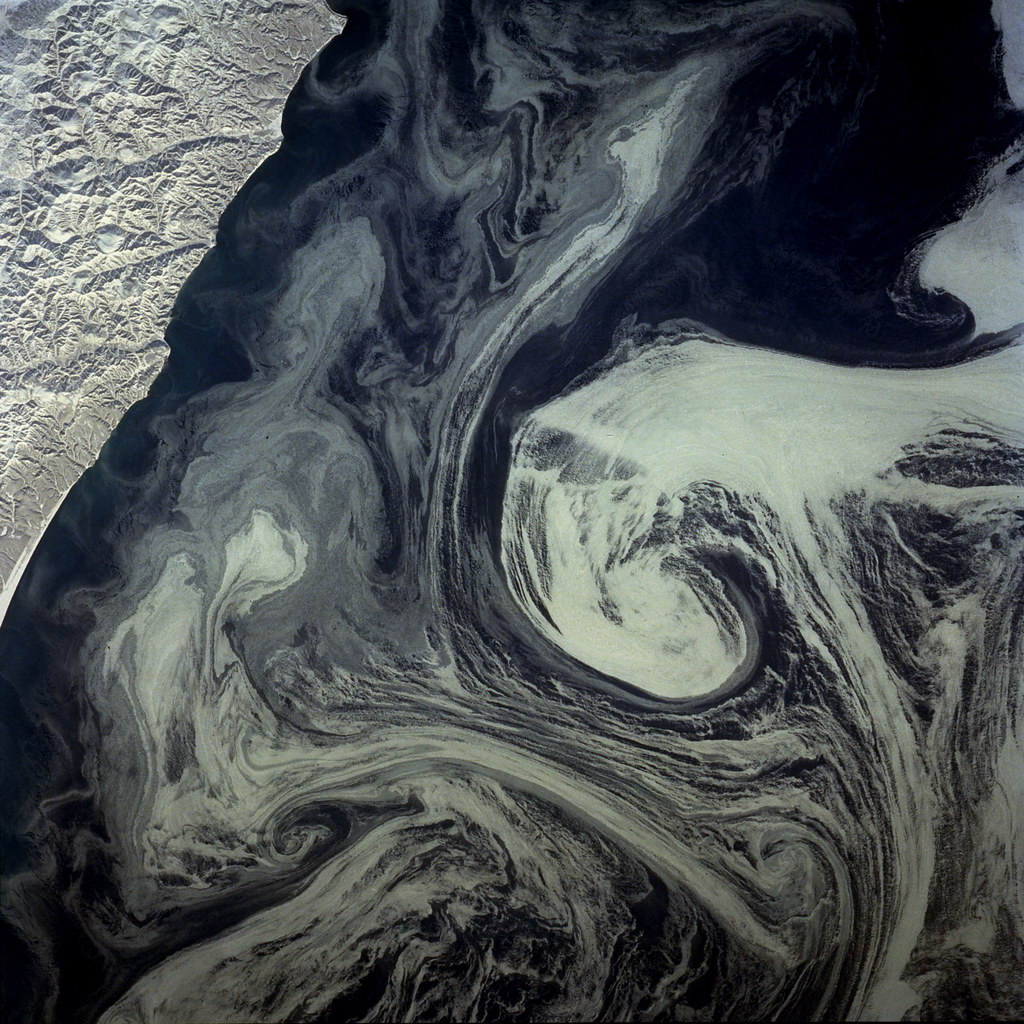

It’s wired into the species—not just the desire to belong, but the craving to belong intensely, to slip past the outer ring of acquaintances and take a seat inside the inner ring, the secret hearth where the real warmth allegedly lives. Decades ago, I convinced myself I had secured that coveted spot within my friend group. Then came the day I wasn’t invited to what I imagined was a grand, festive gathering. One tiny exclusion detonated my entire reality. I felt betrayed, humiliated, and terrified. Had I been exiled? Had I never belonged at all? What kind of fool mistakes polite laughter for fellowship? The hurt settled in for years. I saw myself as a wounded wolf limping away from the pack, nipped at the heels, slipping into the freezing brush alone—shivering, haggard, staring back at the others as I wondered what was left for me now.

Three decades later, the story has taken on different contours. If I’m honest, I suspect I was never part of anyone’s inner circle; I was the victim of my own wishcasting. My glum tendencies—funny in small doses, exhausting in larger ones—probably nudged me to the periphery from the start. And in a twist more humbling than any imagined exile, I eventually learned the friend group didn’t have an inner circle at all. After one member retired, another admitted they rarely saw each other, that their camaraderie had been built on workplace convenience, not tribal loyalty. My grand narrative of being cast out by a cabal of insiders evaporated. There had been no cabal—just ordinary friendships and my own melodramatic imagination.

So now the task is simple and difficult at once: forgive myself for the fears and delusions that shaped the story. Reclaim myself. Return to the only inner circle that was ever guaranteed—my own. Maybe that hunger for return is the quiet power of religion: the promise that we can wander, fall apart, and still be welcomed home. The myth of my “expulsion from the inner circle” now feels biblical in scale, a parable of longing not just for belonging, but for wholeness, acceptance, and the grace of being taken back as I am.