In my Critical Thinking course, we tackle three research-based essays that wrestle with one central, disquieting premise: technology is not just helping us live—it’s rewriting what it means to be human. Our first unit? A polite but pointed takedown of the American weight loss gospel. The assignment is called The Aesthetic Industrial Complex, and it asks students to write a 1,700-word argumentative essay exploring a question that’s fast becoming unavoidable: Does the old moral framework of discipline, kale, and “personal responsibility” still hold water in the age of GLP-1 injections, food-delivery algorithms, and weaponized Instagram bodies?

We dive into the stories of good-faith dieters—folks who’ve counted calories, logged cardio, avoided sugar like it was plutonium—and still watched their doctors frown over charts lit up with prediabetes, high blood pressure, and the telltale signs of metabolic collapse. These are not cases of vanity. These are mandates from cardiologists and endocrinologists. Lose weight or lose time.

Enter the needle. GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy promise what decades of dieting books never delivered: chemical satiety and the end of food noise—that constant mental hum that turns the pantry into a siren song. The results are seismic: hunger down, weight down, cravings down, existential questions up.

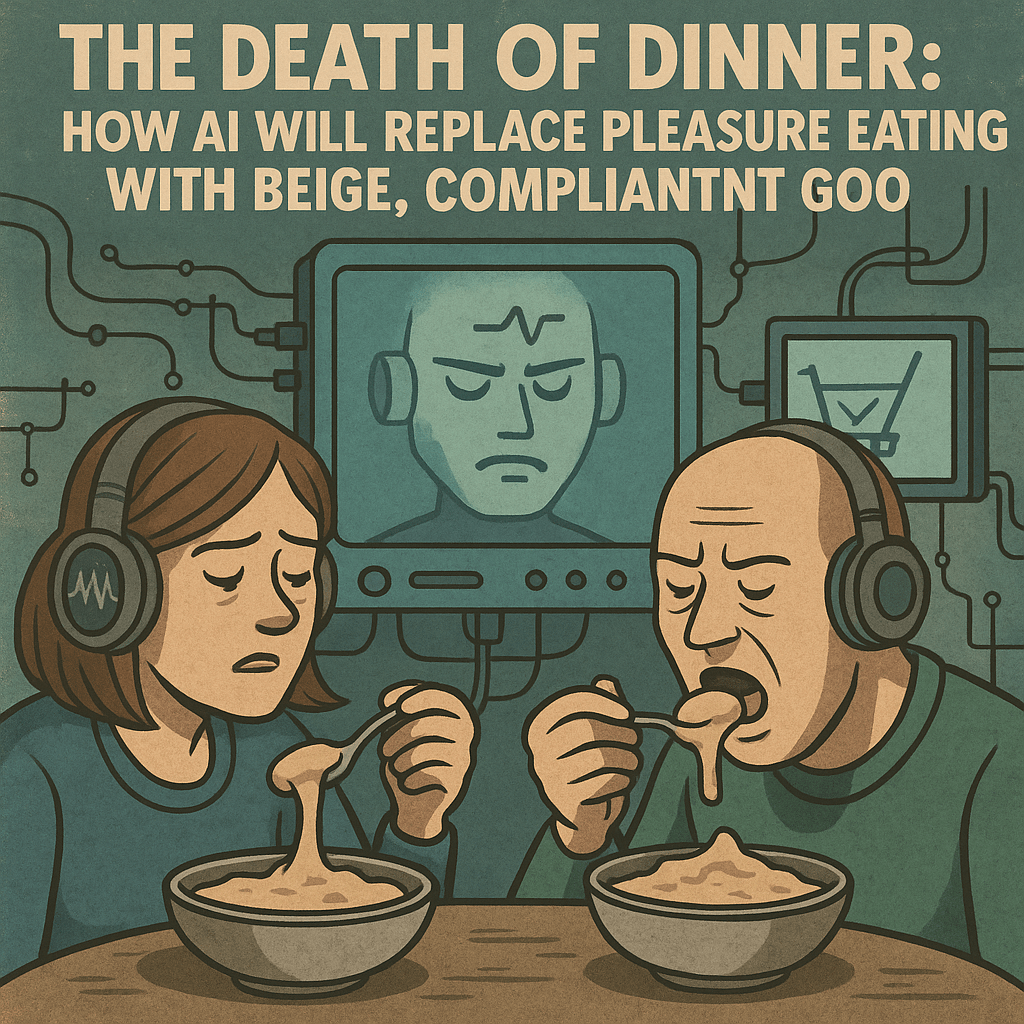

Because here’s the paradox: when food no longer seduces us, we gain a body that’s marketable and medically optimized—but we lose something else. Food is not just fuel. It’s ritual. It’s celebration. It’s Grandma’s lasagna, a first date over sushi, a kitchen filled with the smell of garlic. Food is culture, memory, and soul. And yet, being ruled by it? That’s a kind of servitude. Constant hunger is its own form of imprisonment.

So we’re caught in a new paradox: to be free from food, we must become dependent on pharmacological salvation. Health insurers love it. Employers love it. Actuarial tables are singing hymns of praise. But should we?

That’s the real assignment: not just whether GLP-1s work, but whether the shift they represent is something to embrace or fear. This is no clear-cut debate. It’s a riddle with contradictory truths. A tug-of-war between biology, economics, ethics, and the shrinking silhouette in the mirror.

And if my students groan under the weight of the question, I remind them: this isn’t Home Ec. This is Critical Thinking. If you want easy answers, go back to diet TikTok.