A few nights ago, I watched Big Vape: The Rise and Fall of Juul, the four-part autopsy of a company that promised salvation from combustible cigarettes and instead managed to hijack a generation’s taste buds. Juul framed itself as a public-health crusader. What it actually built was a sleek delivery system for addiction, turbocharged by flavors engineered to lodge themselves deep in the dopamine circuitry of young brains.

Former employees and users all pointed to the same thing: mango. Mango wasn’t just a flavor; it was an event. People didn’t vape mango casually. They marinated in it. Mango was the hook.

Watching this, I was transported back to my own childhood and my first chemical romance: Cap’n Crunch.

There was something about that unholy alliance of corn flour, palm oil, and brown sugar that short-circuited my will. I didn’t want moderation; I wanted saturation. My parents imposed limits, which only deepened my resolve to grow up as fast as possible so I could make my own enlightened dietary decisions—namely, Cap’n Crunch for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I failed to notice the irony that a grown man subsisting on sugar cereal would represent not maturity but infantilization.

Cap’n Crunch’s true genius wasn’t just sweetness. It was proliferation. The same cereal reappeared in endless costumes—Crunch Berries, Peanut Butter Crunch—each one offering the illusion of choice. King Vitamin was the most audacious iteration: Cap’n Crunch in a health halo, a masterclass in rebranding junk as virtue. Lipstick on a pig, poured into a cereal bowl.

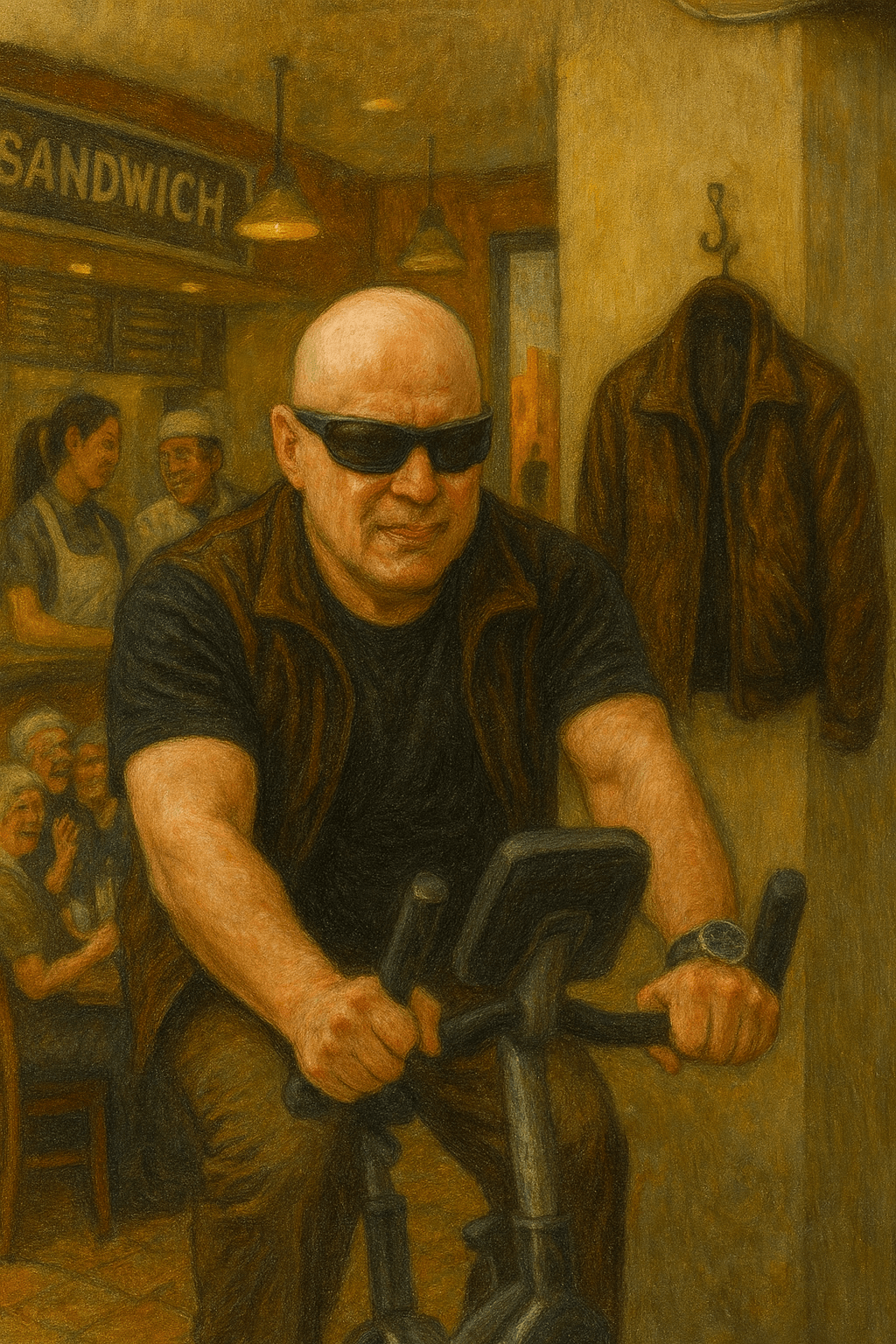

Then there were the mascots. Quisp the Martian. Quake the muscle-bound coal miner. As a child steeped in superhero comics and Hulk fantasies, I gravitated toward Quake. Strength. Power. Identity. I didn’t realize I was choosing a brand avatar, not a breakfast.

Cereal companies were having a field day. We watched cartoons while eating the very product being advertised between scenes. It never occurred to us that we were being conditioned—trained to celebrate a non-nutritive food substance that dissolved teeth and rewired appetite. The Juul kids didn’t know it either. They thought they were buying into a sleek, adult lifestyle. What they were really purchasing was dependence, with a mango aftertaste.

What troubles me now is that adults don’t seem any less susceptible.

Today, many people consume political tribes the way we once consumed sugar cereal and flavored vapor. Politics has been repackaged as lifestyle branding—complete with slogans, merch, cosplay, and dopamine hits. The substance is thin. The stimulation is constant. Critical thinking is nowhere to be found.

These aren’t political commitments; they’re identity snacks. Sugar rushes masquerading as convictions. Defense of one’s “views” consists of chanting talking points with the same reflexive loyalty I once reserved for Cap’n Crunch. No wonder the country feels like it’s in free fall. We haven’t grown up—we’ve just swapped mascots.

We are a nation of adult children, hooked on political flavors the way kids were hooked on cereal and Juul users were hooked on mango. Politics has become a consumer product: addictive, polarizing, shallow, and wildly profitable. All dopamine. No nutrition.