Thomas Chatterton Williams takes a scalpel to the latest mutation of social-media narcissism in his essay “Looksmaxxing Reveals the Depth of the Crisis Facing Young Men,” and what he exposes is not a quirky internet fad but a moral and psychological breakdown. Looksmaxxing is decadence without pleasure, cruelty without purpose, vanity stripped of even the dignity of irony. It reflects a culture so hollowed out that aesthetic dominance is mistaken for meaning and beauty is treated as a substitute for character, responsibility, or thought.

I first encountered the term on a podcast dissecting the pronouncements of an influencer called “Clavicular,” who dismissed J.D. Vance as politically unfit because of his face. Politics, apparently, had been reduced to a casting call. Vote for Gavin Newsom because he’s a Chad. At first, this struck me as faintly amusing—Nigel Tufnel turning the cosmetic dial to eleven. Williams disabuses us of that indulgence immediately. Looksmaxxing, he writes, is “narcissistic, cruel, racist, shot through with social Darwinism, and proudly anti-compassion.” To achieve their idealized faces and bodies, its adherents break bones, pulverize their jaws, and abuse meth to suppress appetite. This is not self-improvement. It is self-destruction masquerading as optimization, a pathology Williams rightly frames as evidence of a deeper moral crisis facing young men.

Ideologically, looksmaxxers are incoherent by design. They flirt with right-wing extremism, feel at home among Groypers, yet will abandon ideology instantly if a rival candidate looks more “alpha.” Their real allegiance is not conservatism or liberalism but Looksism—a belief system in which aesthetics trump ethics and beauty confers authority. Williams traces the movement back to incel culture, where resentment and misogyny provide a narrative to explain personal failure. The goal is not intimacy or community but status: to climb the visual pecking order of a same-sex digital hive.

At the center of Williams’ essay is a quieter, more unsettling question: what conditions have made young men so desperate to disappear into movements that erase them? Whether they become nihilistic looksmaxxers or retreat into rigid, mythic religiosity, the impulse is the same—to dissolve the self into something larger in order to escape the anxiety of living now. As Williams notes, this generation came of age online, during COVID, amid economic precarity, social fragmentation, and the reign of political leaders who modeled narcissism and grifting as leadership. Meaning became scarce. Recognition became zero-sum.

Williams deepens the diagnosis by invoking John B. Calhoun’s infamous mouse-utopia experiment. In conditions of peace and abundance, boredom metastasized into decadence. A subset of male mice—“the beautiful ones”—withdrew from social life, groomed obsessively, avoided conflict, and stopped reproducing. Comfort bred collapse. Beauty became a dead end. Death by preening. These mice didn’t dominate the colony; they hollowed it out. NPCs before the term existed.

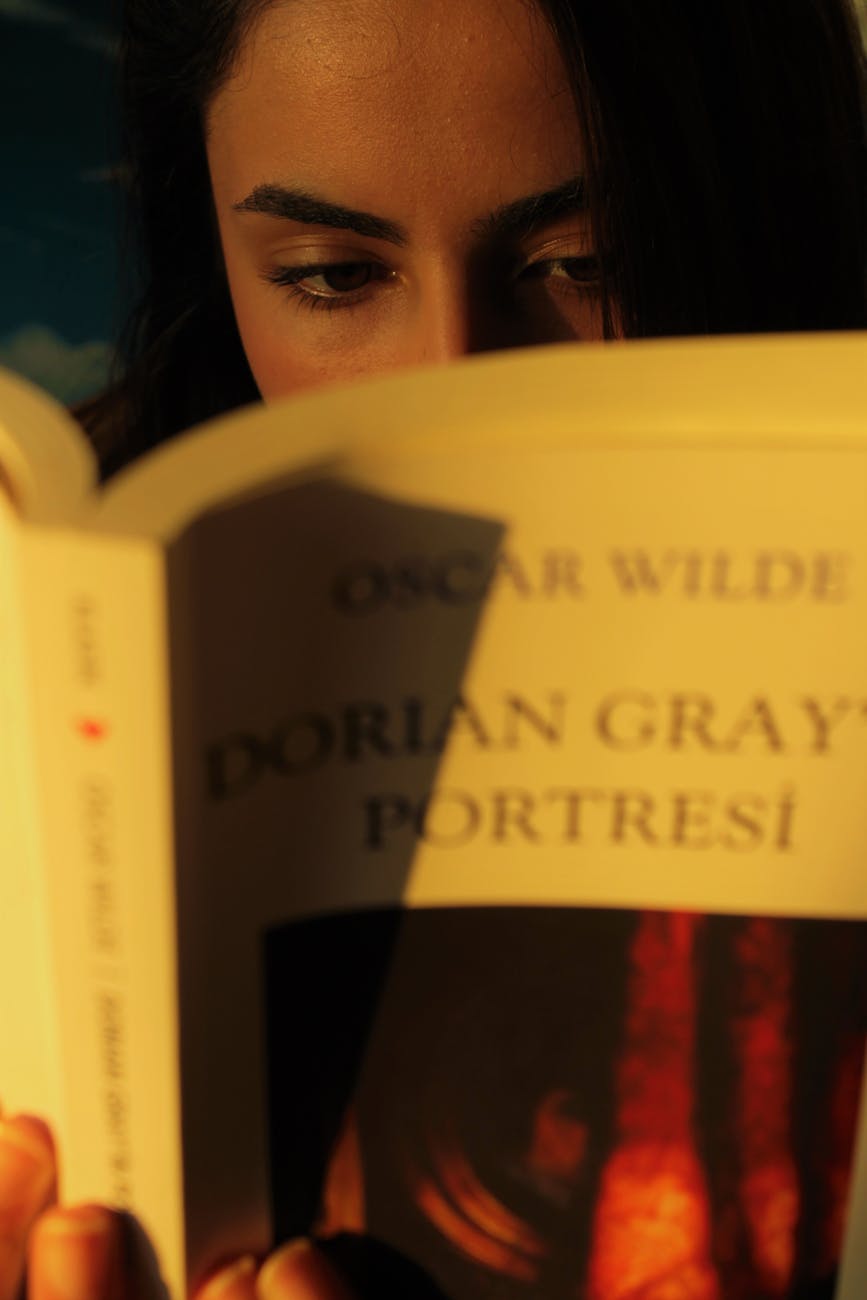

The literary echo is unmistakable. Williams turns to Oscar Wilde and The Picture of Dorian Gray, where beauty worship corrodes the soul. Wilde’s warning is blunt: the belief that beauty exempts you from responsibility leads not to transcendence but to ruin. Dorian’s damnation is not excess pleasure but moral vacancy.

The final irony of looksmaxxing is that it produces no beauty at all. The faces are grotesque, uncanny, AI-slicked, android masks stretched over despair. Their ugliness is proportional to their loneliness. Reading Williams, I kept thinking of a society fractured into information silos, starved of trust, rich in spectacle and poor in care—the perfect compost for a movement this putrescent. Looksmaxxing is not rebellion or politics. It’s a neglected child acting out. Multiply that child by millions and you begin to understand the depth of the crisis Williams is naming.