As I clawed my way out of my addiction to writing doomed novels (which were really short stories in disguise), a strange thing happened: buried emotions clawed back. It wasn’t pleasant. It was like peeling off a bandage only to discover that underneath was raw, exposed nerve endings. Turns out, the grandiose fever dream of writing had insulated me from reality. Now, stripped of that delusion, I was left unprotected, vulnerable, and completely awake to the world.

And the world, in 2025, was on fire.

Literally. The Los Angeles wildfires turned the sky into an apocalyptic hellscape—a choking haze of smoke and fury. The inferno forced me into an act I hadn’t performed in years: I dusted off a radio and tuned into live news.

That’s when I had two epiphanies.

First, I realized I despise my streaming devices. Their algorithm-fed content is an endless conveyor belt of lukewarm leftovers, a numbing backdrop of curated noise that feels canned, impersonal, and utterly devoid of gezelligheid, a sense of shared enjoyment. Worst of all, streaming had turned me into a passive listener, a zombie locked inside a walled garden of predictability. I spent my days warning my college students about AI flattening human expression, yet here I was, letting an algorithm flatten my own relationship with music.

But the moment I switched on the radio, its warmth hit me like an old friend I hadn’t seen in decades. A visceral ache spread through my chest as memories of radio’s golden spell came rushing back—memories of being nine years old, crawling into bed after watching Julia and The Flying Nun, slipping an earbud into my transistor radio, and being transported to another world.

Tuned to KFRC 610 AM, I was no longer just a kid in the suburbs—I was part of something bigger. The shimmering sounds of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Hot Fun in the Summertime” or Tommy James and the Shondells’ “Crystal Blue Persuasion” weren’t just songs; they were shared experiences. Thousands of others were listening at that same moment, swaying to the same rhythms, caught in the same invisible current of sound.

And then I realized—that connection was gone.

The wildfires didn’t just incinerate acres of land; they exposed the gaping fault lines in my craving for something real. Nostalgia hit like a sucker punch, and before I knew it, I was tumbling down an online rabbit hole, obsessively researching high-performance radios, convinced that the right one could resurrect the magic of my youth.

But was this really about better reception?

Or was it just another pathetic attempt to outrun mortality?

Streaming didn’t just change my relationship with music; it hollowed it out.

I had been living in a frictionless digital utopia, where effort was obsolete and everything was available on demand—and I was miserable. Streaming devices optimized convenience at the cost of discovery, flattening music into algorithmic predictability, stripping it of its spontaneity, and reducing me to a passive consumer scrolling through pre-packaged soundscapes.

It was ironic. I had let technology lull me into the very state of mediocrity I warned my students about.

Kyle Chayka’s Flatworld spells out the horror in precise terms: when you optimize everything, you kill everything that makes life rich and rewarding. Just as Ozempic flattens hunger, technology flattens culture into a pre-digested slurry of lifeless efficiency.

I didn’t need Flatworld to tell me this. I had lived it.

The day I flipped on a real radio again, I didn’t just hear a broadcast—I heard my brain rebooting. The warmth, the spontaneity, the realness of people talking in real time—it was the sonic equivalent of quitting Soylent and biting into a perfectly seared ribeye.

If Flatworld taught me anything, it’s that aliveness is exactly what convenience culture is designed to eradicate.

Once I abandoned streaming, I filled every room in my house with a high-performance multiband radio. My love of music returned. A strange peace settled over me.

The problem? My addictive personality latched onto radios with a zeal that bordered on the irrational.

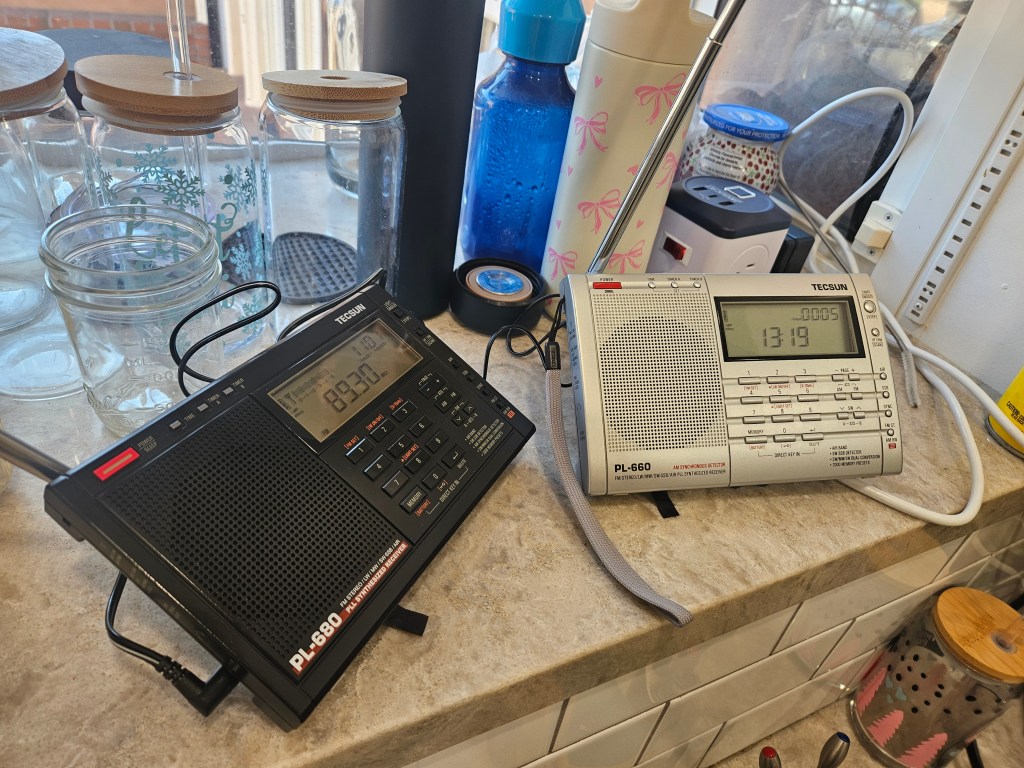

I began gazing at them with the kind of reverence normally reserved for religious icons. When I spotted a Tecsun PL-990, PL-880, PL-680, or PL-660, something in my brain short-circuited. I was instantly enchanted, as if I had just glimpsed an old friend across a crowded room. At the same time, I was comforted, as if that friend had handed me a warm cup of coffee and told me everything was going to be alright.

But a radio isn’t just a device. It’s a symbol, though I’m still working out of what exactly.

Maybe it represents the lost art of slowing down—of sitting in a quiet room, wrapped in a cocoon of music or familiar voices. Or maybe it’s something deeper, a sanctuary against the relentless noise of modern life, a frequency through which I can tune out the profane and tune into something sacred.

The word that comes to mind when I hold a radio is cozy—but not in the scented-candle, novelty-mug kind of way. This is something deeper, something akin to the Dutch word gezelligheid—a feeling of warmth, belonging, and ineffable connection to the present moment.

Radios don’t just play sound; they create atmosphere. They transport me back to Hollywood, Florida, sitting on the porch with my grandfather, the air thick with the scent of an impending tropical storm, the crackle of a ball game playing in the background like the heartbeat of another era.

That’s the thing about gezelligheid—it isn’t something you can program into an algorithm. It isn’t something you can optimize. It’s a byproduct of presence, community, and shared experience—the very things convenience culture erodes.

Many have abandoned radio for the cold efficiency of streaming and smartphones.

I tried to do the same for over a decade.

I failed.

Because some things, no matter how old-fashioned, still hum with life.

And maybe that’s what replacing streaming devices with radios is about—not just recovering from my addiction to writing abysmal novels, but recovering life itself from the grip of Flatworld.