In 1984, while you were still in college, your grandfather—a card-carrying Marxist who frequented Russia and Cuba and claimed to have befriended Fidel Castro—decided to pay your way for a Soviet-sponsored “Sputnik Peace Tour.” He wanted you to see the Soviet Union through his rose-colored glasses. Maybe, just maybe, you’d come home singing the Soviet anthem with a crimson flag tattoo stretched across your 52-inch chest.

You joined a group of about a dozen college students from across the country, a few professors from Arkansas and Tennessee, and a Soviet-appointed tour guide named Natasha. The plan was to travel mostly by train—from Moscow to Kyiv, Odessa, Novgorod, Leningrad, and back to Moscow.

To prep you for the two-week summer adventure, your grandfather handed you a copy of Mike Davidow’s Cities Without Crisis: The Soviet Union Through the Eyes of an American. According to Davidow, the USSR was a society in bloom—happy children with “rose-colored cheeks” played in utopian cities unblemished by the chaos and violence of capitalist America.

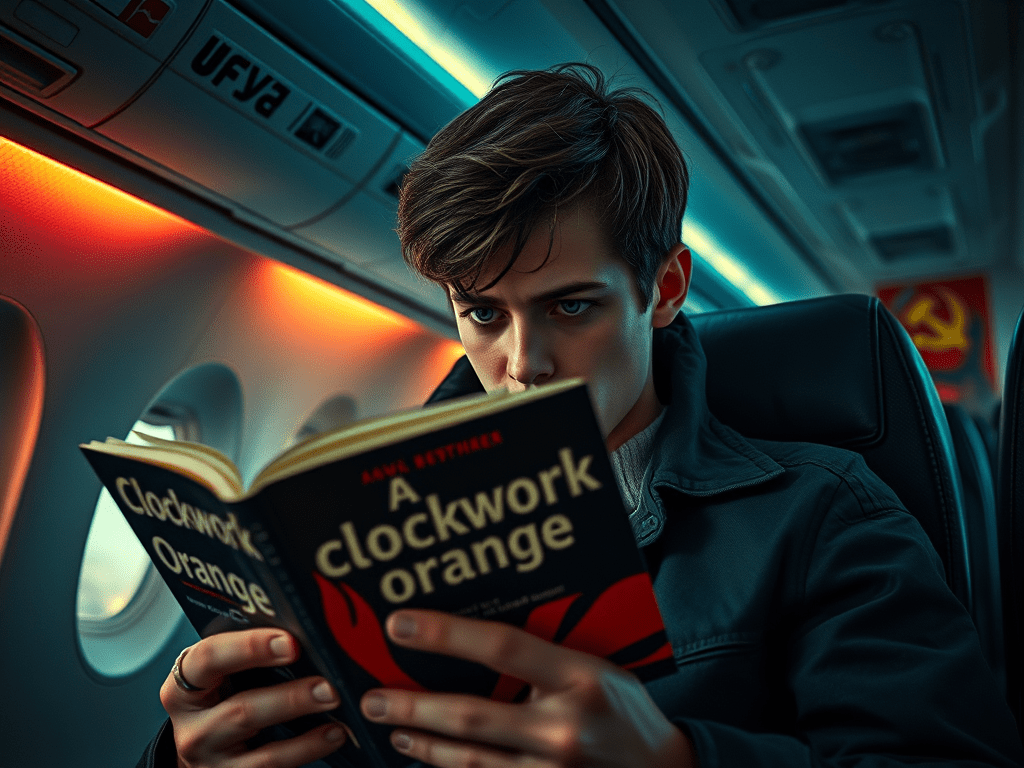

Out of gratitude, you gave the book a fair chance. But by the halfway point, the propaganda wore you down. It was a slog—repetitive, dull, and deaf to irony. You ditched Davidow for A Clockwork Orange, a dystopian acid bath from Anthony Burgess that, had your grandfather caught you reading it, would’ve gotten you labeled a reactionary.

You carried that subversive novel on the Aeroflot flight from New York to Moscow. That’s when Jerry Gold—a fellow tourist and law student at Brown—noticed it and leaned in with a warning: “They’ll probably confiscate that at the airport,” he said. “They’ll mark you as a troublemaker and keep tags on you. Look over your shoulder. And if anyone offers you good money for your jeans, it’s probably KGB. Black-market trading will land you in prison.”

You laughed nervously, but the real threat onboard was not the KGB—it was the in-flight food. Small foil-wrapped cheeses, off-color cold cuts, wilted lettuce, and soggy carrot slices—all served by demure flight attendants in drab uniforms. The Aeroflot menu was a direct contradiction to Davidow’s utopia. A lack of good food was a crisis, and pretending otherwise was its own crisis.

Jerry, peeling the foil off his sad cheese triangle, folded his industrial-grade napkin and pocketed it. “This might be the only toilet paper you get on this trip,” he advised.

“That’s disgusting.”

“You ever used an Eastern European toilet?”

You hadn’t.

“A hole in the ground. Deep knee bend. Free Jack LaLanne workout. Things can be primitive.”

You asked why, with all his doom-saying, he’d signed up.

“College credit. Exotic street cred. How many Americans get to say they’ve been to the USSR?” He bit his cheese like it was a dare. “What about you?”

“My grandfather wants to convert me. He’s a communist.”

“So he sent you to paradise.” Jerry pinched a cold cut and gave it a good stare.

“The food’s not a winning argument,” you said. “Neither is the lack of toilet paper.”

Jerry smirked. “In the Soviet Union, if you see a line, you stand in it. It means something’s for sale.”

A week later, you stood sweating in a Kyiv market watching babushkas queue for wrinkled, fly-covered chickens. You thought, Cities without crisis? Bullshit. Sixty-two miles away sat Chernobyl. Two years later, the reactor would blow. Cities without crisis indeed.

But in 1984, as you encountered shortages, queues, and squat toilets, one detail stirred something close to admiration: classical music playing everywhere—train stations, parks, museums. Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Prokofiev streamed from speakers like sonic incense. Was it cultural enrichment or state-sponsored propaganda—a rebuke to Western vulgarity? You wanted to believe it was the former. Your grandfather would’ve insisted it was.

No one confiscated your Burgess novel at the airport, but the following day, at the Moscow Zoo, you saw a silverback gorilla pounding his chest while a Rachmaninoff piano piece played. Then she appeared: a stunning woman in an elegant black dress, black hat, and pearls. She smiled and told you, “You look very Russian.”

She wasn’t wrong. Your mother’s family hailed from Belarus and Poland. Even your fellow tourists said you looked native. She added, “Russian men are strong. You are weightlifter, yes?”

You were. Before bodybuilding, you’d competed in Olympic weightlifting and idolized Vasily Alekseyev.

“Russian women love strong men,” she purred.

You blushed and beamed. Then Natasha grabbed your arm and marched you behind some bushes. She said the woman was probably KGB. A honey trap. Kompromat. Whatever the game was, Natasha wanted it shut down.

But you couldn’t stop thinking about her. You had been awkward and monkish in college, more comfortable with piano, Nietzsche, and protein powder than dating. Now you felt unshackled, lusty, hungry for connection. Natasha had ruined your chance—or so you believed.

The next morning, you found a grand piano in the lobby of the Moscow Olympic Hotel. You played a sad piece you’d composed. Your fellow tourists gathered, impressed. Truth was, you were a sloppy pianist who overcompensated with melodrama. But you had flair.

At a nearby table, Soviet military officers drank warm beer. The Commander—tall, square-jawed, festooned in medals—watched you. Then you saw her again: the woman from the zoo, standing by the piano. Before you could approach her, the Commander locked eyes with her, leered, and sent her fleeing.

He turned to you and mimicked your piano-playing with theatrical finger waggles. His men laughed. He invited you to his table, poured you warm beer, and barked, “Drink!”

Three times he commanded. You complied. It was the price of being a charlatan. A dandy. A fraud. Russians trained their children in piano. You were a ham with no chops. He knew. They all knew.

When you got back to your room and twisted the sink’s cold-water knob, the entire unit came off the wall and slashed your chest. You bled, cursed, and lifted your shirt the rest of the day to show off your injury as proof that Russia itself was trying to kill you.

The Commander popped up again—on the train to Novgorod. He laughed when he saw you. Jerry speculated he was keeping tabs on you. CIA paranoia, or just Soviet protocol?

You weren’t sure. But by the time you arrived in Novgorod, you had a fever. Natasha insisted on a doctor. Soon, a stunning, no-nonsense woman in a white coat examined you, declared it a cold, and ordered you to drop your pants for a Soviet “remedy.”

The shot felt like hot tar. Your fellow tourists watched, delighted.

At a barn lecture the next day, the Commander showed up again, reinforcing that you were always being watched. Jerry managed to prank him with a piece of hay, brushing his neck like a mosquito. The Commander slapped himself silly. Your group stifled laughter. You limped away, your ass sore, your ego tattered.

Later, at a toy factory near the forest, you saw buses of children arriving. When you asked Natasha if they were starting a shift, she had them shooed away. One boy even got a boot to the backside. You had glimpsed a truth they didn’t want captured.

That night, North Korean kids in uniforms got the best dinner service at the hotel. You and your group got leftovers, like stray dogs. You were done with Novgorod. You needed Leningrad.

The next evening, you were sitting in a Leningrad discotheque, still nursing a sore ass, and talking to a cute Finnish girl named Tula. It turned out you had a lot in common. You were both in your early twenties. You both shared a passion for Russian literature and the music of Rachmaninoff. As you conversed under the glittering gold disco ball, the Bee Gees’ “Too Much Heaven” blared across the club. Through your mutual confessions, it became clear that neither of you had any real romantic experience. Tula was short, diminutive, bespectacled, and elfin, with short sandy blond hair. At one point, she said, “I will never marry. I have, what do you say in English? Melancholy. Yes, I have melancholy. You know this word?”

“Yes, I was no stranger to melancholy,” you said.

“I am so much like that,” she told you.

“That explains your love of Rachmaninoff,” you said.

She clasped her hands and almost became teary-eyed. “How I love Rachmaninoff. Just utter his name, and I will break down weeping.”

You thought you were a depressive, but in the presence of Tula, you had the perkiness of Richard Simmons leading an aerobics class.

She asked what you were doing in Russia. You explained that your grandfather was a card-carrying communist, a friend of Fidel Castro, and a supporter of the Soviet Union. He used a shortwave radio in his San Pedro house to communicate with Soviet sailors on nearby ships and submarines. He visited Cuba whenever he could, bringing medical supplies that were in demand. One of his friends, a Hollywood writer, had lived in exile in Nicaragua after being arrested in France by Interpol for driving a Peugeot station wagon filled with illegal weapons. Your grandfather had wanted you to fall in love with the Soviet Union and become a champion of its utopian vision, so he paid for you to go on a peace tour.

Had you fallen in love with Russia the way your grandfather had hoped? Not really. So far, you had been approached at the Moscow Zoo by a striking woman in black and pearls—whom Natasha, your tour guide, claimed was a KGB agent trying to frame you for soliciting a prostitute. You had been washing your hands at the newly built Olympic Hotel in Moscow when the sink fell out of the wall and gashed your torso. You’d caught a fever in Novgorod, prompting a beautiful, stern-faced doctor to give you a shot in the ass. You’d been approached by young men on the subway asking if you wanted to sell your American jeans—just as Jerry Gold had warned—most likely a KGB setup for black-market entrapment. And everywhere you went—hotels, trains, restaurants—grim chamber music poured from loudspeakers, as if the Soviet authorities were saying, “Try not to be too happy while you’re here.”

Tula listened to your long-winded tale for a couple of hours, wide-eyed, touching your shoulder. “I need to see you again,” she said.

You agreed to meet the next day at the Peterhof Royal Palace by the Samson Fountain. The place was enormous—a garden the size of multiple football fields, full of gold statues and fountains shooting jets of water into the air. You and Tula sat on the hot concrete steps in the near-ninety-degree heat, flanked by golden naked statues posed around a spectacle known as the Grand Cascade. She wore a short white dress. Eventually, the heat got to you both, and you decided to get ice cream.

On your way to the ice cream bar, a gypsy suddenly tried to hand you a baby—like a quarterback executing a handoff. Before the infant could land in your arms, a Russian police officer swooped in, seized the baby, returned it to the gypsy, and shouted at her. You thought for sure she’d be arrested, but the officer merely berated her. She shriveled under the scolding and slinked away with the child.

You returned to Tula with the ice cream and recounted the bizarre scene.

She nodded. “Things like that happen all the time here.”

“But what was I supposed to do with the baby?”

“Perhaps adopt it? Buy it? Save it from a life of misery? There is so much tragedy here.”

“So I was supposed to fly back to the States with a baby? Go through customs and everything?”

“I know. It’s crazy.”

“I don’t think I could be a parent. I don’t have the hardwiring for it.”

“Me either. I’m too sad to be a parent. Sadness is a full-time job that leaves me with little energy for much else.”

She finished her ice cream and smiled at you, then said, “You and I are like two kindred spirits meeting each other in this strange world.”

“It’s hotter than hell out here,” you said.

“So will you marry someday?”

You shrugged. “I doubt anyone will take me.”

“Don’t be so hard on yourself. If I were the marrying type, I would come to America and spend my life with you. We could live in California and be sad together. Wouldn’t that be lovely?”

And oddly, it did sound lovely—living in shared sadness with Tula, marinating in Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony, discussing the existential torment of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. What other kind of life was there?

She stood up and said she had to catch her plane back to Finland. She gave you a chaste kiss on the cheek.

“I really hope you find happiness. You are such an outstanding person.”

“Outstanding?” you repeated, unable to hide your skepticism. The word struck you as hollow—like describing a house beside train tracks as “charming.” You echoed the adjective with a trace of sarcasm and said goodbye. You never saw her again, but you never forgot the vanilla ice cream—it remained the best you’d ever tasted.

Nine months later, you were back in your Bay Area routine of working out, playing piano, and slogging through college assignments. You were living with your mother, standing beside the loquat tree in your front yard, holding a letter with a Finnish return address. Mexican parrots shrieked from a neighbor’s dogwood tree. It was a warm May. You walked under the porch light and opened the envelope.

Dear Jeff,

So much has happened since I met you. I took your recommendation and read A Confederacy of Dunces. I laughed my ass off, but the book was so sad. I keep the book on my shelf and always think of you when I see it. You won’t believe this. I’m getting married! I have you to thank for this. I never thought I was the marrying type, but those two days I spent with you in Russia changed me. When I got back to Finland, I was restless, I thought about you constantly, and even at one time I had this mad idea that I should arrange to visit you, but a high school friend Oliver came into my life, and we began seeing each other, not as friends but as lovers. I have you to thank for this. Meeting you awakened a part of my soul that I had never known before. I hope that you don’t forsake love, as I had planned to do, that you too will find someone special in your life. You deserve it. You are an amazing man!

Love Always,

Tula

You stood there, staring at the letter, listening to the parrots cackling in the distance.

So that was your role—you were the guy who helped a sweet-souled depressive fall in love. Not with you. You weren’t the recipient of her love. You were the lighter fluid, the spark, the kindling that got her fire started. You’d made a difference.

You went inside, sat at your ebony Yamaha upright, and played something sad. You tried to imagine Tula as your audience, but her image was pushed out by the Russian Commander. You could see him sneering.

“You are a charlatan,” he said in your mind. “An American charlatan in Russia. You must always be put in your place. You must drink warm beer until you puke your guts out. Only then can you redeem your vain self.”

Over the years, the Commander had become a constant voice in your head—a reminder that you were pretentious, fraudulent, self-regarding. And maybe that wasn’t a bad thing. Maybe you needed him. He was the unexpected gift of a trip designed to make you a Communist but instead taught you to keep your inner ham in check.

Because an American charlatan in Russia was still a charlatan everywhere else.