I teach the student athletes at my college, and right now we’re exploring a question that cuts to the bone of modern life: Why are we so morally apathetic toward companies that feed our addictions, glamorize eating disorders, and employ CEOs who behave like cult leaders or predators?

We’ve watched three documentaries to anchor our research: Brandy Hellville and the Cult of Fast Fashion (Max), Trainwreck: The Cult of American Apparel (Max), and White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch (Netflix). Each one dissects a different brand, but the pathology beneath them is the same—companies built not on fabric, but fantasy. For four weeks, I lectured about this moral rot. My students listened politely. Eyes glazed. Interest flatlined. It was clear: they didn’t care about fashion.

So today, I tried something different. I told them to forget about the clothes. The essay, I explained, isn’t really about fashion—it’s about selling illusion. These brands were never peddling T-shirts or jeans; they were peddling a fantasy of beauty, popularity, and belonging. And they did it through something I called fake engagement—a kind of fever swamp where people mistake addiction for connection, and attention for meaning.

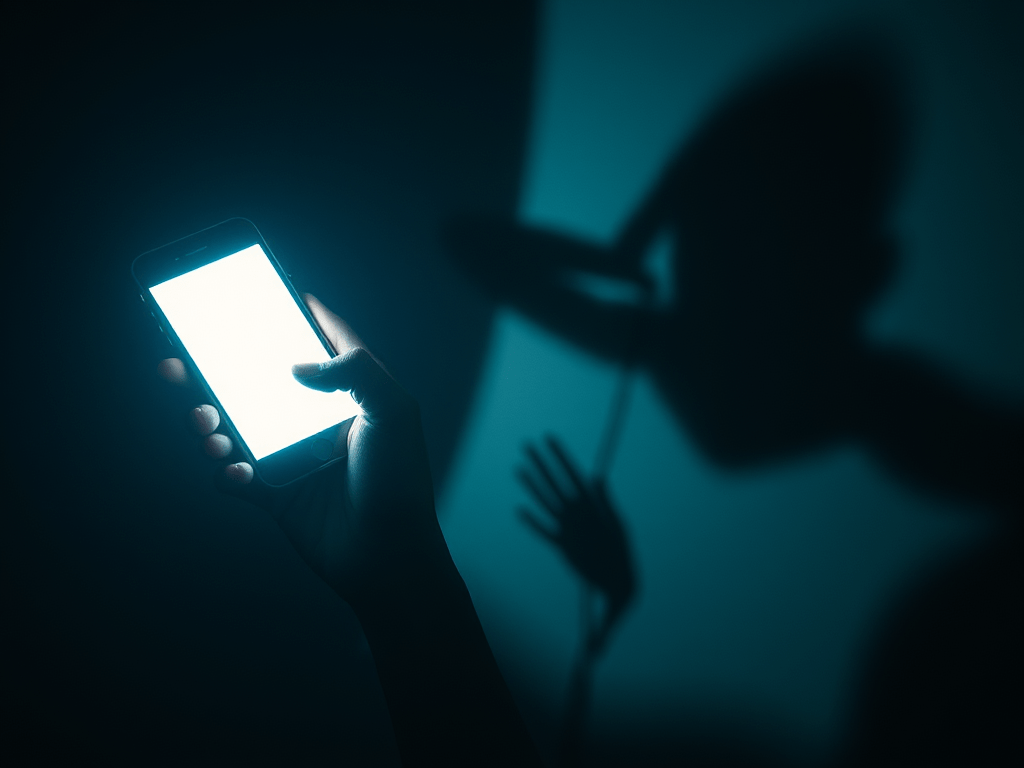

Fake engagement is the psychological engine of our times. It’s the dopamine loop of social media and the endless scroll. People feed their insecurities into it and get rewarded with the mirage of significance: likes, follows, attention. It’s an addictive system built on FOMO and self-erasure. Fake engagement is a demon. The more you feed it, the hungrier it gets. You buy things, post things, watch things, all to feel visible—and yet every click deepens the void.

This pathology is not confined to consumer brands. The entire economy now depends on it. Influencers sell fake authenticity. YouTubers stage “relatable” chaos. Politicians farm outrage to harvest donations. Every sphere of life—from entertainment to governance—has been infected by the logic of the algorithm: engagement above truth, virality above virtue.

I told my students they weren’t hearing anything new. The technologist Jaron Lanier has been warning us for over a decade that digital platforms are rewiring our brains, turning us into unpaid content providers for an economy of distraction. But then I reminded them that as athletes, they actually hold a kind of immunity to this epidemic.

Athletes can’t survive on fake engagement. They can’t pretend to win a game. They can’t filter a sprint or Photoshop a jump shot. Their work depends on real engagement—trust, discipline, and honest feedback. Their coaches demand evidence, not illusion. That’s what separates a competitor from a content creator. One lives in the real world; the other edits it out.

In sports, there’s no algorithm to flatter you. Reality is merciless and fair. You either make the shot or you don’t. You either train or you coast. You either improve or you plateau. The scoreboard has no patience for your self-image.

I contrasted this grounded reality with the digital circus we’ve come to call culture. Mukbang YouTubers stuff themselves with 10,000 calories on camera for likes. Watch obsessives blow through their savings chasing luxury dopamine. Influencers curate their “personal brand” as if selfhood were a marketing campaign. They call this engagement. I call it pathology. They’re chasing the same empty high that the fast-fashion industry monetized years ago: the belief that buying something—or becoming something online—can fill the hole of disconnection.

This is the epistemic crisis of our time: a collective break from reality. People no longer ask whether something is true or good; they ask whether it’s viral. We’re a civilization medicated by attention, high on engagement, and bankrupt in meaning.

That’s why I tell my athletes their essay isn’t about fashion—it’s about truth. About how human beings become spiritually and mentally sick when they lose their relationship to reality. You can’t heal what you refuse to see. And you can’t see anything clearly when your mind is hijacked by dopamine economics.

The world doesn’t need more influencers. It needs coaches—people who ground others in trust, expertise, and evidence. Coaches model a form of mentorship that Silicon Valley can’t replicate. They give feedback that isn’t gamified. They remind players that mastery requires patience, and that progress is measured in skill, not clicks.

When you think about it, the word coach itself has moral weight. It implies guidance, not manipulation. Accountability, not performance. A coach is the opposite of an influencer: they aren’t trying to be adored; they’re trying to make you better. They aren’t feeding your addiction to attention; they’re training your focus on reality.

I told my students that if society is going to survive this digital delirium, we’ll need millions of new coaches—mentors, teachers, parents, and friends who can anchor us in truth when everything around us is optimized for illusion. The fast-fashion brands we study are just one symptom of a larger disease: the worship of surface.

But reality, like sport, eventually wins. The body knows when it’s neglected. The mind knows when it’s being used. Truth has a way of breaking through even the loudest feed.

The good news is that after four weeks of blank stares, something finally broke through. When I reframed the essay—not as a takedown of fashion, but as a diagnosis of fake engagement—the room changed. My athletes sat up straighter. They started nodding. Their eyes lit up. For the first time all semester, they were engaged.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. The essay about fake engagement had just produced the real kind.