(or, The Fool’s Gamble Against Father Time)

There’s a special kind of delusion that whispers in our ears: You’re different. You’re special. The rules don’t apply to you. Other people? Sure, they age, they lose opportunities, they watch time slip through their fingers. But you—you will defy time. You will live in a perpetual Now, a beautiful, untouchable bubble where youth, dreams, and endless possibility never fade.

Phil Stutz has a name for the figure who shatters this illusion: Father Time—that grizzled old man with the hourglass, reminding us that our only real power lies in discipline, structure, and engagement with reality. Ignore him at your peril, because his wrath is merciless. Just ask Dexter Green, the tragic dreamer of Winter Dreams, who spends his life avoiding reality, chasing pleasure, and worshiping an illusion named Judy Jones.

Dexter believes he can live outside the real world, feeding off the fantasy of Judy rather than engaging with anything substantial. And for a while, this works. But Father Time is patient, and when Dexter finally wakes up, it’s too late.

Time Will Have Its Revenge

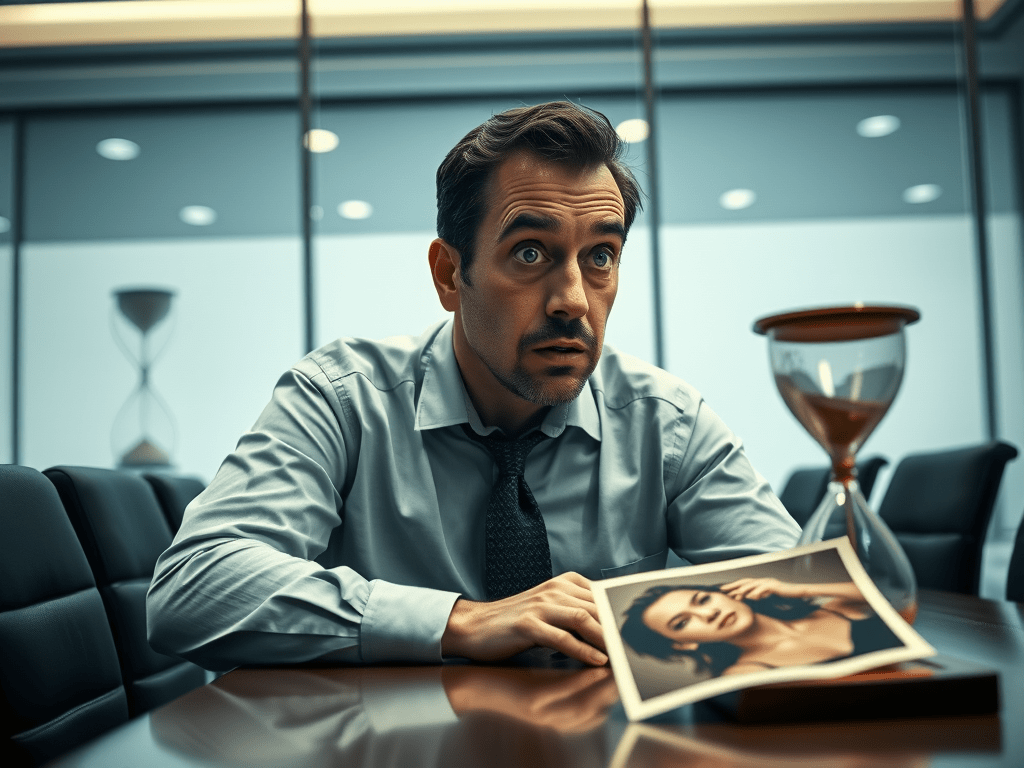

At thirty-two, long past his days of chasing the unattainable Judy, Dexter sits in a business meeting with a man named Devlin—a conversation that will destroy his last illusions.

Devlin delivers the blow: Judy is married now. Her name is Judy Simms, and her once dazzling, untouchable existence has collapsed into something horrifyingly mundane. Her husband is a drunk, an abuser, a tyrant. She is trapped in a miserable marriage to a man who beats her, then gets forgiven every time.

The once invincible, radiant Judy Jones, breaker of hearts, goddess of his dreams, is now an exhausted, aging housewife living under the rule of a man who treats her like dirt.

And just like that, Dexter’s winter dream crumbles into dust.

The Ultimate Betrayal: Time Wins, Beauty Fades, Illusions Die

The final insult comes when Devlin, with casual indifference, describes Judy as not all that special anymore—her once-mesmerizing beauty faded, her magic gone.

“She was a pretty girl when she first came to Detroit,” he says, as if commenting on an old piece of furniture.

For Dexter, this is not just a shock—it is the ultimate existential gut-punch.

For two decades, he has nourished his soul on the fantasy of Judy Jones, believing that she was something otherworldly, untouchable, worth sacrificing real life for. Now, in a single afternoon, he learns she was never a goddess, never unique, never even particularly remarkable.

Imagine having a high school crush, the Homecoming Queen, frozen in your memory as perfection itself. Then one day, you look her up on Facebook and she looks like Meat Loaf. That’s Dexter’s moment of reckoning.

His fantasy was never real. His youth is gone. His life has been wasted chasing an illusion. And now, standing in the wreckage, he feels the full force of Father Time’s judgment.

The “Butt on a Stick” Moment

In America, we have a phrase for the soul-crushing moment when reality smacks you so hard you can’t even breathe:

“Your butt has been handed to you on a stick.”

Dexter’s life has collapsed in on itself, and his first instinct is the same as anyone caught in the throes of devastation: This shouldn’t be happening to me.

But as Phil Stutz warns, that thought is pure insanity.

It is happening. It already happened. The more you protest, the more stuck you become. Stutz calls this victim mentality, the psychological quicksand that keeps people from ever moving forward. Dexter has two choices:

- Wallow in his misery, trapped in the wreckage of his illusions.

- Learn from his suffering and use it as a tool for transformation.

Breaking Free from the Winter Dream

And here’s where things get interesting: now that Dexter’s fantasy has been obliterated, he is free.

Yes, the truth is bitter. Yes, he wasted years chasing a ghost. But he is no longer chained to the illusion. The question now is: What does he do with that freedom?

Does he just find another “winter dream” to chase, another illusion to waste his life on? Or does he finally grow up and engage with reality?

What Would Phil Stutz Tell Dexter?

Stutz, co-author of The Tools, has a philosophy: Pain is a tool, not a punishment.

Most people, like Dexter, already know their problems. They just don’t know how to stop repeating them.

- Dexter knows he was obsessed with Judy Jones.

- Watch collectors know they keep rebuying the same watches they swore they’d never buy again.

- Food addicts know they shouldn’t be devouring that entire pizza at 11 p.m.

But knowing isn’t enough. You need tools to fight your worst instincts.

The Tools: How to Stop Wasting Your Life

Stutz realized that traditional therapy was useless—all it did was force people to dig deeper into their childhood wounds without ever giving them real solutions.

So he created The Tools—specific actions that force people to break free from their psychological traps.

Stutz doesn’t waste time on introspection without action. He knows that change happens when you move, engage, and disrupt your patterns.

- Stop trying to “think” your way out of your misery. Take action.

- Stop believing your problems are unique. They aren’t.

- Stop assuming time will wait for you. It won’t.

Part X: The Enemy Inside Your Head

The biggest enemy to change is what Stutz calls Part X—the part of you that wants to stay stuck, wants to keep wallowing in old habits, wants to keep clinging to comforting fantasies instead of engaging with reality.

And if you don’t fight Part X, you’ll waste your life exactly like Dexter did.

Final Lesson: Get Out of the Maze

If Dexter keeps fixating on his past, he will stay lost in the Maze—that endless loop of regret, nostalgia, and what-ifs that locks people in place while the world moves on without them.

If he accepts reality, uses his pain as a tool, and engages with life, then he has a chance at something real.

Because here’s the truth:

Father Time will take everything from you—except the lessons you learn and the actions you take.

Use them, or lose everything.