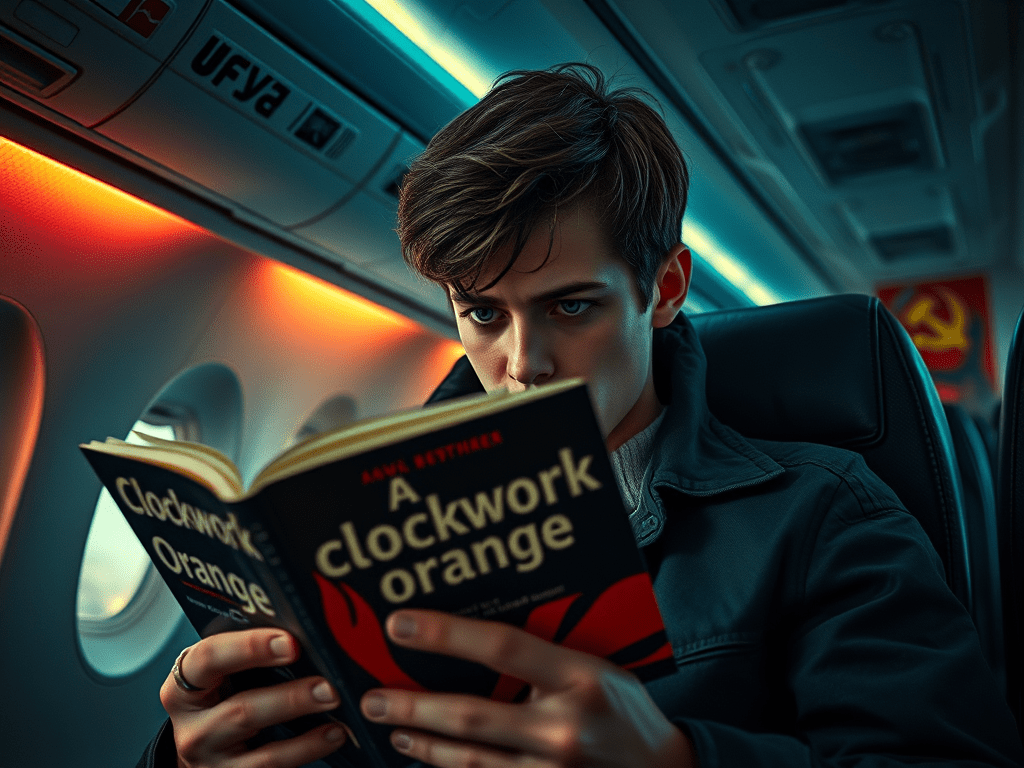

In my early twenties, I was holding a copy of A Clockwork Orange on an Aeroflot flight from New York to Moscow, and I was fairly certain I’d be arrested before I even touched Soviet soil. This was not the book I was supposed to be reading. My grandfather, a proud, card-carrying Communist, had made it clear that my in-flight reading should be Cities Without Crisis: The Soviet Union Through the Eyes of an American by Mike Davidow—a glowing, uncritical love letter to the USSR. According to Davidow, the Soviet Union was well on its way to utopia, a land where happy, apple-cheeked children played in clean, orderly cities, miraculously untouched by the crime, chaos, and moral decay of capitalist America.

I had every intention of honoring my grandfather’s wishes. He had, after all, funded my spot on this Sputnik Peace Tour, a Cold War-era cultural exchange designed to showcase the Soviet Union’s superiority and convince impressionable American university students that their homeland was little more than a dilapidated shack compared to the Soviet skyscraper. My grandfather, who spent his golden years vacationing in Russia and Cuba and had personally befriended Fidel Castro, hoped I’d return to the States ready to sing the Soviet anthem on command, with a crimson hammer-and-sickle tattoo stretched across my chest.

But try as I might, I couldn’t stomach Davidow’s propaganda. It read like an overlong infomercial scripted by a particularly humorless bureaucrat. Every page was predictable, every assertion dripping with a blind, almost devotional reverence for the Soviet system. By chapter three, my eyelids were growing heavier than a Soviet cement block. That’s when I ditched it for A Clockwork Orange, a novel that, in its satirical depiction of authoritarianism and mindless conformity, was just about the worst reading material one could bring on a goodwill trip to the USSR. My grandfather would have called it “reactionary,” but I wasn’t worried about him.

No, my real concern was the Soviet customs officers waiting for us on the tarmac. They’d be rummaging through our luggage, sniffing out any hint of anti-Soviet subversion. And there I was, gripping a book that, if noticed, might earn me an all-expenses-paid trip to the kind of re-education program I had no interest in attending.

When one of my fellow tourists, Jerry Gold, who was studying law at Brown University, saw me reading the subversive novel while sitting next to me on the plane, he warned me that the Soviet police would probably confiscate it when we got to the airport. “Not only will they take your book,” he said, “they will mark you as a troublemaker and keep tags on you throughout the entire trip. You must now constantly look over your shoulder for spies, my friend. And remember, if anyone wants to offer you good money for your jeans, it’s probably KGB. Selling Western commodities for the black market is a crime that could get you sent to a Soviet prison.”

I’ll admit, I was a little anxious about some stern-faced Soviet officer confiscating A Clockwork Orange from my hands, but that concern quickly took a backseat to a far more immediate crisis: the inedible horrors being passed off as food on the Aeroflot flight. The demure flight attendants, clad in their stiff, no-nonsense uniforms, moved through the cabin with a grim efficiency, depositing onto our trays what could only be described as Cold War rations—waxy cheese triangles entombed in foil, anemic cold cuts that looked like they had lost a war of their own, limp lettuce gasping for dignity, and carrot slices so soggy they seemed to be pre-chewed. It was a meal that could single-handedly refute Mike Davidow’s utopian vision in Cities Without Crisis. His thesis—that the Soviet Union was building thriving cities free of strife—collapsed under the weight of this culinary travesty. Because if a nation’s food is a reflection of its prosperity, then a country that serves despair on a tray is, in fact, in crisis. And a man who fails to acknowledge that crisis is a fraud.

Across the aisle, Jerry Gold, the kind of guy who exuded the unshakable self-assurance of someone who spent his summers at debate camp and his winters skiing in Vermont, curled his lip in disgust. A mop of reddish-brown hair and a constellation of freckles gave him the air of a scholarly leprechaun. He peeled back the foil on his cheese triangle with surgical precision, examined its plasticky surface like a jeweler appraising a fake diamond, and let out a slow, deliberate sigh. Then, in a display of Ivy League pragmatism, he took the industrial-grade brown napkin from his tray, folded it with the care of a man preparing for a high-stakes origami competition, and tucked it into the inner pocket of his coat. “You might want to do the same,” he advised me in a tone that suggested this was less a suggestion and more a survival strategy. I nodded, following suit, because when faced with Soviet airline cuisine, you learned to take advice from the man with a backup plan.

“This could be the only toilet paper you’re going to have on this trip,” he said. “You would be wise to save all your napkins. They’re worth their weight in gold around here.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“Have you ever used an Eastern European toilet?”

I shook my head.

“A hole in the ground. An invitation to the deep knee bend. It’s a free Jack Lalanne workout every time you go to the shitter. Things can be rather primitive.”

“For someone so hellbent on horrifying me on every aspect of this tour, can you please tell me why you decided to go on this trip?”

“It’s college credit. It’s exotic. How many Americans can boast of having been inside the Soviet Union?” He forced down a bite of cheese and asked me why I was going on the tour.

“My grandfather is a card-carrying communist,” I said. “He’s trying to convert me.”

“So he sent you to paradise.” He laughed, then pinched a cold cut, lifted it before his face, and scrutinized it carefully.

“The food isn’t a winning argument,” I said. “Nor is the absence of toilet paper.”

“There is a saying in the Soviet Union,” he said while tossing the uneaten cold cut on his tray. “If you see people standing in line, make sure you stand in it. People are always waiting in line for something.”

His statement proved to be true. A week later when we were in a sweltering market in Kyiv, we saw forlorn citizens, mostly stoic-faced babushkas, standing in a long line to buy wrinkled room-temperature chickens with flies swarming over them. I kept thinking to myself, “Cities without crisis? Bullshit.” Little did I know, I was standing 62 miles from Chernobyl and that two years later the nuclear reactor would explode causing worldwide radioactive contamination. Cities without crisis indeed.

But in 1984 as I witnessed long lines, food shortages, nonexistent toilet paper, and primitive toilets, I found something about the Soviet Union that struck me as almost admirable: Everywhere we went, markets, train stations, parks, and museums, there were government speakers playing classical music, much of it from Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, and Prokofiev. I wanted to believe, as my grandfather would want me to, that the violin chamber pieces and piano sonatas were the Soviet Union’s idea of music for the masses based on the government cultivating sophisticated taste in its citizens. But a darker motive was that the music was part of the Soviet Union’s propaganda: Classical music from Russian composers was a way of rebuking the vulgarity and corruption of the West.

Leave a comment