There are many ways to expose your raw, unfiltered self to the world. Some people achieve this through a near-death experience, a public meltdown, or a bout of food poisoning on an international flight. For me, claustrophobia is the great revealer, an unrelenting force that strips away every ounce of composure and leaves me flailing like a man trapped in quicksand. It doesn’t matter if I’m in a dentist’s chair or strapped into a sadistic amusement park ride—when the walls start closing in, I become the star of my own public humiliation showcase.

The first great revelation of my soul came at Universal Studios, where I made the tragic miscalculation of sacrificing my personal comfort for my wife and twin daughters. A father’s love is boundless, but so, unfortunately, was my terror. The very air of the place reeked of Las Vegas grift, stale churros, and desperate cash grabs. Every corner had some overenthusiastic performer in mothball-scented epaulets or a handlebar-mustached imposter butchering a French accent for a paycheck. But nothing could have prepared me for the medieval horror that awaited on the Harry Potter Forbidden Journey ride.

After standing in line for an eternity, I found myself wedged into an airplane seat designed for a malnourished Victorian child. A heavy metal harness slammed down on my 52-inch chest like a bear trap, and within seconds, my body entered full-blown rebellion mode. My lungs went on strike, my heart pounded out an emergency evacuation order, and my brain whispered, You are about to die in the most embarrassing way possible. As the conveyor belt dragged me toward a dark, swirling vortex of Hogwarts-themed doom, I did what any reasonable person would do—I began screaming like a man being lowered into a pit of snakes.

“STOP THE RIDE! I’M HAVING A HEART ATTACK!” I wailed, flailing like an air dancer outside a used car lot.

At first, no one in charge seemed to care, but the fellow prisoners trapped beside me picked up on my panic and began chanting my cause like a medieval mob: “STOP THE RIDE! STOP THE RIDE!” Finally, a burly security officer in an FBI-grade sport coat emerged, walkie-talkie in hand, and surveyed my meltdown with the practiced patience of a man who had seen worse. I looked up at him, sheepish and sweaty, and asked, “Do you need to take me to a debriefing room?” He chuckled, helped me out of my restraints, and sent me shuffling out of Universal Studios, a broken man.

But the universe was not done exposing my fragility.

The Dentist’s Chair: A Torture Chamber Disguised as Healthcare

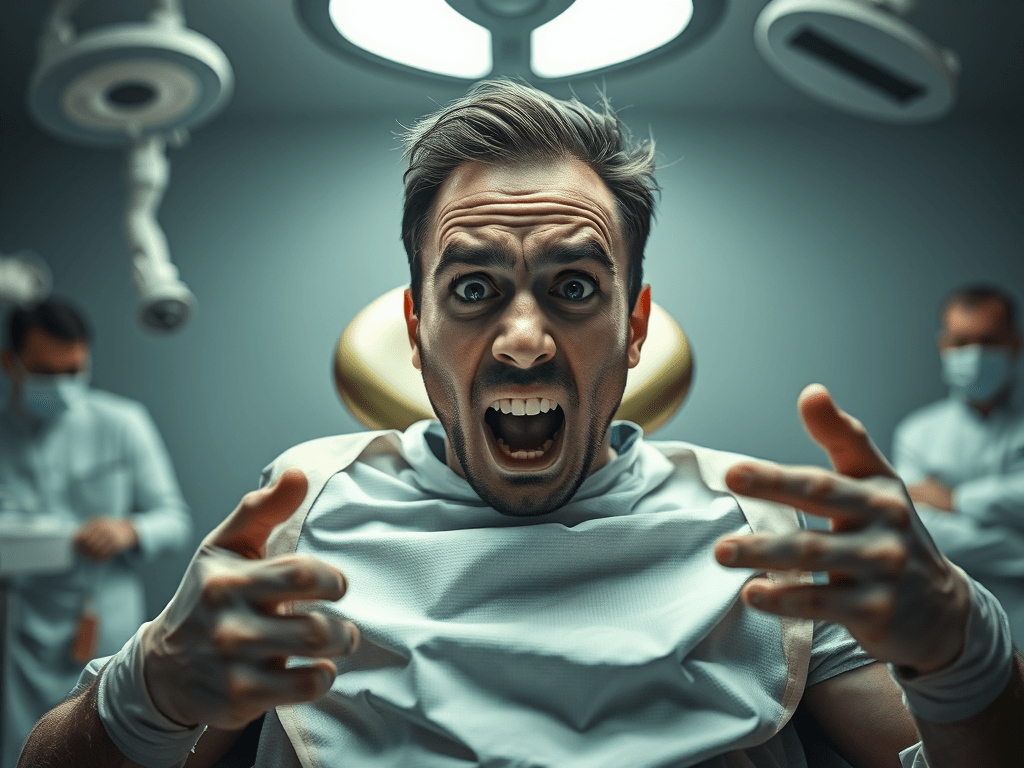

Around the same time as the Universal Studios fiasco, I had a similarly catastrophic loss of dignity at Dr. Howard Chen’s dental office. The appointment started out fine—numbing shots, ear-splitting drills, the usual dance with mortality. But then the bite block came out. For those blissfully unaware, a bite block is a rubber wedge designed to keep your mouth open during dental procedures, but in my case, it may as well have been a medieval jaw clamp designed by Torquemada himself.

The second it locked my mouth open, my brain fired off the same claustrophobic distress signal as it had on the Harry Potter ride. I couldn’t swallow, which meant I couldn’t breathe, which meant I was about to die, right there, in a flannel shirt, under a fluorescent light, to the soft rock stylings of The Carpenters.

Before I could stop myself, I ripped off my shirt, launched myself out of the dental chair, and began gasping like a shipwreck survivor.

“Are you going to be okay, Jeff?” Dr. Chen asked, his voice dripping with the calm patience of a man who has dealt with neurotics before.

“I CAN’T HAVE THIS RUBBER THING IN MY MOUTH,” I announced, holding the bite block aloft like a relic from an exorcism.

Dr. Chen nodded, his eyes a mix of concern and professional detachment. “Okay, we’ll do it without the bite block.” He gestured toward the chair. “Go ahead and sit back down.”

I obeyed, heart pounding, and the rest of the drilling continued without further catastrophe. But the damage to my dignity was irreversible.

Sensory Hell: The Dentist’s Office Smells Like Death

The claustrophobia is bad enough, but what really pushes me over the edge is that I am what some might call a “super smeller.” Lying in the dental chair, I am forced to marinate in an unholy stew of:

- Clove oil

- Formaldehyde

- Acrylic

- Glutaraldehyde

- Latex gloves

- The lingering decay of other patients’ tooth dust

It is the aroma of death itself. I am not a dental patient—I am a cadaver in the early stages of embalming.

And while I fight off nausea, my mind spirals into a full existential crisis. Something about lying prone, mouth pried open, surgical tools scraping at my enamel, makes me contemplate my soul more than any other moment in my life. The sheer vulnerability of the position mimics some prelude to the afterlife, and I am left with only my own morbid thoughts for company.

Morbidity Hits Different with 1970s Soft Rock

As if my anxiety needed any further provocation, Dr. Chen’s office plays 1970s easy listening on a continuous loop. The Carpenters, Neil Diamond, John Denver—songs that transport me straight back to my early years as a melancholic prepubescent. Suddenly, I am ten years old again, scribbling dramatic diary entries about my unrequited love for Patty Wilson, the rosy-cheeked blonde girl from fourth grade who never knew I existed.

But before I can fully dissolve into a puddle of nostalgic despair, Dr. Chen interrupts.

“You’re brushing too hard,” he warns. “You’re murdering your gum line.”

“But I don’t trust the Sonicare to do the job!” I protest.

“You need to have faith in the Sonicare, Jeff.”

“But I am a man of doubt.”

Dr. Chen sighs, shaking his head. “I can see that.”

Final Humiliation: The Dentist Knows I’m Crazy

During my latest visit, he threw a new horror into the mix: the possibility of a root canal.

“What can I do to avoid it?” I asked, racked with dread.

“Relax, Jeff,” he said. “All this stress is hurting your immune system. You need a strong immune system to fight decay.”

Great. Now I have to worry about stress-induced tooth rot.

As I staggered out of the office, I nearly reversed into an angry SUV driver, who honked with the force of a nuclear siren. But what truly shattered me was the sight of Dr. Chen, peering through his office window, watching the entire debacle unfold.

And in that moment, as our eyes met, I knew—I was, without a doubt, the most unhinged patient he had ever seen. There would be no coming back from this.

Claustrophobia, once again, had revealed my true soul to the world.

Leave a comment