Yesterday, the tour bus wheezed to a stop and dumped us in Little Havana like a sack of reluctant tourists. We wandered through downtown under a punishing sun, the air thick with the scent of café Cubano and bravado. That’s when I saw him: a man who looked exactly like Lalo Salamanca, minus the drug empire—crisp white shirt, swagger in his step, and two kids in tow. He wasn’t just crossing the street; he was gliding, chin up, radiating unfiltered, unstudied masculinity. And he wasn’t alone. Little Havana was teeming with these men—fathers who looked like they’d stepped out of a sepia-toned photo labeled Pride, circa Always.

Meanwhile, there’s me—63 years old, 30 pounds overweight despite daily exercise and good intentions. My daughters joke that I look like Charlie Brown, and not in the charming, animated special way—more in the “existential dread in khakis” sense. I don’t walk across intersections like Lalo. I trudge. And if I’m holding hands, it’s probably because I’m being led away from a pastry counter.

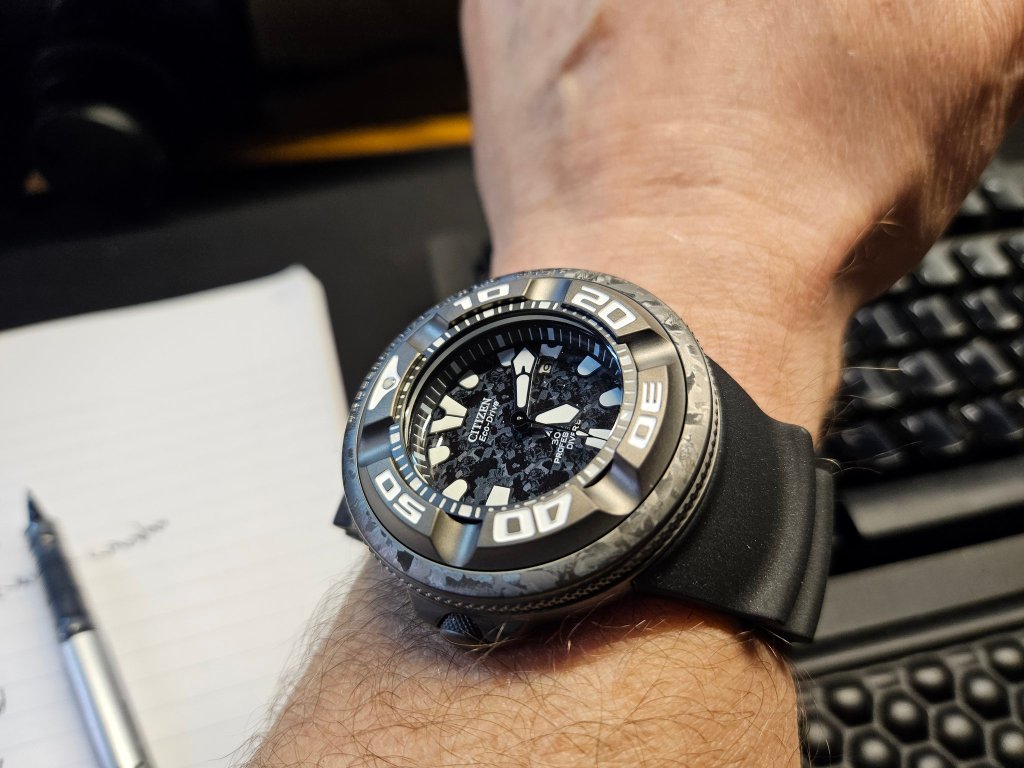

But as I watched those fathers—their confidence, their presence—I began to realize the true pathology behind my watch obsession. I wasn’t just collecting watches. I was searching for transformation. If I could find the watch, the perfect timepiece, it might just alchemize my Charlie Brown soul into something closer to Lalo—proud, magnetic, quietly heroic.

Enter the Seiko Astron Nexter—$1,700 of satellite-synced wizardry and horological lust. It gleams. It commands respect. It’s whispering, “Buy me, and become the man you were meant to be.” But let’s be real: I barely go anywhere these days. My public appearances are limited to grocery store aisles and accidental mirror encounters. I’m not a man about town; I’m a man about tuna salad and ibuprofen.

At 63, how many years of wrist real estate do I even have left? How long before I’m just another well-accessorized ghost, my legacy a drawer of luxury regret? The whole ritual—buying, flipping, rationalizing, repenting—is starting to feel less like a hobby and more like a slow, polished breakdown. This isn’t taste. It’s compulsion with a tracking number.

Maybe it’s time to quit. I’ve got five watches already—each one a chapter in the memoir of my delusions. Maybe the next chapter isn’t about adding to the collection, but about burning the altar down.

Here’s a wild idea: make self-denial the new dopamine hit. Let the new obsession be calorie restriction instead of case diameter. Let others chase sapphire crystals and ceramic bezels—I’ll chase a slimmer waistline, a clean mind, and the kind of inner quiet no chronograph can measure.

Because maybe happiness isn’t behind a glass display case. Maybe it’s not ticking on my wrist. Maybe it’s the empty space where the craving used to be.

Still… the Astron is beautiful. And it would look damn good on Lalo.