In On Writing and Failure, Stephen Marche shows zero patience for the self-help fable that “failure leads to success.” The myth says: suffer now, triumph later; keep grinding and the universe will eventually reward you. Marche calls this narrative pure nonsense. His friendships with writers who have made millions and basked in praise only confirm the truth: acclaim doesn’t cure insecurity, fame doesn’t dissolve alienation, and even celebrated authors carry the bruises of obscurity under their tuxedos. They remain misunderstood, jealous, anxious, and haunted by irrelevance. Success doesn’t banish failure—it merely decorates it. Celebrity is not salvation; it is a spotlight that makes the neediness easier to see.

Marche believes the situation is worsening. We live, he argues, in a cultural moment where institutions are collapsing and traditional literary prestige has been replaced by digital noise. Novelists chase television deals. Journalists pivot into professional outrage machines. The literary public square has splintered into algorithmic micro-audiences. And in this fractured landscape, the writer’s deepest fear is not rejection—it’s evaporation. Not being debated, but forgotten.

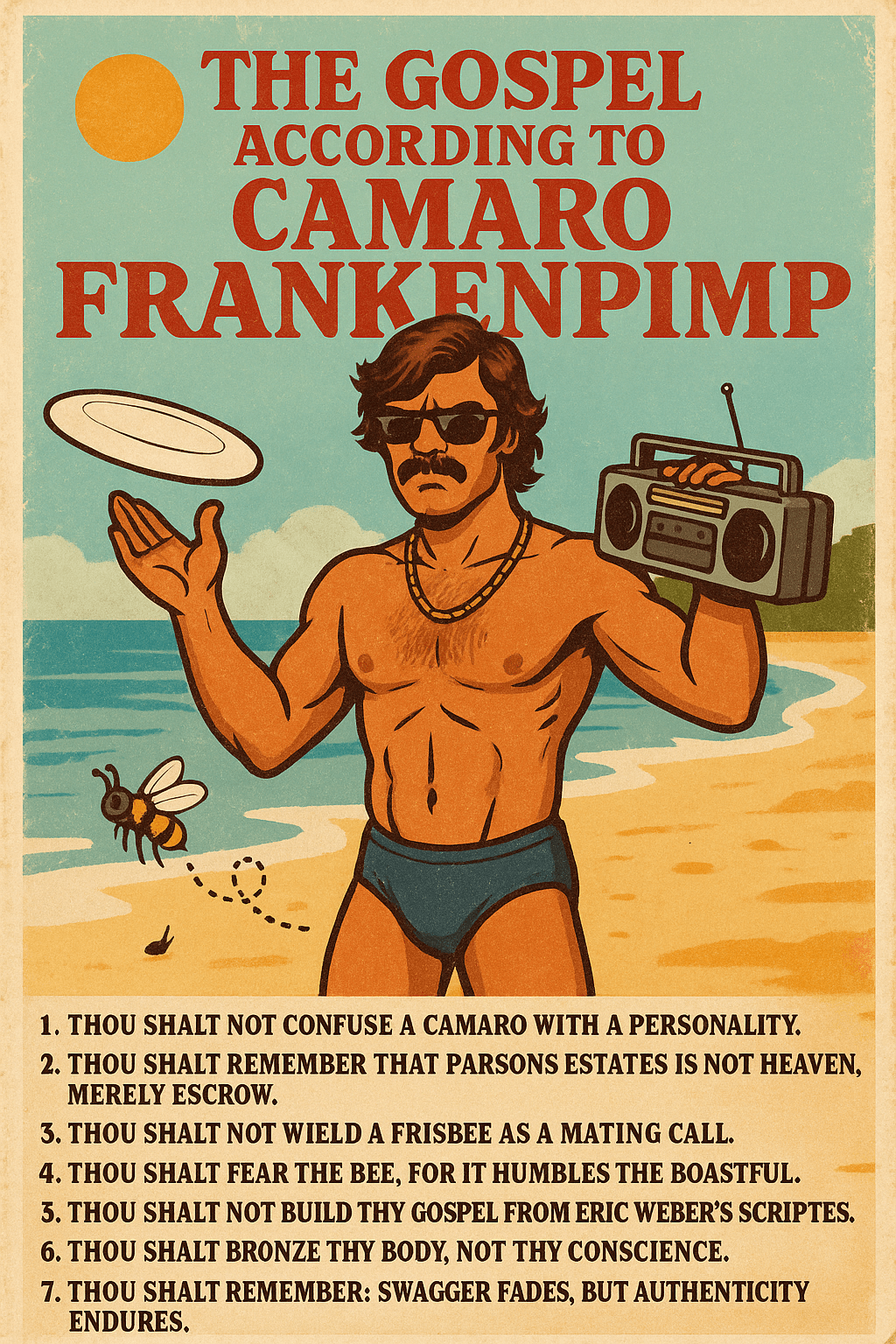

Even the “independent writer revolution” gets little mercy from Marche. Platforms come and go, each proclaimed the future of writing, each eventually forgotten. “Every few years there’s some new great hope—right now it’s Substack,” he writes. Then comes the hammer: “Substack will die or peter out just like the rest.” The point is not cynicism for sport; it is a reminder that technology cannot build the cathedral that literary culture once occupied. The medium keeps changing; the instability remains constant.

As a reader drowning in subscriptions, I find his skepticism refreshing. I can’t reasonably pay $60 to $120 a year for dozens of Substack writers I admire. If I did, I’d be shelling out ten grand annually just to keep up. That is not a sustainable model for anyone but tech-company accountants. So yes, blogs collapsed, digital magazines buckled, and Substack may be next. Writers are still wandering, looking for a home that isn’t a platform built on a countdown timer. We are living in a literary diaspora—talent everywhere, shelter nowhere.