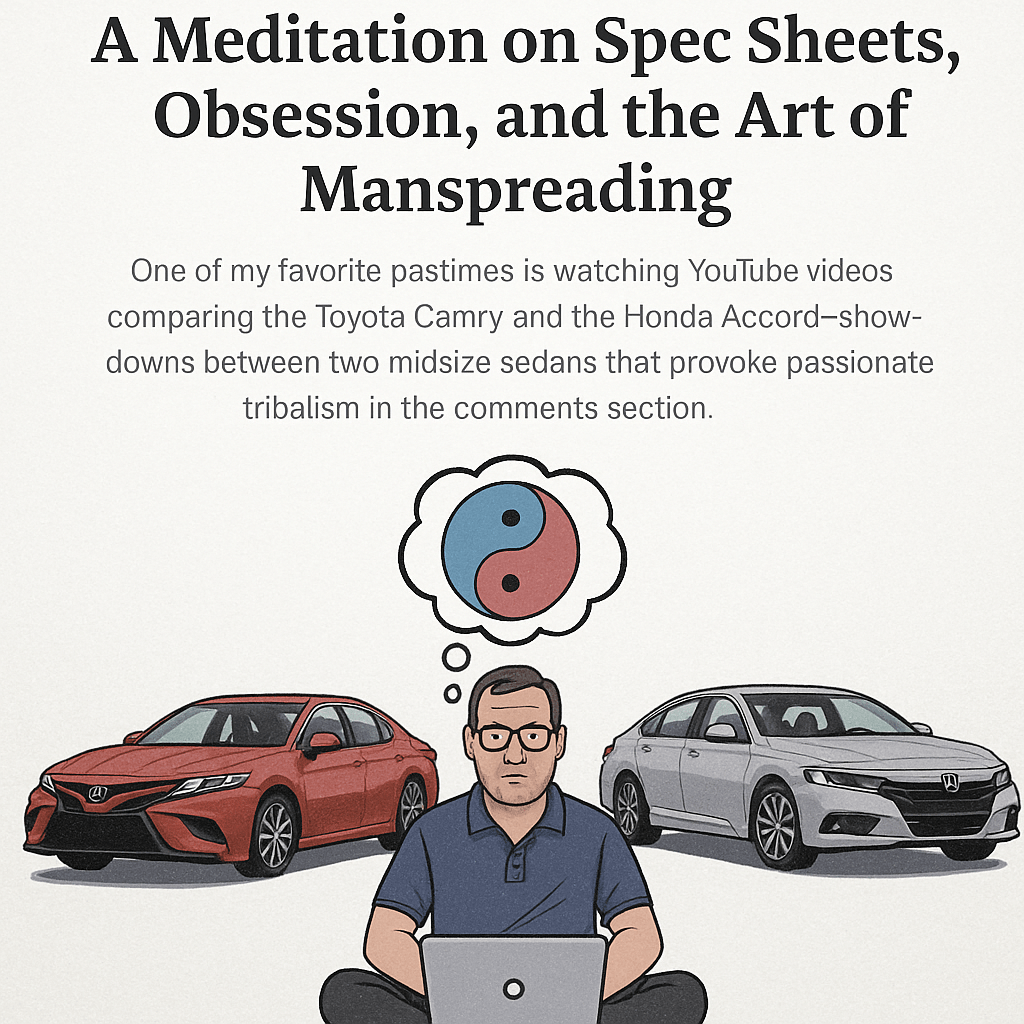

One of my favorite pastimes—oddly specific and strangely soothing—is watching YouTube comparison videos of the Toyota Camry vs. the Honda Accord. I’m not car shopping. I don’t need a car. I may never buy another car. But these videos are my digital comfort food. They’re as satisfying to me as fine wine is to a sommelier or apple pie tastings are to a pastry chef—only instead of tasting notes, I savor engine specs and torque curves.

There’s something singular about the Camry-Accord rivalry. In the sedan world, these two are the Goliaths. It’s not just another car comparison. It’s the comparison. Watching these two go head-to-head year after year is like seeing the best Steelers team take on the peak Patriots in a Super Bowl that never ends. Everything else—BMW vs. Mercedes, Rolex vs. Omega—feels less pure. BMW and Mercedes aren’t in the same pricing tier. Rolex exists in a brand vacuum. And while coffee maker comparisons have their niche charm, they lack the existential gravity of Camry vs. Accord.

No rivalry inspires more content—or more heated debate. YouTube is flooded with these matchups, and if you scan the view counts, it’s clear: Camry vs. Accord is the king of consumer showdowns. Reviewers comb over the details with forensic intensity—fuel economy, powertrain specs, road noise, trunk space, rear-seat legroom, infotainment ergonomics, ride comfort, styling. They break it down like seminary students parsing Greek New Testament syntax.

But what really fascinates me is the comments section, where strangers proclaim their loyalty with righteous conviction. Owners justify their purchase with religious fervor, deploying cherry-picked data to reinforce their superiority. It’s a textbook case of post-purchase rationalization: that psychological reflex where we inflate the virtues of what we bought to feel smarter, savvier, and self-assured.

One commenter might praise the Accord’s refined cabin and roomier interior—but add that its exterior is so bland, driving one is akin to living as an NPC. Another insists Camry’s superior sales figures are proof of its aesthetic and mechanical dominance. Some dismiss the Accord entirely, predicting its extinction in five years. Others proudly declare they’re on their fifth generation of the same car, with brand loyalty woven into the fabric of their identity. For these drivers, the car isn’t a tool—it’s family.

Ultimately, this rivalry isn’t really about cars. It’s about identity, tribalism, and the human need to choose a side and be right. It’s a Dr. Seussian fable in metallic paint: one team wears Honda badges, the other wears Toyota, and both believe their side represents reason, taste, and truth.

For those of us with no appetite for political tribalism, this is our outlet. Camry vs. Accord is safer ground—less polarizing than politics, but don’t tell that to a diehard on either side. Watch how they argue: calmly, firmly, methodically—as if their livelihood depends on selecting the superior midsize sedan. They approach the debate with the solemnity of theologians discussing substitutionary atonement or post-mortem salvation.

And me? I’m both relaxed and riveted. The debate calms my nerves and sharpens my focus. For a glorious hour, as I parse suspension tuning and rear-seat headroom, my worries dissolve. My thoughts narrow into something blissful. I study the specs like they’re verses from Leviticus. And in that deep focus, my anxiety lifts.

Then it hits me: I don’t actually want the car—I want the focus. The Camry and Accord are just proxies for obsession. They’re placeholders in the temple of hyper-attention. Some people do yoga. I watch two middle-aged men compare infotainment systems like Cold War arms inspectors.

And I do this with full self-awareness. I said earlier I might never buy another car. That wasn’t entirely true. My wife owns a 2014 silver Honda Accord Sport. I drive a 2018 gunmetal gray Accord Sport. We’re a two-Accord household. When it comes to car-buying, I’m conservative by nature—and what’s more conservative than buying a Camry or an Accord?

I’m nearly certain our next car—whether hers or mine—will be one of the two. Likely an Accord, given that I’m six feet tall, 230 pounds, claustrophobic, and deeply committed to driver’s seat manspreading. The Accord gives me room to sprawl. The Camry? Not so much. I know this because, during a San Francisco vacation, an Uber driver picked us up in a brand-new Camry. It looked sleek from the curb, but once inside I felt like I was strapped into a fetal position. The experience ruined the car for me.

And yet, I want to love the Camry. I really do. In my ideal life, my driveway would have both: the Camry and the Accord parked side by side like yin and yang. One the smooth operator, the other the sensible sibling. Their competition makes each better. Their rivalry sustains them both—and keeps me obsessively circling the rabbit hole.

Because in the end, the Camry vs. Accord battle isn’t just about choosing a car. It’s about longing for clarity in a world of noise. It’s about choosing sides, rationalizing decisions, and pretending—for a few hours on YouTube—that the world makes sense if you can just pick the right sedan.