Sample Thesis Statement:

In “Joan Is Awful,” the titular character stumbles into ruin not because she’s evil, but because she’s deluded—clinging to a flattering self-image while ignoring the yawning chasm between how she sees herself and how others do. Her desperate need for approval blinds her to the hollow spectacle of parasocial fame, where the Streamberry audience gorges on her curated misery with slack-jawed glee and not an ounce of empathy. Meanwhile, Joan’s passive embrace of digital convenience—those sleek platforms that promise connection, ease, and relevance—costs her everything: privacy, agency, even identity. As her most intimate moments are vacuumed into the cloud, diced into monetizable data, and reassembled into lurid entertainment, Joan learns the hard way that algorithms don’t care about narrative nuance—they just want content. In the end, she’s not the star of her own life. She’s tech industry chum, chewed up and streamed.

Outline (9 Paragraphs):

1. Introduction: The Mirror Cracks

Set the tone by describing Joan’s glossy, curated digital life as a carefully lit Instagram photo—harmless on the surface, but riddled with cracks. Preview the idea that “Joan Is Awful” isn’t just a satire about tech—it’s a psychological horror story about self-delusion, digital exploitation, and the death of narrative control.

2. The Selfie Delusion: Joan’s Inflated Self-Perception

Explore Joan’s internal image of herself as a reasonable, competent, kind professional. Contrast this with the version that appears on Streamberry: vain, passive-aggressive, and spineless. Argue that the episode’s central irony lies in Joan’s shock—not at being watched, but at being seen too clearly.

3. The Streamberry Effect: Fame Without Love

Analyze the parasocial dimension: Joan’s life is turned into a binge-worthy drama, but there’s no affection in the audience’s gaze. They’re not fans; they’re voyeurs. The more humiliating the content, the more addicted they become. This is the dopamine economy, and Joan is its punchline.

4. Compliance and Convenience: How She Handed Over the Keys

Joan doesn’t get hacked—she clicks “Accept Terms and Conditions.” Show how the episode weaponizes our own tech complacency. Her ruin begins with a shrug. She wanted frictionless tech. What she got was soul extraction via user agreement.

5. Raw Data, Real Damage: The Monetization of Intimacy

Dig into the idea that Joan’s emotions, her breakups, her therapist visits, even her sex life—all become commodities. They’re no longer private moments, but digital product. The episode skewers the idea that tech is neutral. It’s a vampire, and your heart is just another bite-sized upload.

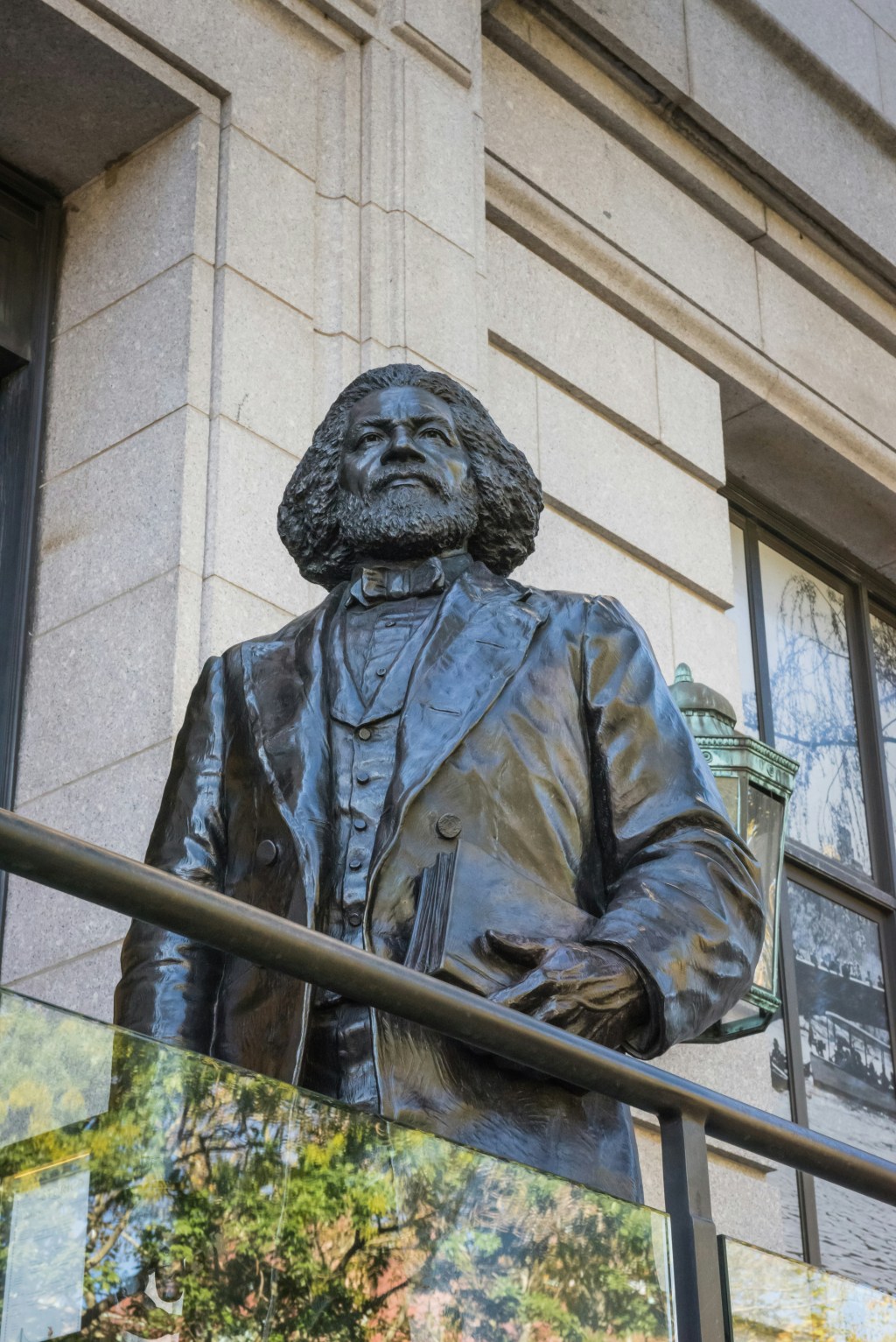

6. Algorithmic Authoritarianism: The Tyranny of Predictive Systems

Focus on the moment when Joan realizes she’s been living inside a nested simulation created by AI. Explain how this metaphor extends beyond science fiction—it mirrors the way our lives are shaped, nudged, and pre-written by recommendation engines, targeted ads, and invisible code.

7. Narrative Collapse: When You’re No Longer the Main Character

Explore the existential horror of losing narrative control. Joan’s identity dissolves not just because she’s surveilled, but because she can no longer steer the story. She’s overwritten by code, versioned into oblivion, rendered into a flattened character in someone else’s plot.

8. Final Descent: From Star to Spectacle to Scrub

Track Joan’s downward spiral as she tries to fight the system, only to discover that her rebellion has already been commodified. Even her attempts to resist are folded into more content. Her final fate isn’t tragic—it’s product placement.

9. Conclusion: A Warning Disguised as Entertainment

Tie everything back to the real world. We are all Joan to some degree—curating, consenting, surrendering. Streamberry may be fictional, but the forces it parodies are not. End with a sharp jab: the next time you agree to terms of service without reading, remember Joan. She clicked too.