My colleagues in the English Department were just as rattled as I was by the AI invasion creeping into student assignments. So, a meeting was called—one of those “brown bag” sessions, which, despite being optional, had the gravitational pull of a freeway pile-up. The crisis of the hour? AI.

Would these generative writing tools, adopted by the masses at breakneck speed, render us as obsolete as VHS repairmen? The room was packed with jittery, over-caffeinated professors, myself included, all bracing for the educational apocalypse. One by one, they hurled doomsday scenarios into the mix, each more dire than the last, until the collective existential dread became thick enough to spread on toast.

First up: What do you do when a foreign language student submits an essay written in their native tongue, then let’s play translator? Is it cheating? Does the term “English Department” even make sense anymore when our Los Angeles campus sounds like a United Nations general assembly? Are we teaching “English,” or are we, more accurately, teaching “the writing process” to people of many languages with AI now tagging along as a co-author?

Next came the AI Tsunami, a term we all seemed to embrace with a mix of dread and resignation. What do we do when we’ve reached the point that 90% of the essays we receive are peppered with AI speak so robotic it sounds like Siri decided to write a term paper? We were all skeptical about AI detectors—about as reliable as a fortune teller reading tea leaves. I shared my go-to strategy: Instead of accusing a student of cheating (because who has time for that drama?), I simply leave a comment, dripping with professional distaste: “Your essay reeks of AI-generated nonsense. I’m giving it a D because I cannot, in good conscience, grade this higher. If you’d like to rewrite it with actual human effort, be my guest.” The room nodded in approval.

But here’s the thing: The real existential crisis hit when we realized that the hardworking, honest students are busting their butts for B’s, while the tech-savvy slackers are gaming the system, walking away with A’s by running their bland prose through the AI carwash. The room buzzed with a strange mixture of outrage and surrender—because let’s be honest, at least the grammar and spelling errors are nearly extinct.

As I walked out of that meeting, I had a new writing prompt simmering in my head for my students: “Write an argumentative essay exploring how AI platforms like ChatGPT will reshape education. Project how these technologies might be used in the future and consider the ethical lines that AI use blurs. Should we embrace AI as a tool, or do we need hard rules to curb its misuse? Address academic integrity, critical thinking, and whether AI widens or narrows the education gap.”

When I got home that day, gripped by a rare and fleeting bout of efficiency, I crammed my car with a mountain of e-waste—prehistoric laptops, arthritic tablets, and cell phones so ancient they might as well have been carved from stone. Off to the City of Torrance E-Waste Drive I went, joining a procession of guilty consumers exorcising their technological demons, all of us making way for the next wave of AI-powered miracles. The line stretched endlessly, a funeral procession for our obsolescent gadgets, each of us unwitting foot soldiers in the ever-accelerating war of planned obsolescence.

As I inched forward, I tuned into a podcast—Mark Cuban sparring with Bill Maher. Cuban, ever the capitalist prophet, was adamant: AI would never be regulated. It was America’s golden goose, the secret weapon for maintaining global dominance. And here I was, stuck in a serpentine line of believers, each of us dumping yesterday’s tech sins into a giant industrial dumpster, fueling the next cycle of the great AI arms race.

I entertained the thought of tearing open my shirt to reveal a Captain America emblem, fully embracing the absurdity of it all. This wasn’t just teaching anymore—it was an uprising. If I was going to lead it, I’d need to be Moses descending from Mount Sinai, armed not with stone tablets but with AI Laws. Without them, I’d be no better than a fish flopping helplessly on the banks of a drying river. To enter this new era unprepared wasn’t just foolish—it was professional malpractice. My survival depended on understanding this beast before it devoured my profession.

That’s when the writing demon slithered in, ever the opportunist.

“These AI laws could be a book. Put you on the map, bro.”

I rolled my eyes. “A book? Please. Ten thousand words isn’t a book. It’s a pamphlet.”

“Loser,” the demon sneered.

But I was older now, wiser. I had followed this demon down enough literary dead ends to know better. The premise was too flimsy. I wasn’t here to write another book—I was here to write a warning against writing books, especially in the AI age, where the pitfalls were deeper, crueler, and exponentially dumber.

“I still won,” the demon cackled. “Because you’re writing a book about not writing a book. Which means… you’re writing a book.”

I smirked. “It’s not a book. It’s The Confessions of a Recovering Writing Addict. So pack your bags and get the hell out.”

***

My colleague on the technology and education committee asked me to give a presentation for FLEX day at the start of the Spring 2025 semester. Not because I was some revered elder statesman whose wisdom was indispensable in these chaotic times. No, the real reason was far less flattering: As an incurable Manuscriptus Rex, I had been flooding her inbox with my mini manifestos on teaching writing in the Age of AI, and saddling me with this Herculean task was her way of keeping me too busy to send any more. A strategic masterstroke, really.

Knowing my audience would be my colleagues—seasoned professors, not wide-eyed students—cranked the pressure to unbearable levels. Teaching students is one thing. Professors? A whole different beast. They know every rhetorical trick in the book, can sniff out schtick from across campus, and have a near-religious disdain for self-evident pontification. If I was going to stand in front of them and talk about teaching writing in the AI Age, I had better bring something substantial—something useful—because the one thing worse than a bad presentation is a room full of academics who know it’s bad and won’t bother hiding their contempt.

To make matters worse, this was FLEX day—the first day back from a long, blissful break. Professors don’t roll into FLEX day with enthusiasm. They arrive in one of two states: begrudging grumpiness or outright denial, as if by refusing to acknowledge the semester’s start, they could stave it off a little longer. The odds of winning over this audience were not just low; they were downright hostile.

I felt wildly out of my depth. Who was I to deliver some grand pronouncement on “essential laws” for teaching in the AI Age when I was barely keeping my own head above water? I wasn’t some oracle of pedagogical wisdom—I was a mole burrowing blindly through the shifting academic terrain, hoping to sniff my way out of catastrophe.

What saved me was my pride. I dove in, consumed every article, study, and think piece I could find, experimented with my own writing assignments, gathered feedback from students and colleagues, and rewrote my presentation so many times that it seeped into my subconscious. I’d wake up in the middle of the night, drool on my face, furious that I couldn’t remember the flawless elocution of my dream-state lecture.

Google Slides became my operating table, and I was the desperate surgeon, deleting and rearranging slides with the urgency of someone trying to perform a last-minute heart transplant. To make things worse, unlike a stand-up comedian, I had no smaller venue to test my material before stepping onto what, in my fevered mind, felt like my Netflix Special: Teaching Writing in the AI Age—The Essential Guide.

The stress was relentless. I woke up drenched in sweat, tormented by visions of failure—public humiliation so excruciating it belonged in a bad movie. But I kept going, revising, rewriting, refining.

***

During the winter break as I prepared my AI presentation, I recall one surreal nightmare—a bureaucratic limbo masquerading as a college elective. The course had no purpose other than to grant students enough credits to graduate. No curriculum, no topics, no teaching—just endless hours of supervised inertia. My role? Clock in, clock out, and do absolutely nothing.

The students were oddly cheerful, like campers at some low-budget retreat. They brought packed lunches, sprawled across desks, and killed time with card games and checkers. They socialized, laughed, and blissfully ignored the fact that this whole charade was a colossal waste of time. Meanwhile, I sat there, twitching with existential dread. The urge to teach something—anything—gnawed at my gut. But that was forbidden. I was there to babysit, not educate.

The shame hung on me like wet clothes. I felt obsolete, like a relic from the days when education had meaning. The minutes dragged by like a DMV line, each one stretching into a slow, agonizing eternity. I wondered if this Kafkaesque hell was a punishment for still believing that teaching is more than glorified daycare.

This dream echoes a fear many writing instructors share: irrelevance. Daniel Herman explores this anxiety in his essay, “The End of High-School English.” He laments how students have always found shortcuts to learning—CliffsNotes, YouTube summaries—but still had to confront the terror of a blank page. Now, with AI tools like ChatGPT, that gatekeeping moment is gone. Writing is no longer a “metric for intelligence” or a teachable skill, Herman claims.

I agree to an extent. Yes, AI can generate competent writing faster than a student pulling an all-nighter. But let’s not pretend this is new. Even in pre-ChatGPT days, students outsourced essays to parents, tutors, and paid services. We were always grappling with academic honesty. What’s different now is the scale of disruption.

Herman’s deeper question—just how necessary are writing instructors in the age of AI—is far more troubling. Can ChatGPT really replace us? Maybe it can teach grammar and structure well enough for mundane tasks. But writing instructors have a higher purpose: teaching students to recognize the difference between surface-level mediocrity and powerful, persuasive writing.

Herman himself admits that ChatGPT produces essays that are “adequate” but superficial. Sure, it can churn out syntactically flawless drivel, but syntax isn’t everything. Writing that leaves a lasting impression—“Higher Writing”—is built on sharp thought, strong argumentation, and a dynamic authorial voice. Think Baldwin, Didion, or Nabokov. That’s the standard. I’d argue it’s our job to steer students away from lifeless, task-oriented prose and toward writing that resonates.

Herman’s pessimism about students’ indifference to rhetorical nuance and literary flair is half-baked at best. Sure, dive too deep into the murky waters of Shakespearean arcana or Melville’s endless tangents, and you’ll bore them stiff—faster than an unpaid intern at a three-hour faculty meeting. But let’s get real. You didn’t go into teaching to serve as a human snooze button. You went into sales, whether you like it or not. And this brings us to the first principle of teaching in the AI Age: The Sales Principle. And what are you selling? Persona, ideas, and the antidote to chaos.

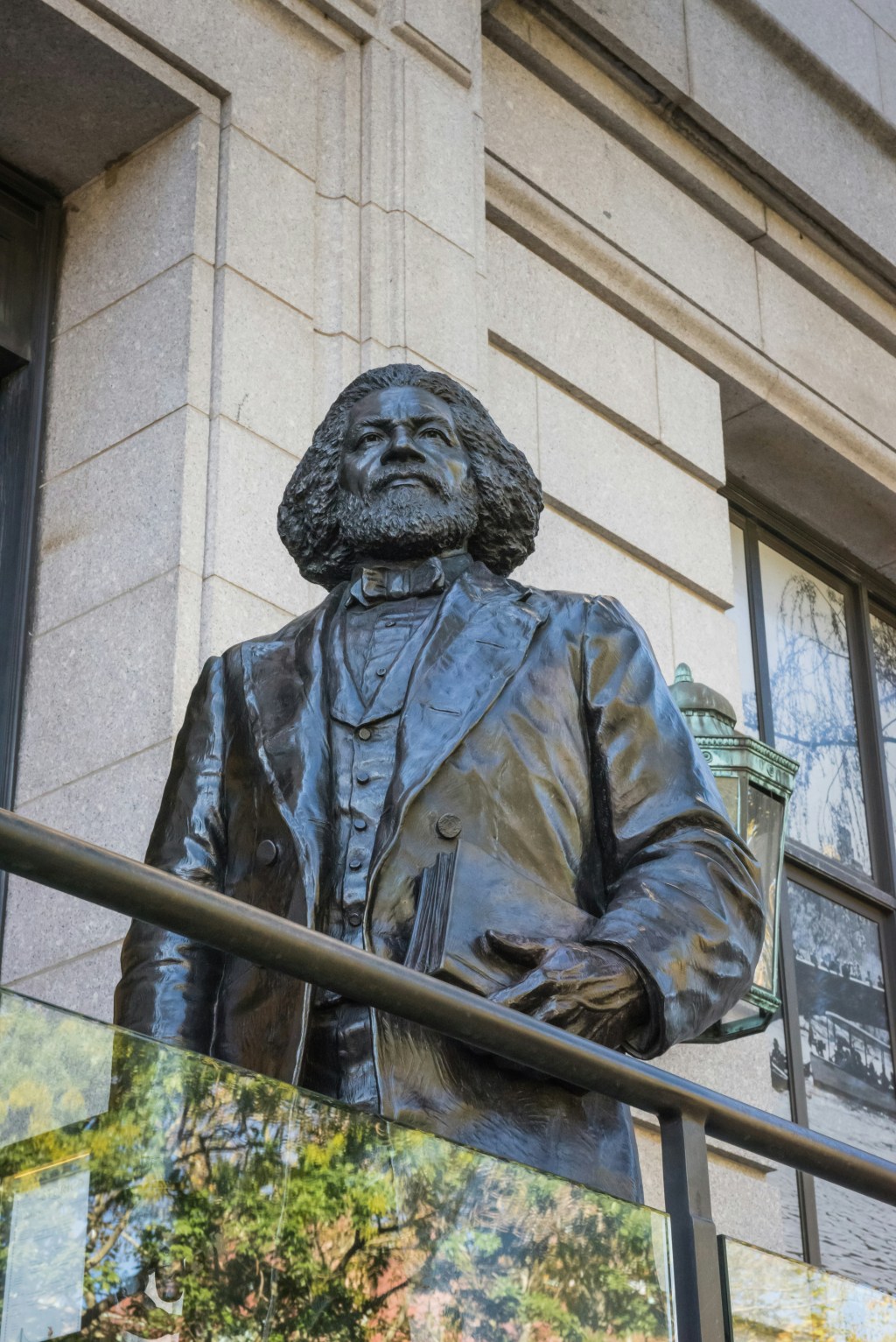

First up: persona. It’s not just about writing—it’s about becoming. How do you craft an identity, project it with swagger, and use it to navigate life’s messiness? When students read Oscar Wilde, Frederick Douglass, or Octavia Butler, they don’t just see words on a page—they see mastery. A fully-realized persona commands attention with wit, irony, and rhetorical flair. Wilde nailed it when he said, “The first task in life is to assume a pose.” He wasn’t joking. That pose—your persona—grows stronger through mastery of language and argumentation. Once students catch a glimpse of that, they want it. They crave the power to command a room, not just survive it. And let’s be clear—ChatGPT isn’t in the persona business. That’s your turf.

Next: ideas. You became a teacher because you believe in the transformative power of ideas. Great ideas don’t just fill word counts; they ignite brains and reshape worldviews. Over the years, students have thanked me for introducing them to concepts that stuck with them like intellectual tattoos. Take Bread and Circus—the idea that a tiny elite has always controlled the masses through cheap food and mindless entertainment. Students eat that up (pun intended). Or nihilism—the grim doctrine that nothing matters and we’re all here just killing time before we die. They’ll argue over that for hours. And Rousseau’s “noble savage” versus the myth of human hubris? They’ll debate whether we’re pure souls corrupted by society or doomed from birth by faulty wiring like it’s the Super Bowl of philosophy.

ChatGPT doesn’t sell ideas. It regurgitates language like a well-trained parrot, but without the fire of intellectual curiosity. You, on the other hand, are in the idea business. If you’re not selling your students on the thrill of big ideas, you’re failing at your job.

Finally: chaos. Most people live in a swirling mess of dysfunction and anxiety. You sell your students the tools to push back: discipline, routine, and what Cal Newport calls “deep work.” Writers like Newport, Oliver Burkeman, Phil Stutz, and Angela Duckworth offer blueprints for repelling chaos and replacing it with order. ChatGPT can’t teach students to prioritize, strategize, or persevere. That’s your domain.

So keep honing your pitch. You’re selling something AI can’t: a powerful persona, the transformative power of ideas, and the tools to carve order from the chaos. ChatGPT can crunch words all it wants, but when it comes to shaping human beings, it’s just another cog. You? You’re the architect.

Thinking about my sales pitch, I realize I should be grateful—forty years of teaching college writing is no small privilege. After all, the very pillars that make the job meaningful—cultivating a strong persona, wrestling with enduring ideas, and imposing structure on chaos—are the same things I revere in great novels. The irony, of course, is that while I can teach these elements with ease, I’ve proven, time and again, to be utterly incapable of executing them in a novel of my own.

Take persona: Nabokov’s Lolita is a master class in voice, its narrator so hypnotically deranged that we can’t look away. Enduring ideas? The Brothers Karamazov crams more existential dilemmas into its pages than both the Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia combined. And the highest function of the novel—to wrestle chaos into coherence? All great fiction does this. A well-shaped novel tames the disarray of human experience, elevating it into something that feels sacred, untouchable.

I should be grateful that I’ve spent four decades dissecting these elements in the classroom. But the writing demon lurking inside me has other plans. It insists that no real fulfillment is possible unless I bottle these features into a novel of my own. I push back. I tell the demon that some of history’s greatest minds didn’t waste their time with novels—Pascal confined his genius to aphorisms, Dante to poetry, Sophocles to tragic plays. Why, then, am I so obsessed with writing a novel? Perhaps because it is such a human offering, something that defies the deepfakes that inundate us.