I should have known at thirteen that seventeen would be brutal. At thirteen, Janis Ian’s “At Seventeen” was already circulating through the house like a prophecy. I liked the song well enough, but my mother loved it. It was her time machine back to high school—loneliness, rejection, the ache of not measuring up. More than once I watched her eyes fill as the song drifted out of our Panasonic portable radio. That was her loneliness anthem. I needed my own. Mine was “Watching and Waiting” by the Moody Blues—a song for someone alone in the dark who senses there is something greater beyond himself and aches to make contact with it. Less teenage rejection, more metaphysical hunger.

By seventeen, starting college, I was profoundly lonely. According to Erik Erikson, this is the stage defined by intimacy versus isolation, and I was losing badly. I felt it in my bones as a socially maladroit bodybuilder shuffling through classes by day and working nights as a bouncer at a teen disco called Maverick’s in San Ramon. Picture it: me at the door, arms crossed, watching a parade of thrill-seekers gyrate, flirt, and dissolve into noise. The job didn’t cure my loneliness; it distilled it. I was close enough to touch the crowd and miles away from belonging to it.

One morning after a late shift, I dreamed I was living in the Stone Age. I was alone in a cave, wrapped in animal skins, stepping out into a gray, indifferent sky. I raised my arms toward the clouds, reaching for something—anything—that might answer me. In the background, “Watching and Waiting” played like a prayer I hadn’t yet learned how to pray. The dream was sad and beautiful, which felt like progress. As Kierkegaard noted, despair’s worst form is not knowing you’re in it. At least I knew. And as the Psalmist understood long before therapy existed, grace tends to follow sorrow once the sorrow has been fully felt.

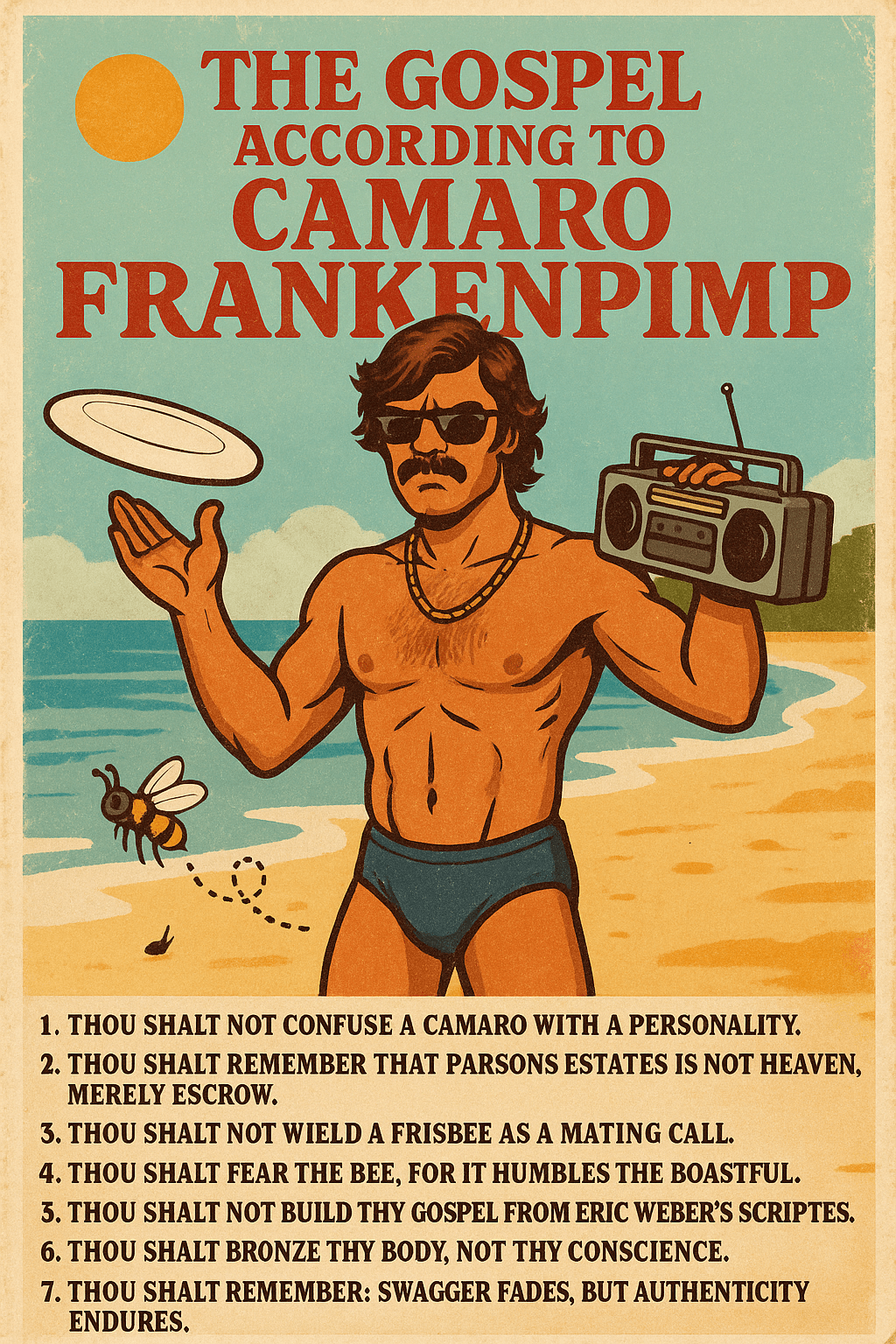

People hate being alone. They’ll sit through ads on YouTube rather than listen ad-free on Spotify because YouTube lets them comment, scroll, argue, agree—experience the song with others. Solitude may be cleaner, but communion is warmer. Which brings me to watches. What is the watch hobby in isolation? Nothing. A watch on a deserted island is just a lump of steel keeping time for no one. The hobby exists only because a community animates it—supports it, debates it, sometimes overfeeds it. A watch on your wrist is a semiotic flare. It says something. Others read it. You read them back. That exchange is the point.

This is what I mean by Horological Communion: the quiet fellowship formed when watches are not hoarded as private trophies but offered as shared symbols. Meaning emerges only when the object is seen, recognized, and answered—at meetups, in forums, in comment sections, across a knowing glance from one wrist to another. Without that communion, the watch is mute. It ticks, faithfully, but it says nothing at all.