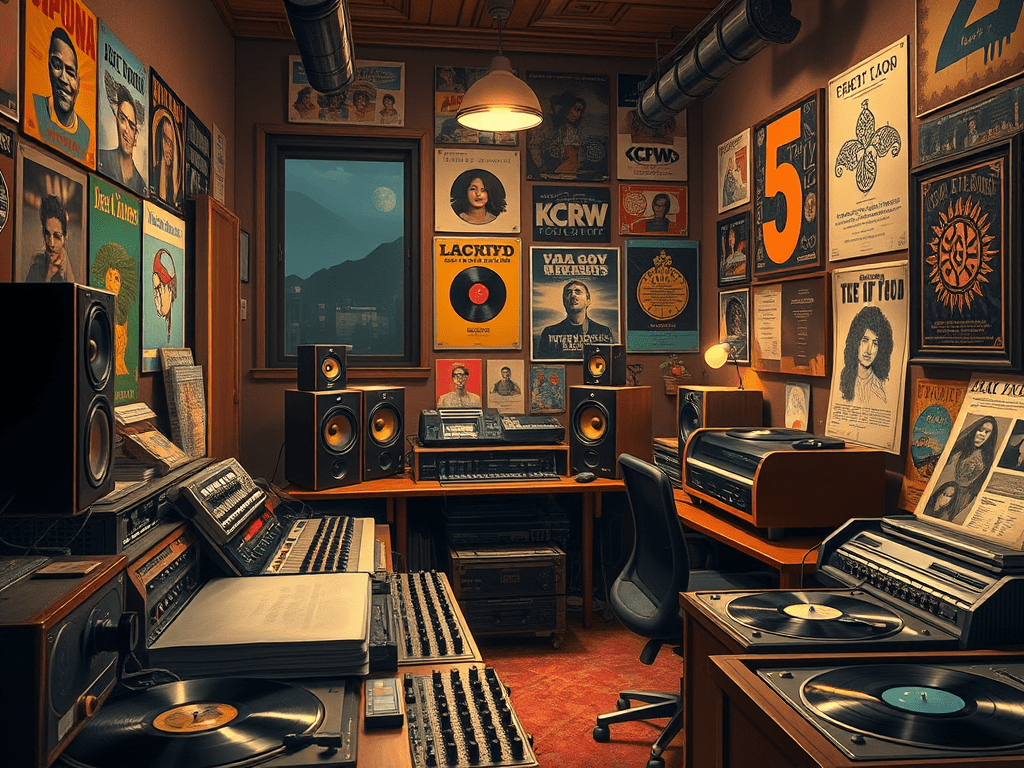

When I think of KCRW in its prime, the vintage frequency that turned Southern California’s airwaves into a velvet groove, I’m back in the 90s and early aughts. That was when the DJs, high priests of cool, dropped Zero 7’s “In the Waiting Line”, Groove Armada’s “At the River,” the Sneaker Pimps’ “6 Underground,” and Kaskade’s “The Wink of an Eye” and “Right Dream.” Those weren’t just songs—they were the soundtrack to Los Angeles itself, the city’s languid sigh in stereo. Back then, KCRW wasn’t just a radio station. It was an oracle of taste, an influencer before “influencers” became a plague, before algorithms strangled the mystery out of music and left us with playlists designed by soulless code.

Category: music

-

Why I’ll Never Be a Normal Tourist

I don’t deserve a nice vacation. Who am I to lounge in tropical paradise, sipping a Miss Sunshine on the rooftop of Tommy Bahama’s in Honolulu—a lemon-infused Grey Goose cocktail dressed up with coconut and salted honey, basically sunshine in a martini glass?

Yet that’s exactly what I did on my last night in town. My family and I ate dinner under the soft glow of string lights while a guitarist named Mark worked the crowd. He had that rare gift of making diners feel the music was just for them. My daughter requested Neil Young’s “Harvest Moon.” Mark delivered it like a love letter. I followed with The Go-Betweens’ “Streets of Our Town.” He’d never heard of it. Then I tried “Back to the Old House” by The Smiths. His eyes lit up.

“Oh, you’re one of those,” he said, as if I’d just flashed a velvet-lined membership card to the Melancholy Music Society. “Are you a musician?”

I admitted to being an amateur pianist. During his break, we talked shop. He’d been gigging since 1979, grew up on Oahu, and had soured on Maui—“negative energy,” he said, with the certainty of a man who’s read the island’s aura. His favorite? The Big Island, especially Hilo. “Hilo’s the lush side,” he told me, as if revealing a secret password.

The next day, stuck in the Honolulu airport waiting for a delayed United flight (short a flight attendant, with a substitute speeding in from home), I met Zack—a 48-year-old professional golf caddy with the leathery tan of someone who spends life between fairways and airports. He was headed to Houston, then on to Kansas City for a tournament at Blue Hills Country Club.

We talked for forty-five minutes about the job. “You have to make a world-class golfer like you, trust you, and win,” I told him. “That’s harder than being a psychiatrist.”

He grinned. “Same as being a college writing instructor.”

Touché. We agreed we were both part salesman, part psychologist.

Zack checked his watch. “If I make my Houston connection, I get Texas brisket with my family before the drive to KC.” His wife taught French at an Oahu high school; they’d lived there over twenty years. Like Mark, he loved the Big Island most. Also like Mark, he worshipped Hilo. In fact, he’d bought land there for his retirement.

On the flight, I lost myself in Jim Bouton’s Ball Four on Audible, forgetting about Zack—until landing, when the flight attendants asked passengers to clear the way for passengers with tight connections. At the back, there was Zach, looking like he’d just played eighteen holes without water.

With the authority of a man who’d just been handed the Staff of Moses, I raised my hand: “Make way for my friend Zack! He has three minutes to make his connection!” The crowd parted. As he hurried past me, I patted his back and told him to enjoy the brisket.

My wife nearly folded in half laughing at my grandiosity, my habit of turning chance encounters into minor epics. At baggage claim, she called Mark and Zack my “new friends.”

She’s right. I may never learn to truly relax on vacation. But give me a stranger with a story, and I’ll make a night of it.

-

Not Just the Way You Are: The Untold Grit of Billy Joel

In high school, I was a sap for Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are”—a sentimental earworm that lodged itself in my adolescent chest like a slow-burning ember of longing. But it was “The Stranger,” with its eerie whistle intro, that truly haunted me. That mournful melody had the same desolate magic as “The Lonely Man Theme” from The Incredible Hulk—the tune that played whenever Bruce Banner had to hitchhike into oblivion with nothing but his duffel bag and repressed rage.

Aside from that one album, though, I had little use for Billy Joel. His music struck me as sonic white bread—palatable, inoffensive, nutritionally empty. I still recall a vicious takedown in The San Francisco Chronicle where a critic dismissed Joel as a budget-bin Beatles knockoff. That assessment dovetailed nicely with my own smug teenage sneer. When a cousin of mine announced in the early ’80s that he was driving to L.A. to see Joel live, I smiled politely and thought, Enjoy your night of mediocrity, friend.

Then the decades rolled by, as they do. Billy Joel fell off my radar completely. Not a note, not a thought, not a twitch of nostalgia. The man might as well have joined Jimmy Hoffa in the cultural vault. But recently, a few podcasters I trust raved about a five-hour documentary—Billy Joel: And So It Goes—streaming on HBO Max. Out of curiosity (and procrastination), I pressed play.

And damn if it didn’t pull me in.

Joel’s life story is a full-blown psychodrama with the pacing of a prestige miniseries. He falls in love with his bandmate’s girlfriend, gets punched in the face when the betrayal surfaces, spirals into suicidal depression, checks himself into a psychiatric hospital, emerges emotionally bruised but determined, and—naturally—marries the very same woman. She becomes his manager. They hit the road. That alone is a screenplay waiting to happen.

The documentary then charts his wreckage-strewn romantic path: four marriages, battles with booze, perfectionism bordering on pathology, and the slow, soul-bruising realization that having half a billion dollars doesn’t guarantee someone to watch movies with on a Sunday night.

Much of Joel’s pain seems to flow from a frigid relationship with his father—a classical pianist who fled Nazi Germany only to land in the capitalist circus of America, which he promptly came to despise. He left for Vienna and left Billy with an emotional black hole for a torso. Joel wrote songs, not for fame, but to fill that void—to wring something warm from cold keys.

His mother didn’t help. She was likely bipolar, and Joel suspects he inherited some version of it—his life a pendulum swing between euphoric crescendos and basement-floor depressions. This emotional volatility didn’t soften him. If anything, Joel is grittier than I ever gave him credit for: a pugnacious Long Islander with a boxer’s jaw and the soul of a saloon poet.

That famously mushy ballad “Just the Way You Are”? He hated it. Thought it was soggy sentimentalism unworthy of an album slot. Only when the band added a Bossa Nova beat did he reluctantly agree to let it stay. And that song, of course, became his most iconic.

I came away from And So It Goes with a new view of Billy Joel—not as a sentimental hack or a Beatles Xerox machine, but as a bruised, brilliant craftsman. He’s not just a hitmaker. He’s a man on fire, trying to warm himself with melodies pulled from the wreckage of his life.

-

If Cormac McCarthy Wrote a Movie Treatment for The Beatles’ “The Long and Winding Road.”

FADE IN:

A road. It winds through the wastes like a serpent that forgot its own name. Cracked earth on either side. Fence posts like grave markers. Vultures in the sky, circling nothing in particular, just keeping warm. A man walks it. His boots are flayed open. His eyes are sunburned. His soul is a blister dragging itself behind him.

His name is Lyle. Or maybe Thomas. The script never says. Doesn’t matter. He’s every man who ever wrote a love letter in blood and mailed it into the void.

He is looking for her. She has no name, just a shape in the distance, a memory braided from perfume and last words. She left him. Maybe twice. Maybe more. He kept the door open. She never knocked.

The road has been long. Winding. Bleak. It led him through dead towns and ghost motels. Once he stayed in a place where the concierge was a buzzard and the minibar held only regret.

He speaks not. The road speaks for him. It says:

Every fool must follow something. You picked hope. Bad draw.

Flashbacks flicker: A woman, face soft as moonlight, eyes like unpaid debt. She tells him she’s leaving. He says he’ll wait. She laughs. That’s the last thing she gives him. Her laughter. Acid-bright and final.

Along the road he meets others—pilgrims of delusion.

One man rides a shopping cart filled with old love songs on cassette.

One woman sews wedding dresses for brides that never were.

One child sells maps to places that no longer exist.

They all walk. They all believe the road leads somewhere. It don’t.

Eventually, Lyle comes upon a house at the end of the road. It is the house. Her house. Or what’s left of it. The windows are boarded. The door is gone. Inside, just dust, a broken phonograph, and a bird trapped in the chimney, fluttering against the soot.

He kneels.

Not to pray. To listen.

There’s no music. No answer. Only wind. And the bird’s soft thump, thump, thump.

He lies down. The road curls around him like a noose.

FADE TO BLACK.

The final line scrolls in silence:

Love didn’t leave. It just stopped answering the door.

-

If Cormac McCarthy Wrote a Movie Treatment for the Bee Gees’ “Fanny (Be Tender With My Love)”

MOVIE TREATMENT: Fanny (Be Tender With My Love)

FADE IN:

Dust plains. Endless. Cattle skeletons sun-bleached and smiling in the dirt. A wind hisses through creosote like it knows a secret. A man rides into this ruin on a horse too tired to live and too dumb to die. His name is Merle. Once a singer. Once a lover. Now a shadow in spurs.

He carries a guitar with one string and a heart torn open like a blister.

He is looking for Fanny.

Fanny of the laugh that could undo a priest. Fanny of the hips that made men renounce geography. Fanny who told him to be strong and then walked out with a mule-skinner named Dutch who wore cologne and shot rattlesnakes for fun.

She left Merle in the middle of a love song.

Now Merle drags that song across the desert like a broken leg.

The locals say Fanny dances at The Rusted Mirage, a bar built on an old mine shaft. It sits at the edge of a dead lake where the water’s gone but the longing remains. Inside, broken men drink varnish and pray to forgotten gods. There’s a jukebox that plays nothing but Bee Gees covers sung by a toothless man in a gold suit. Fanny’s silhouette haunts the stage, flanked by two coyotes who think they’re her backup dancers.

Merle stumbles in like a man arriving at his own funeral. He sees her. She sees him. Silence falls like a noose.

He says

Fanny. Be tender.

She says

Boy you shoulda thought of that when you threw my birthday pie in the fire.

He says

That was an accident.

She says

So was my affection.

They duel. Not with pistols. With ballads. His sorrowful wail versus her falsetto fury. The bartender cries. A dog howls. Someone overdoses on sassafras in the corner.

By dawn, Merle lies collapsed. Empty. She kisses him once—on the temple, like a burial rite. Then disappears into the jukebox, leaving behind only a boa made of scorpion tails and crushed velvet.

FADE OUT.

A narrator, gravel-voiced and full of scorn, speaks:

Love’s a fever dream. Some wake up cured. Some never wake at all.

-

If Cormac McCarthy Wrote a Movie Treatment for Maria Muldaur’s “Midnight at the Oasis”

FADE IN:

A bone-white desert stretches out beneath a black vault of stars. The dunes are still as sacrificial altars. Somewhere out there, beneath the coyote moon and the ruined tower of Orion, rides a woman of indeterminate age and infinite mischief. She wears a sun hat like a halo. Her sandals leave no prints.

The camel she rides is named Jeremiah. He does not speak but regards the world with the mournful gaze of a beast who has seen empires fall and lovers lie. His saddle is adorned with silver conches, turquoise fringe, and a little brass bell that tolls only for the damned.

She comes upon a man.

He is shirtless, jawline like a blade. Smokes roll-your-owns and speaks in aphorisms. Former bluesman turned snake-oil preacher turned fugitive for a crime he may or may not have committed in Santa Fe, where the sheriff’s daughter still dreams of him and leaves milk out for the scorpions.

She says

Midnight at the oasis

He says

There’s no such thing as time in this country. Only heat and forgetting.

They drink wine from a dented canteen and roast cactus blossoms on a fire made of mesquite and ancient regret. The camel chews cud. The stars wheel. A frog laughs somewhere.

The woman suggests they slip off to a sand dune real soon. Her voice, soft as velvet, carries across the salt-swept wind like prophecy or seduction or both. The man, being a fool or a poet (but never both at once), accepts.

The desert is watching. It has watched worse.

They make love like two fugitives hiding from God, beneath constellations older than grammar. Their bodies steam in the moonlight. A lizard judges them and scuttles away.

At dawn, they are pursued. By whom? Perhaps the woman’s husband. Perhaps bounty hunters. Perhaps just Time, wearing spurs and humming a Carter Family tune. The chase is unspoken but certain.

The camel refuses to run.

The woman kisses the man once more and vanishes into a dust devil. Gone. Or maybe never there to begin with.

The man will ride Jeremiah to the nearest roadhouse and order three fingers of mezcal. He will never again look at the moon without suspicion.

FADE TO BLACK.

-

Gene Wilder’s Prelude to Mischief and Mayhem

In fourth grade at Anderson Elementary in San Jose, our teacher cracked open Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and unleashed a literary sugar bomb on the classroom. The characters didn’t just leap off the page—they kicked down the door of our imaginations and set up shop. The book hijacked our brains. Good luck checking it out from the library—there was a waiting list that stretched into eternity.

A year later, the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory hit theaters, but my parents, apparently operating under some moral suspicion of Hollywood whimsy, refused to take me. I wouldn’t see it until the VHS era, when cultural consensus finally upgraded it to “beloved classic” status. That’s when I met Gene Wilder’s Wonka—equal parts sorcerer, satirist, and deranged uncle.

The best moment? Easy. He hobbles out, leaning on a cane like a relic of Victorian fragility—then suddenly drops the act, executes a flawless somersault, and stands up with a gleam that says, I know exactly what game I’m playing, and so should you. That glint in his eye, equal parts wonder and judgment, has haunted me for decades. His entire persona is a velvet-gloved slap to the smug, the spoiled, and the blissfully ignorant. He isn’t just testing children—he’s taking society’s moral pulse and finding a weak, sugary beat.

That gleam stayed with me. So much so that I wrote a piano piece inspired by Wilder’s performance. I called it Gene Wilder’s Prelude to Mischief and Mayhem. The first movement was a nightmare—rewritten more times than I care to admit. Oddly, the second and third movements came first, composed together in the aftermath of my mother’s passing on October 1, 2020. Nearly five years later, I finally completed the first movement, like some strange reverse birth.

The result? A tribute in three acts to the sly grin, the righteous mischief, and the bittersweet brilliance of Gene Wilder—a man who, like the best artists, never let kindness become cowardice or magic become a mask for mediocrity.

-

One Day, One House, No Excuses

This morning, I brewed a pot of delicious Stumptown French roast—molten, bitter, potent—and padded over to my computer feeling dangerously wholesome. A good man with good intentions. Which, of course, is always the start of a problem. I was toying with the idea of living more virtuously: dialing back the animal fat, leaning into tempeh and nutritional yeast, pretending a plant-based diet isn’t just a long goodbye to flavor. You know, the usual summer resolutions—less cheese, more clarity.

Somewhere between the aroma of roasted beans and my first click of the mouse, I felt something resembling courage. Not the real, bare-knuckled kind, but the kind that sneaks in when the house is quiet and you haven’t yet sabotaged yourself with toast. I thought: Gird up thy loins like a man. (Who says that anymore? Besides prophets and people named Chet.) But still, the idea stuck. Maybe I was finally ready to stop flinching and start living with actual conviction—about food, fitness, morality, and cholesterol.

And yet I know myself. Talk is cheap. I have spent years writing grocery lists for lives I never lived. What matters is performance.

Which brings us to today. My summer has officially begun. My wife and teenage daughters are off to Disneyland—a place I regard with the same warmth I reserve for colonoscopies and TikTok. They know this, and mercifully leave me out of the Mouseketeer pilgrimage. Which means: the house is mine.

I have made a pact with myself. Today, I will submit my final grades, mount the Schwinn Airdyne for a 60-minute sufferfest (estimated burn: 650-750 calories, depending on whether I channel Rocky Balboa or Mister Rogers), and I will rehearse my piano composition—tentatively titled Gene Wilder’s Prelude to Mischief and Madness. If all goes well, I’ll record it and upload it to my YouTube channel, where it will be watched by six people and a bot from Belarus.

Alone time is rare in a house shared with twin teenage girls, a wife, and the occasional haunting presence of someone asking what’s for dinner. I daydream of a private studio—soundproofed, monk-like, adorned with a grand ebony Yamaha piano and maybe a faint aura of genius. Instead, I have today: a suburban cosplay fantasy in which I pretend to be a cloistered artist, instead of a middle-aged man in gym shorts wondering if tempeh is as bioavailable as the vegan influencers claim it is.

And yet… it’s enough. Let the performance begin.

-

Becoming Led Zeppelin: A Fan’s Liturgy in Sweat, Hair, and Feedback

In the Bay Area of the 1970s, nothing was more quintessentially American than Led Zeppelin. Not apple pie, not hot dogs, not even fireworks detonating under the banner of freedom on the Fourth of July. No, Led Zeppelin was the national anthem of hormonal turbulence, a sonic passport to lust, rebellion, and ecstatic doom. At the center of this swirling pagan mass stood Robert Plant—shirtless, golden-maned, howling with the tortured elegance of a fallen angel whose job was to make teenagers believe that transcendence came through hips, heartbreak, and hair-whipping.

Plant wasn’t just the house prophet of sexual revolution-era America; he was its prisoner. His voice didn’t just seduce—it ached. It howled. It bled. It was priapism as opera, libido turned operatic suffering. Meanwhile, Hugh Hefner—the so-called high priest of sexual liberation—was a fraud with a bubble pipe. With his crusty cardigan and smug, soft-core smirk, Hefner sold a sterilized fantasy built for TV sitcoms. Robert Plant, by contrast, sounded like he’d clawed his way out of the underworld in leather pants, carrying every orgasm and every regret with him.

In Bernard MacMahon’s Becoming Led Zeppelin, we encounter Plant as the elder beast—still leonine, still mythic. He reclines in a richly shadowed room worthy of Masterpiece Theatre, his face now a craggy relief map of rock’s excesses. The documentary doesn’t dwell on the groupies, trashed hotel rooms, or aquatic legends of infamy. Instead, it gives us the roots: Plant’s soulful debt to Little Richard, Page and Jones’ studio stint with Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger”—that thunderclap of a song that still sounds like someone hurling a piano at the moon. Watching that scene took me straight back to 1973 Nairobi, where my father and I first heard Bassey belt that monster in a theater so loud it felt like the walls were peeling.

There’s archival footage of Zeppelin playing to a crowd that looks less like Woodstock and more like a family reunion gone sideways. Grandmothers clutching their pearls. Children plugging their ears. No one knew what had hit them. This wasn’t just music—it was a mass exorcism.

So no, Becoming Led Zeppelin won’t give you the tabloid filth. It won’t dive into the daisy chain of destruction that came with their rise. But it offers something more interesting: a portrait of a band that didn’t just soundtrack my youth—they were my youth. And Robert Plant, in all his howling, tormented glory, was its golden god of doom.