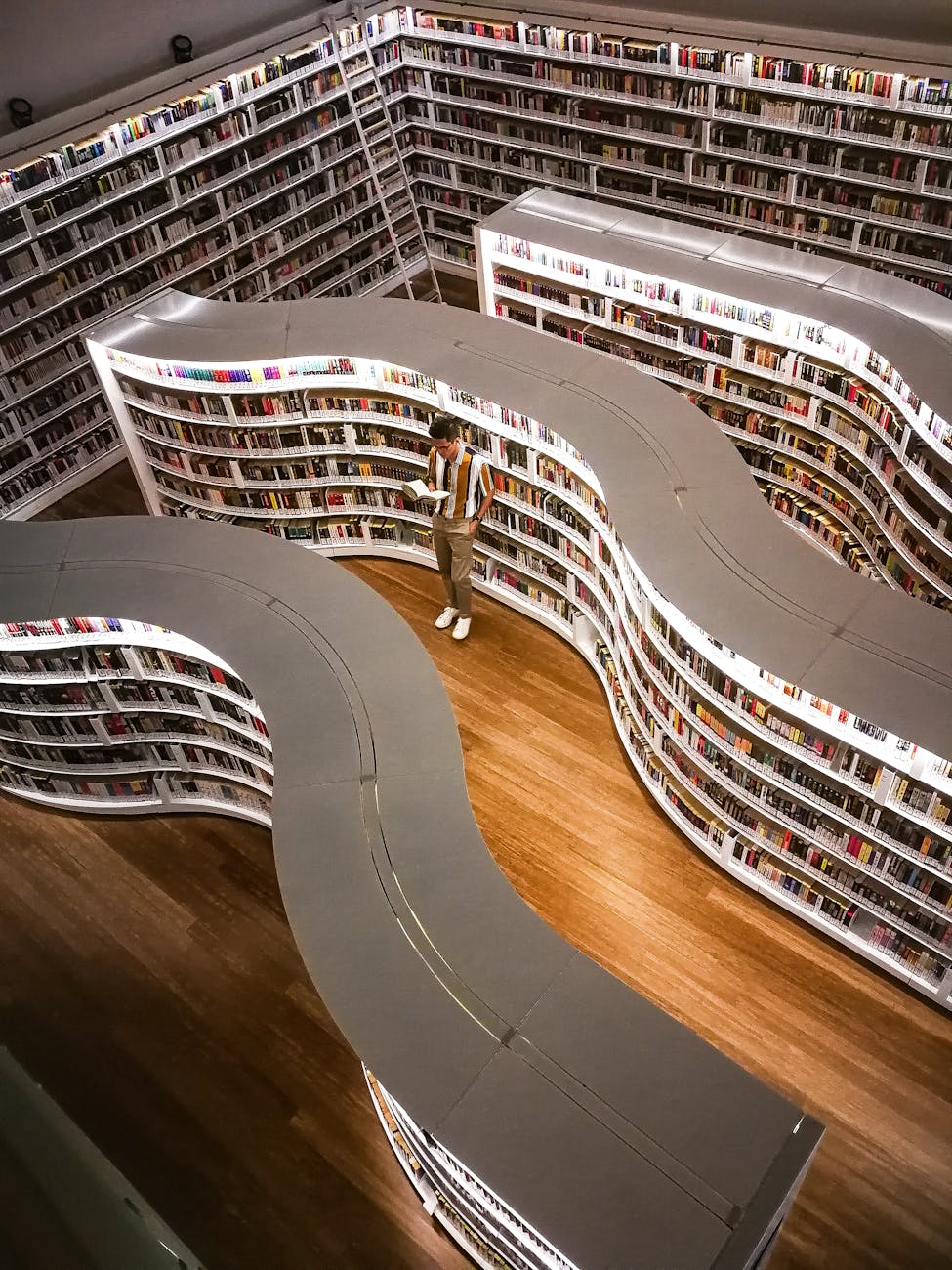

AI is now deeply embedded in business, the arts, and education. We use it to write, edit, translate, summarize, and brainstorm. This raises a central question: when does AI meaningfully extend our abilities, and when does it quietly erode them?

In “The Age of De-Skilling,” Kwame Anthony Appiah argues that not all de-skilling is equal. Some forms are corrosive and hollow us out; some are “bad but worth it” because the benefits outweigh the loss; some are so destructive that no benefit can redeem them. In that framework, AI becomes most interesting when we talk about strategic de-skilling: deliberately off-loading certain tasks to machines so we can focus on deeper, higher-level work.

Write a 1,700-word argumentative essay in which you defend, refute, or complicate the claim that not all dependence on AI is harmful. Take a clear position on whether AI can function as a “bad but worth it” form of de-skilling that frees us for more meaningful thinking—or whether, in practice, it mostly dulls our edge and trains us into passivity.

Your essay must:

- Engage directly with Appiah’s concepts of corrosive vs. “bad but worth it” de-skilling.

- Distinguish between lazy dependence on AI and deliberate collaboration with it.

- Include a counterargument–rebuttal section that uses at least one example of what we might call Ozempification—people becoming less agents and more “users” of systems. You may draw this example from one or more of the following Black Mirror episodes: “Joan Is Awful,” “Nosedive,” or “Smithereens.”

- Use at least three sources in MLA format, including Appiah and at least one Black Mirror episode.

For your supporting paragraphs, you might consider:

- Cognitive off-loading as optimization

- Human–AI collaboration in creative or academic work

- Ethical limits of automation

- How AI is redefining what counts as “skill”

Your goal is to show nuanced critical thinking about AI’s role in human skill development. Don’t just declare AI good or bad; use Appiah’s framework to examine when AI’s shortcuts lead to degradation—and when, if used wisely, they might lead to liberation.

3 building-block paragraph assignments

1. Concept Paragraph: Explaining Appiah’s De-Skilling Framework

Assignment:

Write one well-developed paragraph (8–10 sentences) in which you explain Kwame Anthony Appiah’s distinctions among corrosive de-skilling, “bad but worth it” de-skilling, and de-skilling that is so destructive no benefit can justify it.

- Use at least one short, embedded quotation from Appiah.

- Paraphrase his ideas in your own words and clarify the differences between the three categories.

- End the paragraph by briefly suggesting how AI might fit into one of these categories (without fully arguing your position yet).

Your goal is to show that you understand Appiah’s framework clearly enough to use it later as the backbone of an argument.

2. Definition Paragraph: Lazy Dependence vs. Deliberate Collaboration

Assignment:

Write one paragraph in which you define and contrast lazy dependence on AI and deliberate collaboration with AI in your own words.

- Begin with a clear topic sentence that sets up the contrast.

- Give at least one concrete example of “lazy dependence” (for instance, using AI to dodge thinking, reading, or drafting altogether).

- Give at least one concrete example of “deliberate collaboration” (for instance, using AI to brainstorm options, check clarity, or off-load repetitive tasks while you still make the key decisions).

- End the paragraph with a sentence explaining which of these two modes you think is more common among students right now—and why.

This paragraph will later function as a “conceptual lens” for your body paragraphs.

3. Counterargument Paragraph: Ozempification and Black Mirror

Assignment:

After watching one of the assigned Black Mirror episodes (“Joan Is Awful,” “Nosedive,” or “Smithereens”), write one counterargument paragraph that challenges the optimistic idea of “strategic de-skilling.”

- Briefly describe a key moment or character from the episode that illustrates Ozempification—a person becoming more of a “user” of a system than an agent of their own life.

- Explain how this example suggests that dependence on powerful systems (platforms, algorithms, or AI-like tools) can erode self-agency and critical thinking rather than free us.

- End by posing a difficult question your eventual essay will need to answer—for example: If it’s so easy to slide from strategic use to dependence, can we really trust ourselves with AI?

Later, you’ll rebut this paragraph in the full essay, but here your job is to make the counterargument as strong and persuasive as you can.