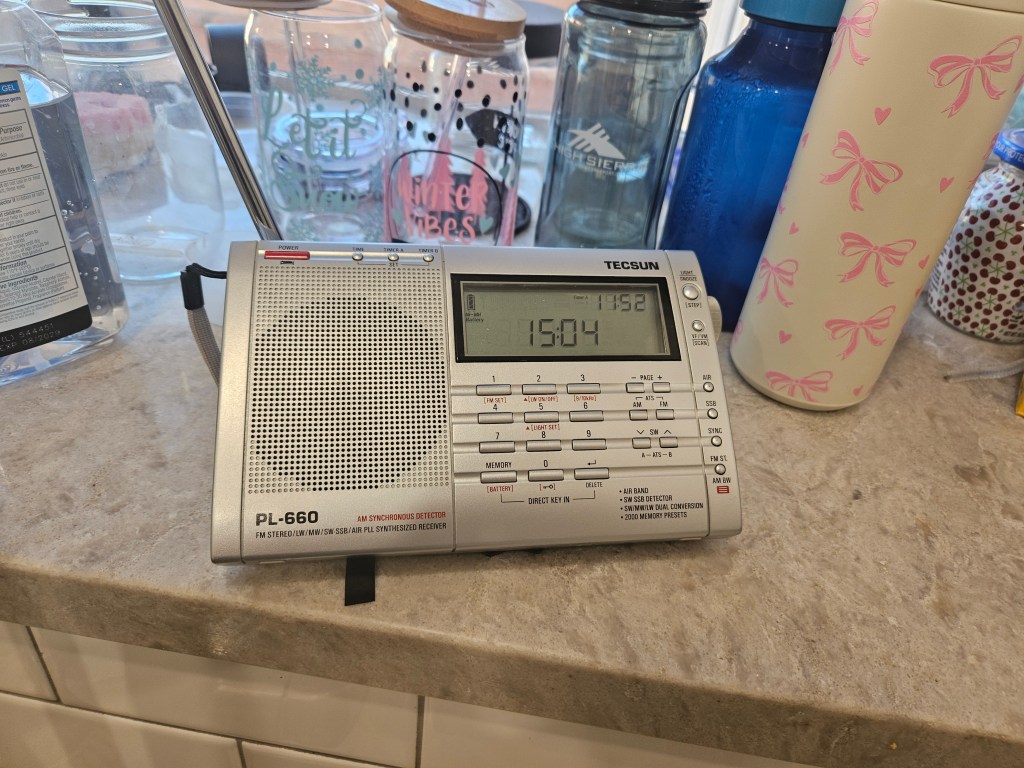

I picked up an open-box Tecsun PL-680 for a huge discount, a deal too good to resist. Did I need it? Absolutely not. I already own the Tecsun PL-660, its near-identical twin. But this wasn’t a rational purchase—this was a radio-fueled nostalgia binge, a return to my obsession from 15 years ago. I love these radios. I love their design, their buttons, their retro Cold War aesthetic. And let’s be honest—I just wanted to compare them.

First Impressions:

I expected to prefer the PL-660’s design, but the PL-680 surprised me. It has a slightly different look, and now that I have both, I can’t pick a favorite. They’re like fraternal twins with great reception and a questionable resale value.

Performance Check:

- AM/FM Reception? Identical—stellar sensitivity, fantastic clarity, and minimal RFI (unlike my finicky DSP radios).

- Speaker Sound? Nearly indistinguishable, though the PL-680 might have a hair more output—but if you blindfolded me, I doubt I could tell the difference.

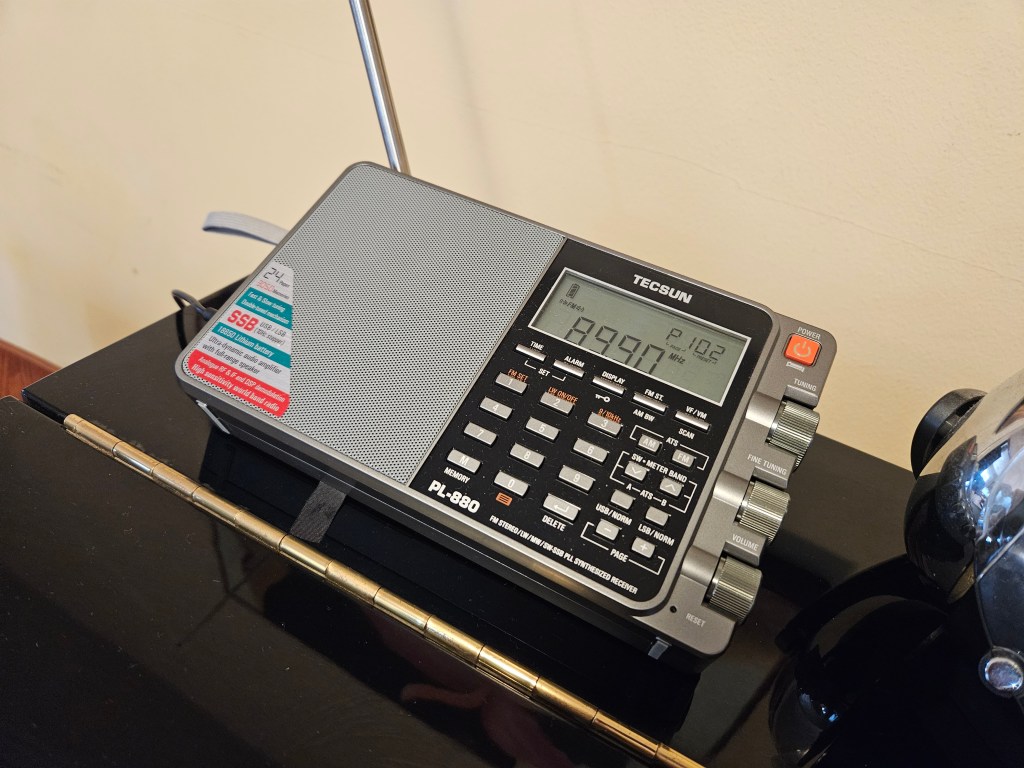

- Compared to My Tecsun PL-880 & PL-990? Not even close—those two have the richer, fuller audio these models lack.

The Unexpected Revelation:

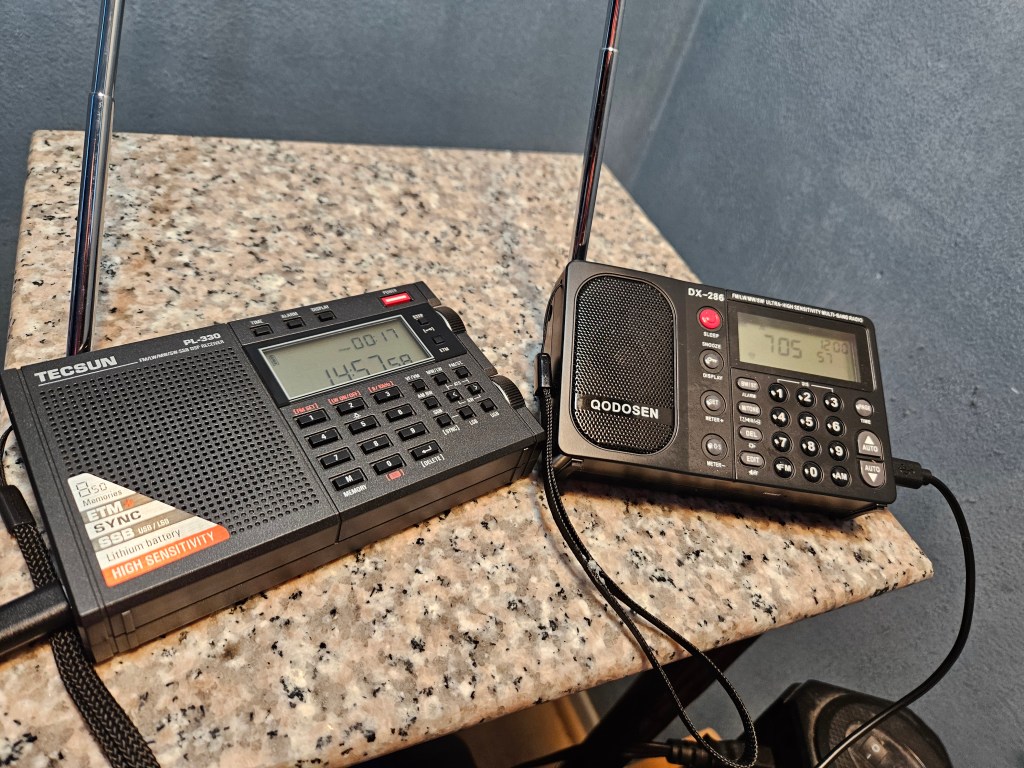

Now here’s where things get weird—the Qodosen DX-286, a smaller, less expensive radio, outshines them in speaker quality. It sounds richer, deeper, fuller, like it’s punching out a solid 3 watts of audio muscle compared to the 1-watt Tecsuns. Suddenly, I found myself fantasizing about a “Super Qodosen”—a 10-watt speaker beast, with a sturdy kickstand and a 7.5-inch chassis, like the Tecsun 660 and 680. If someone built that, I’d throw money at it immediately.

Do I Prefer the Qodosen Overall?

The short answer is no. Its short telescopic antenna can limit FM in some areas of the house and other owners tell me it really shines with an elongated FM antenna, which fits in the 3.5mm jack. This is inconvenient for some.

Also, I’ve learned that I can enjoy the speaker sound on both the 660 and 680 by turning the Treble/Bass switch to Bass, a personal preference.

Buyer’s Remorse?

Not a chance. These are legendary performers, and more importantly, they’re relics of my Radio Obsession 1.0 days. Nostalgia, curiosity, and a good deal—that’s all the justification I need.

Update:

After a month of comparing the two, I much prefer the 660 because the 680 fades in and out of LAist 89.3 causing huge volume fluctuations. I don’t have this problem with the 660. I’m using the 680 in my garage for my kettlebell workouts and close to the outside parkway, the clear reception helps the 680 so I don’t get those volume fluctuations.