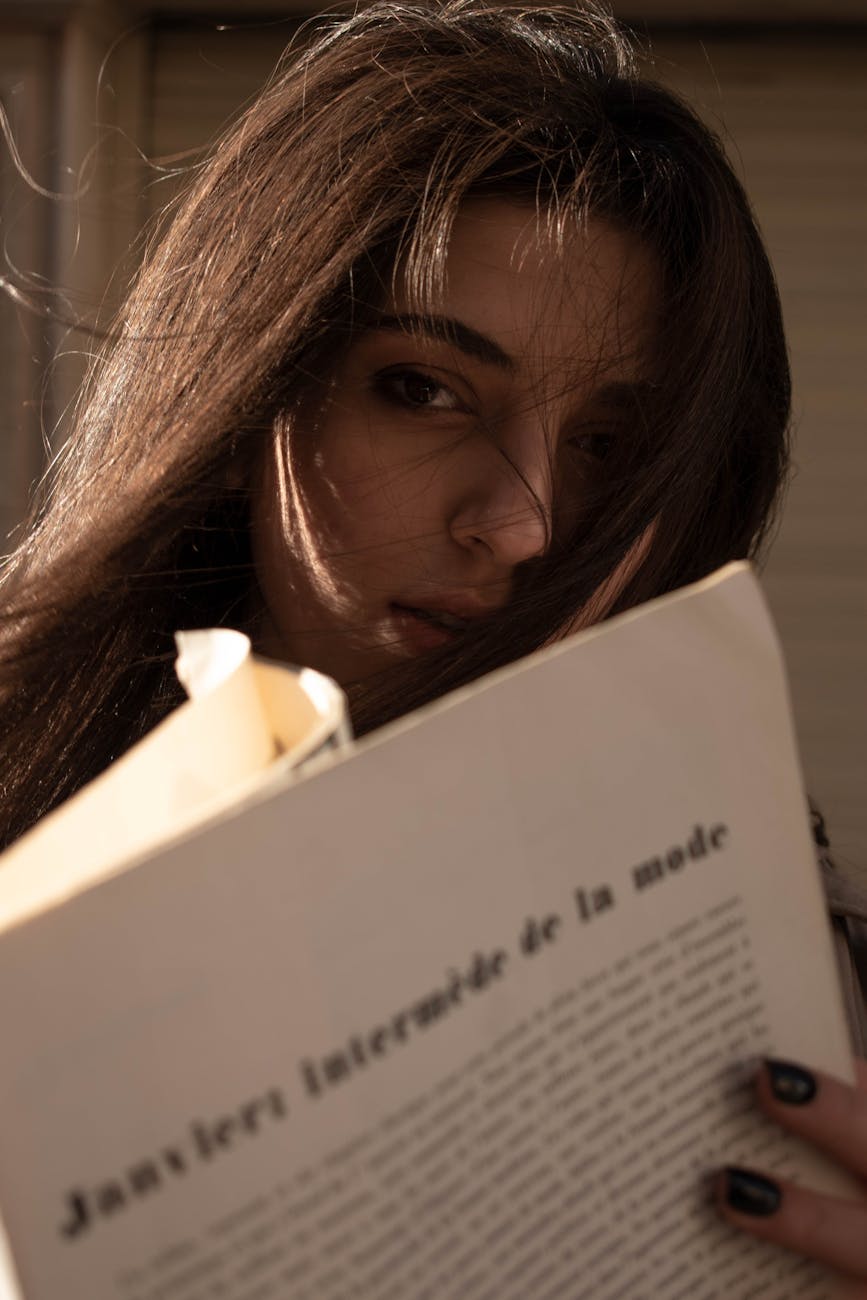

In “Ebooks Are an Abomination,” Ian Bogost delivers a needed slap across the face of our collective reading habits. His charge is simple and devastating: ebooks haven’t expanded reading—they’ve hollowed it out. People believe they’re reading because their eyes are sliding across a screen, but most of what’s happening is closer to grazing. The scandal isn’t that we skim; it’s that we’ve started calling skimming “reading” and don’t even blush. Bogost nails the fraud when he points out that the word reading has become a linguistic junk drawer—used to describe everything from doomscrolling Instagram captions to actually wrestling with dense prose. If the same word covers both scanning memes and grappling with Dostoevsky, then the word has lost its spine.

It reminds me of people who announce they’re going to the gym to “work out.” That phrase now covers a heroic range of activity—from Arnold-style flirtations with death to leaning on a treadmill while watching Jeopardy! and gossiping about coworkers. Same building, radically different realities. One is training. The other is loitering with athletic accessories.

Reading and working out have this in common: they are not activities so much as states of engagement. And the more soaked we become in technology, the more that engagement drains away. Technology sells convenience and dependency—the kind where you feel faintly panicked if you’re five feet from a device and not being optimized by something. But being a reader is the opposite of that nervous dependence. It’s happy solitude. It’s the stubborn pleasure of being absorbed by a book, of sinking into hard ideas—the epistemic crisis, substitutionary atonement, moral ambiguity—without needing an app to pat you on the head and tell you how you’re doing. Real readers don’t need dashboards. Real lifters don’t need Fitbits. If you’re truly engaged, you feel the work in your bones.

And yet technology keeps whispering the same seduction: optimization. Track it. Measure it. Quantify it. But what this gospel of efficiency often delivers is something uglier—disengagement dressed up as progress, laziness rebranded as smart living. The name for this decay is Engagement Dilution: the slow thinning of practices that once demanded effort—reading, training, thinking—into low-grade approximations that still wear the old labels. What once meant immersion now means mere exposure. We haven’t stopped doing these things. We’ve just stopped doing them seriously, and we’re calling that evolution.

To help you interrogate the effects of Engagement Dilution, you will do the following writing prompt.

600-Word Personal Narrative That Addresses Engagement Dilution

We live in an age where everything looks like participation—but very little feels like engagement. We “read” by skimming. We “work out” by standing near machines. We “study” by copying and pasting. We “connect” by reacting with emojis. The actions remain, but the depth is gone. This condition has a name: Engagement Dilution—the process by which practices that once demanded sustained attention, effort, and presence are thinned into low-effort versions that keep the same labels but lose the same meaning.

For this essay, you will write a 600-word personal narrative about a time when you realized you were going through the motions without being truly engaged. Your story should focus on a specific experience in which you believed you were participating in something meaningful—school, work, fitness, relationships, creativity, reading, faith, activism, or personal growth—only to later recognize that what you were doing was a diluted version of the real thing.

Begin with a concrete scene. Put the reader inside a moment: a classroom where you nodded but didn’t think, a gym session where you scrolled more than you lifted, a relationship where you listened with your phone in your hand, a book you “read” but can’t remember, a goal you claimed to care about but never truly invested in. Use sensory detail—what you saw, heard, felt, avoided—to make the dilution visible. Don’t explain the idea yet. Show it happening.

Next, introduce the realization. When did it dawn on you that something essential was missing? Was it boredom? Frustration? Guilt? Emptiness? Did someone confront you? Did you fail at something you thought you had prepared for? Did you suddenly notice how different real engagement feels—how tiring, how uncomfortable, how demanding it is compared to the easy version you had settled for?

Then widen the lens. Reflect on why engagement diluted in the first place. Was it technology? Fear of failure? Desire for comfort? Pressure to appear productive? Lack of confidence? The culture of optimization? Be honest here. Avoid blaming abstract forces alone. This essay is not about what society did to you; it is about the choices you made within that environment.

Finally, confront the cost. What did engagement dilution take from you? Skill? Confidence? Meaning? Relationships? Momentum? And what did it teach you about the difference between looking active and actually being alive inside your actions? End not with a motivational slogan but with clarity—what you now recognize about effort, attention, and the price of avoiding difficulty.

Guidelines

• This is a narrative, not a sermon. Let the story do the thinking.

• Avoid clichés about “finding balance” or “doing better next time.”

• Do not turn this into a tech rant or a productivity essay. Keep it human.

• Use humor if it fits—but don’t hide behind it.

• Your goal is not self-improvement branding. Your goal is insight.

What this Essay Is Really About

Engagement Dilution is not laziness. It is the quiet substitution of comfort for commitment, convenience for courage, motion for meaning. Your task is to show how that substitution happened in your own life—and what it revealed about what real engagement actually costs.

Write the essay only you could write. The more specific you are, the more universal the insight becomes.