It was a Friday night at Castro Valley High, that weekly pageant of teenage aggression disguised as school spirit. The bleachers were packed with hormonal thunder; the air reeked of nacho cheese and Axe body spray. And then the rain came, that democratic force that flattens everyone’s hair and dignity alike.

Across the stands, I saw her—the girl the boys called Tasmanian Devil. I didn’t know her name. No one did. She was a broad-shouldered girl with a face that inspired the cruel kind of laughter—the kind that hides insecurity behind volume. Her twin brother was in the special ed class with her, and their father, the school’s enormous janitor, lumbered around campus in denim overalls so faded they looked ghostly. His ears were so large they could have doubled as warning flags—and he had passed them on to his children, a hereditary curse of ridicule.

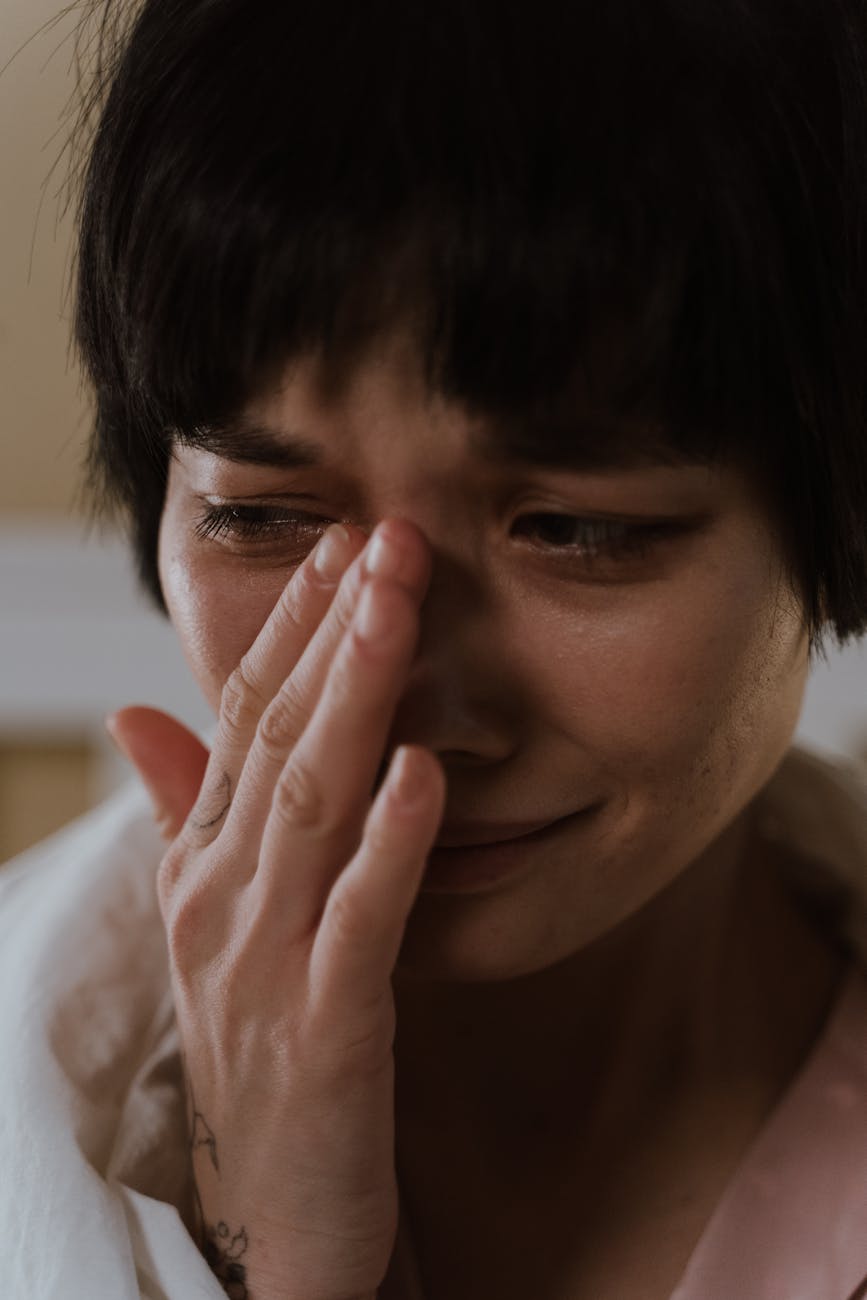

They lived in a trailer next to the football field, an eternal reminder that some people never get to leave campus. That night she sat alone in the bleachers while the rain came down in cold, merciless sheets. Her hair clung to her forehead like seaweed, and black mascara streamed down her face like ink from a wounded pen.

She stared out at the field with a look that broke something inside me—a look that said, I know the joke, and I know I’m the punchline. I know no one will ever love me, and I will always be an outsider.

I wanted to call her over, to hand her my jacket, to do anything that resembled decency—but I did nothing. I sat there with my friends, pretending to watch the game, while she drowned in rain and loneliness.

That night, guilt chewed through me like battery acid. I told Master Po about it—my silence, my self-loathing.

“Master Po, I can’t forgive myself for doing nothing.”

He looked at me the way only the wise can—equal parts compassion and indictment.

“Grasshopper,” he said, “being angry with yourself achieves nothing. Flogging yourself achieves nothing. Shoveling hatred over yourself achieves nothing. If you wish to help those who have no place in this world, you must first make peace with yourself. The wise help others not because they are saints, but because they are whole.”

I lay awake that night thinking about the girl in the rain—how she seemed to know her fate, and how I had rehearsed mine: a spectator of suffering, paralyzed by self-awareness. It was the night I learned the cruelest sin isn’t mockery. It’s inaction dressed up as reflection.