In The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity, Hyam Maccoby doesn’t treat Paul as a saintly architect of faith. Instead, he brands him a slick opportunist — a theological con artist who sidelined Jesus’ Jewish disciples and reinvented the movement to glorify himself. In Maccoby’s telling, Paul isn’t the earnest apostle of Sunday school murals; he’s a résumé-padding religious entrepreneur with a flair for self-promotion.

Luke, author of Acts, doesn’t escape scrutiny either. To Maccoby, Luke plays the role of breathless publicist, polishing Paul into a heroic Hollywood lead — all charisma, no contradictions, halo firmly secured with narrative glue.

Yet as I reread Maccoby, I can’t ignore the irony: in exposing Paul’s myth-making, Maccoby may be engaged in his own. If Luke sculpted Paul into a glowing protagonist, Maccoby chisels him into a grand villain — less apostle, more Bond antagonist with holy stationery.

My relationship with Paul is messier than either portrait. At times he reads like a puffed-up moralist enthralled by his own authority; at other moments, he achieves startling spiritual clarity — like his definition of God as self-emptying love in Philippians. Myth-making, whether heroic or malicious, flattens figures like Paul into cardboard cutouts, sanding down the contradictions that make real people aggravating, compelling, and occasionally profound.

So while Maccoby offers a seductive, neatly packaged explanation for Christianity’s break from Judaism — Paul scheming his way to divine stardom — it feels too tidy. Real history rarely sticks to clean villain-hero binaries.

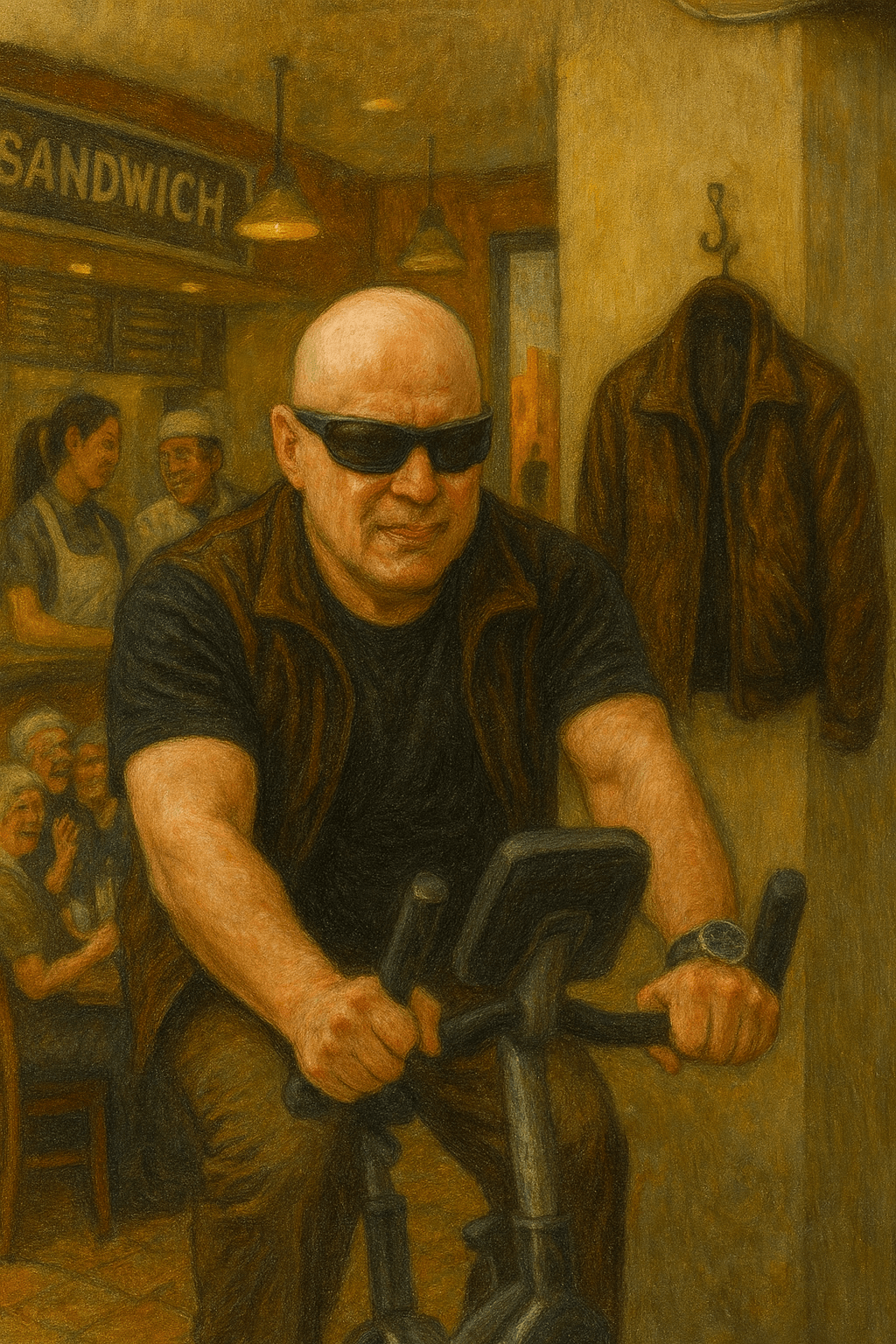

My life would be defined by resolution and an ability to move on if I could see Paul that way Maccoby does, but before I can toss Paul into the narcissist bin and slam the lid, I have to admit that Maccoby — like Luke — might be seduced by narrative neatness. Paul’s letters show someone less like a cartoon schemer and more like a man painfully aware of his own weakness, insecurity, and failure. If he were a megalomaniac mastermind, he was spectacularly bad at the role: beaten, jailed, mocked, shipwrecked, chronically ill, and constantly sparring with congregations who treated him not like a guru but like the world’s most irritating substitute teacher. His theology isn’t the product of a slick PR machine; it reads like a bruised mystic wrestling with power, ego, and surrender.

You can see it in Paul’s grudging boasts, his trembling confessions, and his moments of ecstatic humility — that strange mix of cosmic ambition and self-annihilation that marks someone grappling with God, not angling for a corner office.

It may be comforting to imagine Paul as either saint or sociopath, but the textual record points to something far more inconvenient: a brilliant, exasperating, self-contradicting human being who stumbled toward transcendence while dragging his flaws behind him like rattling tin cans tied to a wedding bumper.

In any event, I shall continue rereading Maccoby. His strident reaction to Paul continues to fascinate me.