In Black Mirror’s “Joan Is Awful,” Charlie Brooker offers more than a dystopian farce—he serves up a wickedly accurate satire of the curated lives we present online. It’s not just Joan who’s awful. It’s us. All of us who’ve filtered our flaws, outsourced our personalities to engagement metrics, and whittled ourselves down to algorithm-friendly avatars. The episode doesn’t critique Joan alone—it roasts the whole rotten architecture of social media curation and shows, with brutal clarity, how the pursuit of digital perfection transforms us into insufferable parodies of our former selves.

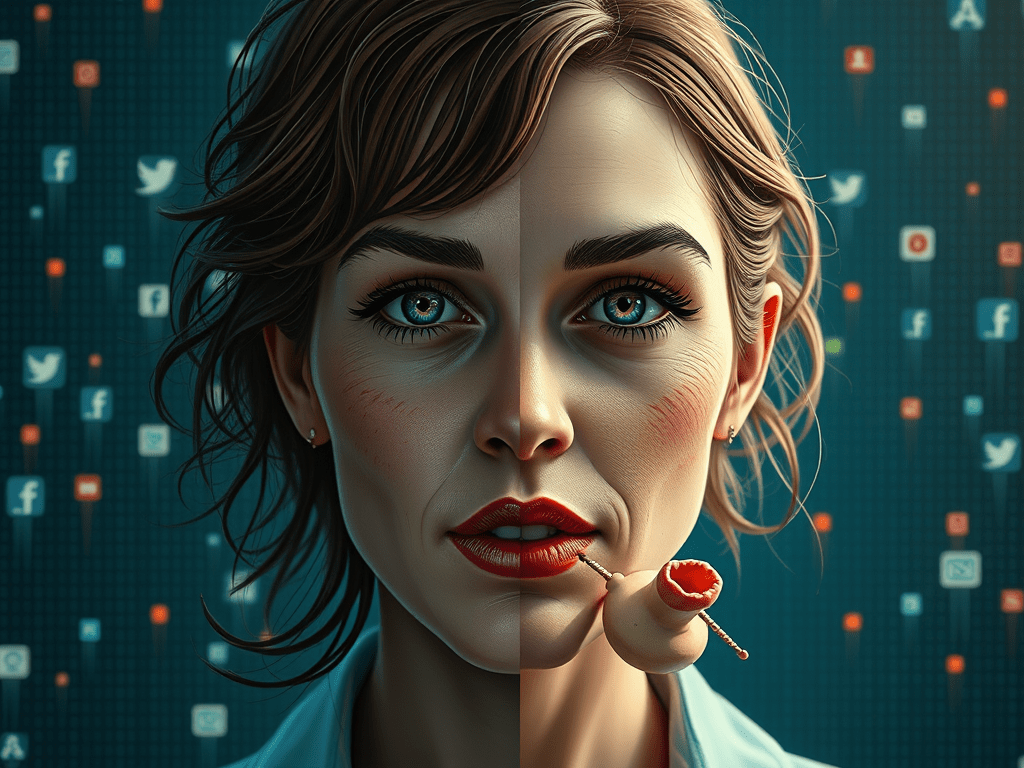

First, let’s talk about performance. Joan, like any good social media user, lives her life as if auditioning for a role she already occupies—one shaped not by authenticity but by optics. She performs “relatable misery,” complete with awkward office banter, fake smiles, and passive-aggressive salad orders. Social media rewards this pantomime, demanding we be palatable, aspirational, and vaguely miserable all at once. The result? A version of ourselves designed to please an audience we secretly resent. Joan is what happens when your curated self becomes the dominant narrative—when branding overtakes being. Her AI-generated counterpart doesn’t misrepresent her; it distills her curated contradictions into a grotesque caricature that somehow feels… accurate.

Second, there’s the fact that Joan—like all of us—is under constant surveillance. In Joan Is Awful, it’s not just the NSA snooping in the background—it’s the entire viewing public, binge-watching her daily descent into algorithm-approved degradation. This is what we’ve signed up for with every “I accept” click: to become content, voluntarily and irrevocably. Our data, behaviors, and digital crumbs are fed into the algorithmic sausage grinder, and what comes out is a grotesque mirror held to our worst instincts. The AI Joan is not a stranger; she’s the monster we’ve been molding through every performative tweet, selfie, and humblebrag. In a world where perception is currency, she’s our highest-valued coin.

Then comes the psychological shrapnel: identity fragmentation. Joan can no longer tell where she ends and Streamberry’s Joan begins, just as many of us can’t quite remember who we were before the algorithm gave us feedback loops in the form of likes, retweets, and dopamine pings. This curated self isn’t just a mask—it becomes the default setting. The dissonance between public persona and private truth breeds an existential malaise. Joan’s real tragedy isn’t that her life is on TV—it’s that she’s lost the plot. She’s a passenger in her own narrative, outsourced to a system that rewards spectacle over substance.

Let’s not forget the moral rot. Watching your AI double destroy your reputation while millions tune in might seem horrifying—until you remember we do this willingly. We doomscroll, rubberneck scandals, and serve our digital idols on platters made of hashtags. Joan, sitting slack-jawed in front of her TV, is no different from us—addicted to her own collapse. It’s not the horror of exposure that eats her alive; it’s the realization that her own worst self is exactly what the algorithm wanted. And that’s what it rewarded.

Ultimately, Joan Is Awful is a break-up letter with social media—if your ex were a manipulative narcissist with access to all your personal data and a flair for psychological torture. Escaping the curated self, as Joan tries to do, is like fleeing an abusive relationship. You know it’s toxic, you know it’s killing you—but part of you still misses the attention. The episode doesn’t end with a triumphant reinvention; it ends with Joan in fast food purgatory, finally unplugged but still wrecked. Because once you’ve sold your soul to the algorithm, the buyback price is steep.

So yes, Joan is awful. But only because she reflects what happens when we let the curated life take the wheel. In the Streamberry age, we aren’t living—we’re streaming ourselves into oblivion. And the worst part? We’re giving it five stars.