For three months I slogged through shoulder pain armed with nothing but a self-diagnosis and stubborn pride. I refused to see a doctor. Why submit myself to some exhausted clinician who’d never lifted a kettlebell in his life and would prescribe the usual pablum—ice, rest, and advice I could have gotten from the comments section of Wikipedia?

Then something happened that forced a reckoning. To compensate for the kettlebell exile, I doubled down on the Schwinn Airdyne—hour-long sessions of fan-bike misery that combine pedaling with lever rowing. I felt no pain… until a week before Thanksgiving. After a brutally satisfying session, a nerve fired down my arm like a live wire. The message was unmistakable: I had graduated from “irritation” to “we’re-squeezing-your-spinal-cord-for-fun.” Something was pinched, something was furious, and it was no longer optional.

I made a YouTube video to announce the cosmic irony: my watch addiction was cured, but the cure was a torn rotator cuff. The floodgates opened. Dozens of comments poured in from people who had endured surgeries, magnets, injections, cortisone cocktails, or endless physical therapy. One old friend emailed: ten years of chronic pain, zero recovery, restricted motion for life. The road, it turns out, is paved with hope and ends in a ditch.

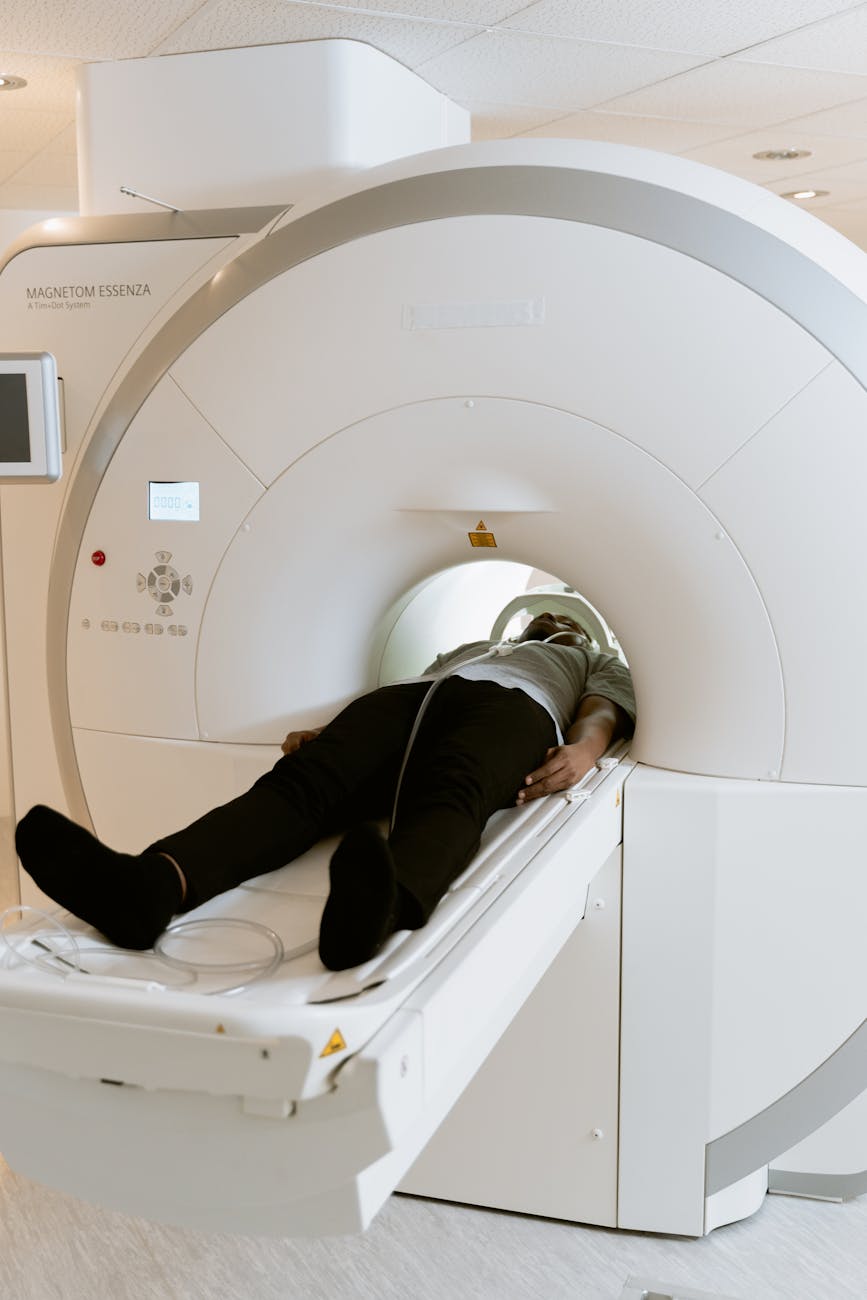

It was clear: I didn’t need more voices, I needed data. I called Kaiser and booked an appointment. Someone would see me the day before Thanksgiving.

That afternoon I met Dr. Cherukuri, a woman in her late thirties with the energy of someone who actually likes her profession. She examined my shoulder, commented that the bulge was visible even through my T-shirt, pressed around the joint, put me through a series of movements, and diagnosed left rotator cuff syndrome with left biceps tendinopathy. She ordered X-rays and an ultrasound and, pending results, believed three months of rehab could put me back together.

She put me on Motrin three times a day for two weeks to bring the inflammation down—enough to make rehab possible. She also agreed I should continue kettlebell work for muscle maintenance. A doctor who understands the importance of preserving muscle mass? I nearly wept. The catch was predictable: no chest or shoulder presses, no biceps curls. My hypertrophy would be confined to legs, glutes, traps—maybe some trickle-down gains from rehab exercises if the gods were kind.

She handed me a list of movements, which I combined with ones I learned from YouTube: cow-cat yoga pose, broomstick flexion, wall push-ups, wall flexion, forearm planks, plank shoulder taps, narrow-position knee push-ups, light dumbbell rotations, and more. Anything that required me to lift my arms overhead or behind me felt like sticking my shoulder into a hornet nest.

The mandate was fifteen minutes of rehab every day. On kettlebell days, I’d slip the movements between lifts three days a week. The other four days were rehabilitation only—an entire week built around mending the wounded joint.

Psychologically, the appointment was a relief. First, the diagnosis proved I wasn’t a lunatic or some melodramatic malingerer. Second, I needed structure. I needed a plan, a weapon—something to push against instead of drifting through pain, anxiety, and the unknowable. When I’m saddled with a problem, I don’t need platitudes; I need targets and artillery. Seeing the doctor was the moment I picked up a rifle instead of a white flag.

But I was still blind. I had no idea how severe the tear was, whether rehab would work, whether I could heal without surgery, or how to navigate the distress of shoulder pain so sharp that turning my steering wheel wrong or sliding a backpack strap across my arm sent shockwaves that lingered for minutes.

Going to a doctor was a necessary first step. But I still knew nothing. All I understood was how much I still needed to know if I hoped to climb out of this hole. The thirst for clarity, for diagnostic certainty, became my new obsession—one that bulldozed my watch addiction.

My YouTube followers were devastated.

“We need you back, bro. We need you to commiserate with us about the watch madness.”

God bless them. They needed me to get better—not only for me, but for them, so we could suffer together in peace.