I grew up in VA housing, transplanted army barracks rebadged “Flavet Villages,” in Gainesville, Florida. The barracks were close to an alligator swamp and a forest where a Mynah bird was always perched on the same tree branch so it was a favorite pastime before bedtime for my father and me to visit the bird on the edge of the forest and converse with it. At dusk, there was a low tide so the alligator dung was particularly pungent. While the smell repelled most, I found the strong aroma strangely soothing and stimulating in a way that made me feel connected to the universe. One evening while my father and I visited the Mynah bird, we could hear a distant radio playing “Bali Ha’i,” sung so beautifully by Juanita Hall. From the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific, “Bali Ha’i” is about an island paradise that seems so close but always remains just out of reach by those who are tantalized by it, causing great melancholy. But I suffered no such melancholy. Paradise was in my presence as my father and I stood by the enchanted forest and spoke to the talking Mynah bird.

The ache of an elusive paradise didn’t afflict me until I discovered I Dream of Jeannie in 1965. The blonde goddess Barbara Eden lived in her genie bottle, a luxurious enclosure with a purple circular sofa lined with pink and purple satin brocade pillows and the inner wall lining of glass jewels shining like mother of pearl. More than anything, I wanted to live inside the bottle with Jeannie. To be denied that wish crushed me with a pang of sadness as deeply as Juanita Hall’s rendition of “Bali Ha’i.” That Jeannie’s bottle was in reality a painted Jim Beam Scotch Whiskey decanter speaks to the intoxication I suffered from my incessant dreams of Barbara Eden.

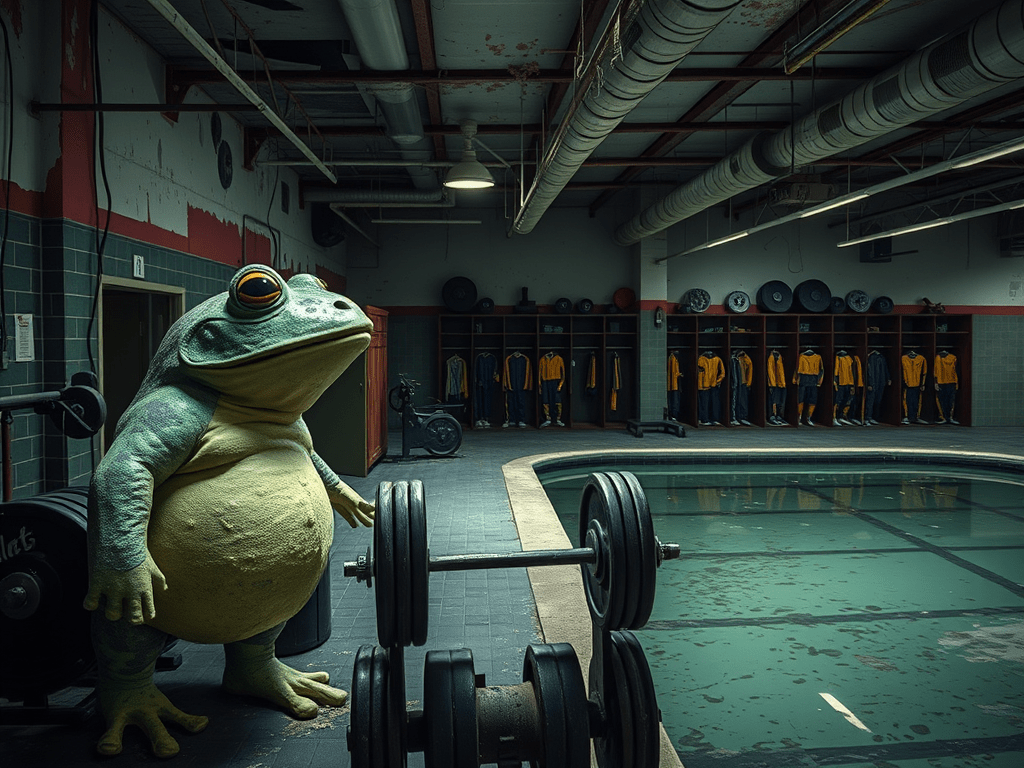

Living in the bottle with Barbara Eden was my unconscious wish to never grow up, to live forever in the womb with my first crush. I realized I had the personality of a man-child who never wanted to enter the adult world in 1974 when as a thirteen-year-old bodybuilder, I had started my training at Walt’s Gym in Hayward, California. Converted from a chicken coop in the 1950s, the gym was a swamp of fungus and bacteria. Members complained of incurable athlete’s foot and some claimed there were strains of fungus and mold that had not yet been identified in scientific journals. Making a home in the fungal shower stalls was an oversized frog. The pro wrestlers had nicknamed the old-timer frog Charlie. The locker always had a bankrupt divorcee or other in a velour top and gold chain hogging the payphone while having a two-hour-long talk with his attorney about his bleak life choices. There was an unused outdoor swimming pool in the back with murky water black with plague and dead rats. A lonely octogenarian named Wally, who claimed to be a model for human anatomy textbooks, worked out for several hours before spending an equal time in the sauna and shower, completing his grooming with a complete-body talcum powder treatment so that when he spoke to you, he did so embalmed in a giant talcum cloud. The radio played the same hits over and over: Elvin Bishop’s “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” and The Eagles’ “New Kid in Town.” What stood out to me was that I was just a kid navigating in an adult world, and the gym, like the barbershop, was a public square that allowed me to hear adult conversations about divorces, hangovers, gambling addictions, financial ruin, the cost of sending kids to college, the burdens of taking care of elderly parents. I realized then that I was at the perfect age: Old enough to grow big and strong but young enough to be saved from the drudgery and tedium of adult life. It became clear to me then that I never wanted to grow up. I wanted to spend my life luxuriating inside the mother of pearl bottle with Barbara Eden in a condition of perpetual adolescence.

Wanting to live in Jeannie’s bottle wasn’t just about being joined to the hip with the one I loved. It was about protection from evil. This became apparent in 1972 when I was ten, and I watched an ABC Movie of the Week, The Screaming Woman. Based on a Ray Bradbury short story, the movie was about a woman buried alive. Her screams haunted me so much that I could not sleep for two weeks as I imagined the mud-covered lady under my bed crying for my help. I swore I would never watch a scary movie again, but a year later when my parents had left for a party, I was bored, so I watched Night of the Living Dead. What I learned from watching these scary movies is that when you see depictions of evil, you can’t “unsee” them. Those visions leave a permanent mark so that nothing is ever the same again. What was once the happy, innocent sound of the neighborhood jingle of the ice cream truck is now a jalopy full of devil-clowns ready to exit the vehicle and kidnap me from my room. I tried to remedy my trauma by watching The Waltons and Little House on the Prairie, but these wholesome depictions of family life could not bring back the innocence that was lost forever, so at age eleven, I was already conceiving my elaborate bunker for the Great Zombie Apocalypse. And that bunker, of course, was Jeannie’s bottle.

In my early teens, my life became a futile quest to find substitutes for living inside Jeannie’s bottle. For example, in 1974 I visited several friends and neighbors who had recently purchased waterbeds, tried them out, and became convinced that waterbeds would afford me a life of luxury, unimagined pleasures, and relaxation that life had so far denied me. I persuaded my parents to buy me one. My love affair with the contraption proved to be short-lived. Its temperature was either too hot or too cold. It leaked. It often smelled like a frog swamp. I remember if I moved my body, there would be a counterreaction, like some invisible wave force fighting me as I tried to get comfortable. One day the waterbed leaked so badly that the floorboards were damaged and my bedroom looked like something out of Hurricane Katrina. What was supposed to be a revolution in sleep proved to be a nightmare, and my quest to find a substitute for Jeannie’s bottle had to be started afresh.

The longing to be inside Jeannie’s bottle is a regression impulse, and I can’t talk about regression without mentioning Cap ‘N Crunch. My mother indulged my appetite for this sugary cereal and bought me all its variations: Cap ‘N Crunch with Crunch Berries, Peanut Butter Cap ‘N Crunch, and then the renamed versions of the same-tasting cereal: Quisp, Quake, and King Vitamin. Quaker cereals took their winning formula of corn and brown sugar flavors and sold several variations with different mascots and names.

As a kid watching these cereals being advertised on TV, it was clear that too much of a good thing was not a problem. On the contrary, I felt compelled to taste-test all these cereal varieties the way a sommelier would taste dozens of Zinfandel wines from the same region or a musicologist would listen to hundreds of different versions of Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony.

Eating six versions of Cap ‘N Crunch afforded me the illusion of variety while eating the same cereal over and over. I was a seven-year-old boy who wanted to believe I had choices but at the same time didn’t want any choices.

You will sometimes hear about the man who is in his sixth marriage and his wives in terms of appearance, temperament, and personality are all more or less the same. The man keeps going back to the same woman but wants to believe he has “found someone new” to give him the hope of a new life.

That was essentially my relationship with Cap ‘N Crunch. Not only was I stagnant in my food tastes, but I was also regressing into sugar-coated pablum. My love of cereal, which endures to this day, was the equivalent of finding comfort in Jeannie’s bottle.

In addition to sweetened cereal as evidence of my emotional stagnation was my choice of damaged role models. While I was fixated on I Dream of Jeannie, my bodybuilding partner Bull was fixated on Gilligan’s Island. Choosing Bull as my role model must have prolonged my delayed development. Bull was not known for his social decorum and gallantry. One example that stands out is that one night we were swimming at the Tanglewood apartments swimming pool when Bull found a giant orange fluorescent bra hanging by its strap on the diving board. It practically glowed in the dark. Bull grabbed the bra and twirled it above his head as if he were going to fling it. Then he stopped and said it was his sister’s birthday the next day, and he had forgotten to buy her a present. He didn’t even wrap it. He just gave his sister this orange bra, and she wasn’t even shocked. For her, it was just another day in the life of having a crazy brother. When I think back to my delayed development in the world of dating and relationships, I have to attribute much of that delay to my misguided choices of male role models. It would be unfair, after all, to lay all the blame on Jeannie. The fact was that I was in love with Jeannie as a fantasy, but as a real woman she terrified me.

This was evident on one warm California spring afternoon in 1973. After sixth-grade classes were over and the bus dropped us off at Crow Canyon Road, we would often walk across the street to 7-Eleven to get a Slurpee before trekking up the steep hill that was Greenridge Road. I was standing inside 7-Eleven with my friends listening to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl” playing on the store radio when the Horsefault sisters, both freckled with long blonde hair and beaming, mischievous blue eyes, came into the store and asked me if I wanted to see a rabbit inside their cage. One was an eighth-grader and the other a high school sophomore. They lived in a farmhouse behind the 7-Eleven. I had no interest in seeing a rabbit inside a cage, but the girls had high cheekbones and figures that reminded me of my first crush, Barbara Eden, so I told them I was very interested in seeing their caged rabbit. I exited 7-Eleven with the girls, and we walked about a hundred yards on a trail that was covered with dry horse dung and surrounded by a field of grass before we reached the outskirts of their farmhouse. Behind a thicket of bushes was a large cage, with the door slightly ajar. A heavy chain lock hung on the door latch. I looked inside the cage, but I saw that there was no rabbit. At this point, the sisters, cackling like witches, grabbed me and tried to drag me into the cage. It was clear that they were attempting to prank me, put me inside the cage, lock the door, and make me their prisoner. But I was too strong for them, and as we wrestled outside the cage and rolled on the grass, we became enveloped in a cloud of dust and hay. In a nearby coop, chickens were clucking and flapping their wings with great alarm and alacrity. When the sisters, now covered in sweat, realized they did not have the strength to carry on with their mission, I fled them and rushed home. I was outraged that they had tried to steal my freedom, and I diverted myself by watching my favorite TV show, I Dream of Jeannie, starring the gorgeous Barbara Eden, who played a lovelorn genie trapped in a bottle except when summoned by her master. Clearly, I was still too young to understand the exquisite pleasures of irony.