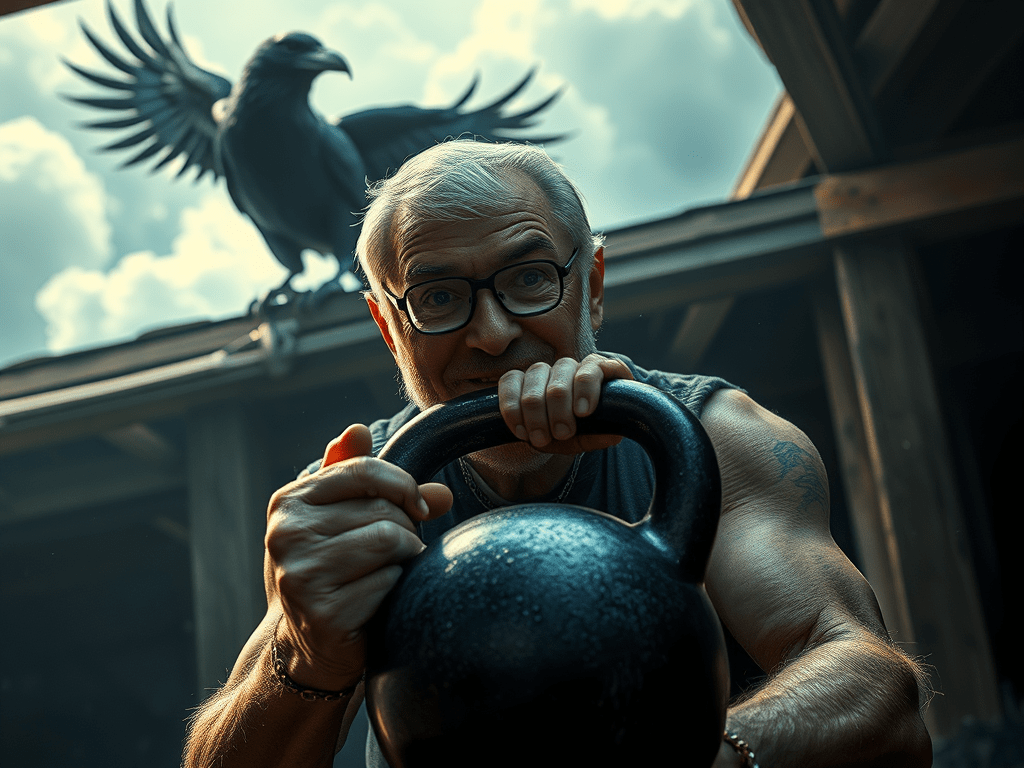

At 63, with fifty years of training behind me and enough injuries to fill a radiologist’s scrapbook, I don’t pay a therapist two hundred bucks an hour to dissect my existential drift. No, I take my angst to the garage and sweat it out under the cold, unforgiving eye of a steel kettlebell.

This isn’t the gym-as-penance nonsense of my youth. I’m in it for the long haul now—grease in the joints, not fire. I train smart. No heroic max-outs, no flirtations with the ER. I chant my gospel, delivered by YouTube prophet Mark Wildman: “The purpose of working out today is to not hurt yourself so you can work out tomorrow.”

Prepped with a concoction of 50 grams of protein (half yogurt, half whey, all optimism) and 5 grams of creatine, I step into the garage like a monk entering a steam-soaked temple. Within minutes, I’m sweating like a politician in a polygraph booth, slipping into that endorphin-laced trance where everything hurts and yet somehow heals.

But my solitude never lasts.

The parade begins: delivery drivers dropping packages by the gate like sacrificial offerings. They nod. We chat. They ask about my workouts. Sometimes they want kettlebell tips, which I deliver like the gym-floor Socrates I’ve become.

Then come the other visitors—the crows. Not just crows. Hypercrows. Schwarzenegger crows. Hulking, obsidian-feathered beasts with the posture of Roman generals and the swagger of barbell-swinging demons. These things don’t fly—they strut. They don’t chirp—they taunt.

One in particular has claimed me. I’ve named him Gravefeather, which feels appropriately mythic. He has the pecs of a cartoon strongman and the gaze of someone who’s seen civilizations fall and isn’t impressed. He parks himself on the fence or the garage roof, staring me down mid-swing with an expression that says, “Your form is garbage and mortality is laughing at you.”

I know he remembers me. Crows do that. He remembers that I’m no threat. He remembers I talk to myself. He probably knows my macros. And when I lock eyes with him, mid-swing, sweat blurring my vision, I swear he’s thinking, “Nice hinge, old man. Shame about your knees.”

Sometimes he’s perched twenty feet away while I’m gasping through Turkish get-ups, his eyes drilling into me with cosmic disdain. I hear him say, without speaking, “Enjoy your little routine, fleshbag. Entropy is undefeated.”

But I argue back. I say, “Just because we’re mortal doesn’t mean we surrender to chaos. This is my sanctuary. I honor it. I will not be mocked by a sentient pigeon in a tuxedo.”

Gravefeather cocks his head. He seems to consider this. Then, with the faintest nod of something like respect, he lifts off into the blue, cawing a tune that sounds like the chorus of a forgotten Paul McCartney song—melancholy, strangely triumphant, vaguely judgmental.

And I return to the bell. I swing. I breathe. I endure. Gravefeather may be watching, but the iron remains mine.