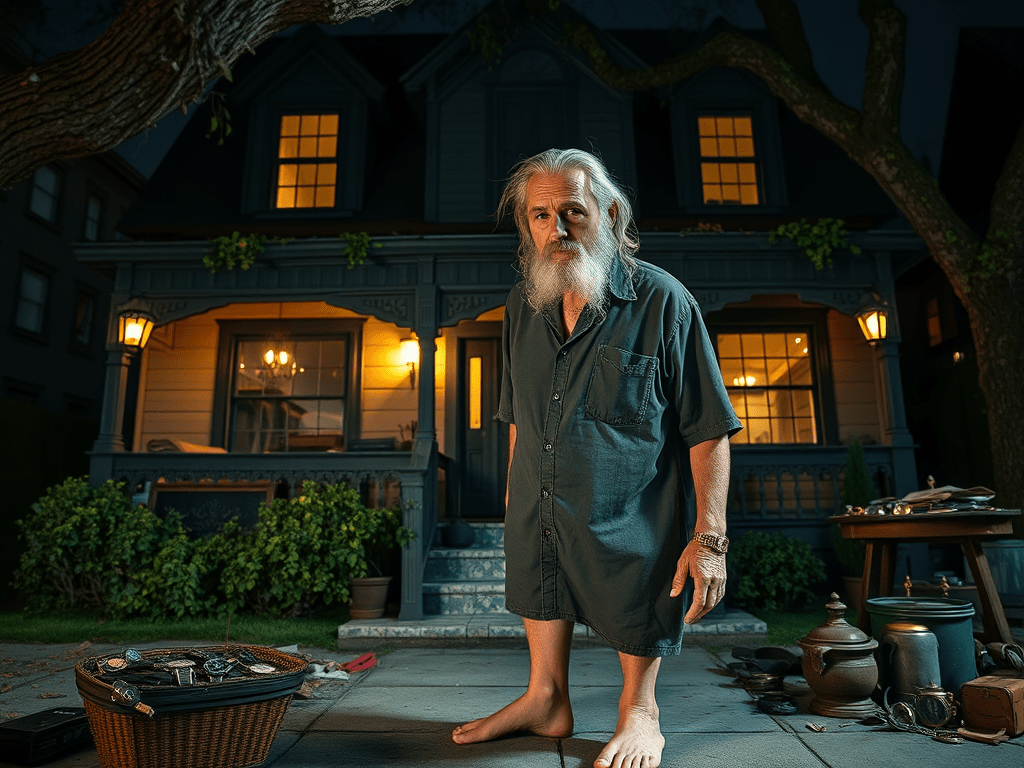

The next evening, under the same milky moonlight and sipping from a chipped mug that looked like it had survived a bar fight, the Watch Master laid it out:

“If you want salvation,” he said, voice gravelly and smug, “you must walk through fire. And that fire, my friend, is called owning one watch. Not three. Not two. One.”

He sipped, smirked, and let the pronouncement hang in the air like incense—or maybe judgment.

My stomach dropped.

“That would mean no Seiko Astron. Not only that, I’d have to sell six watches and keep just one.”

He nodded slowly. “Your math is astounding.”

“But… which one?”

He tilted his head, as if I were asking him what color the sky was.

“You already know.”

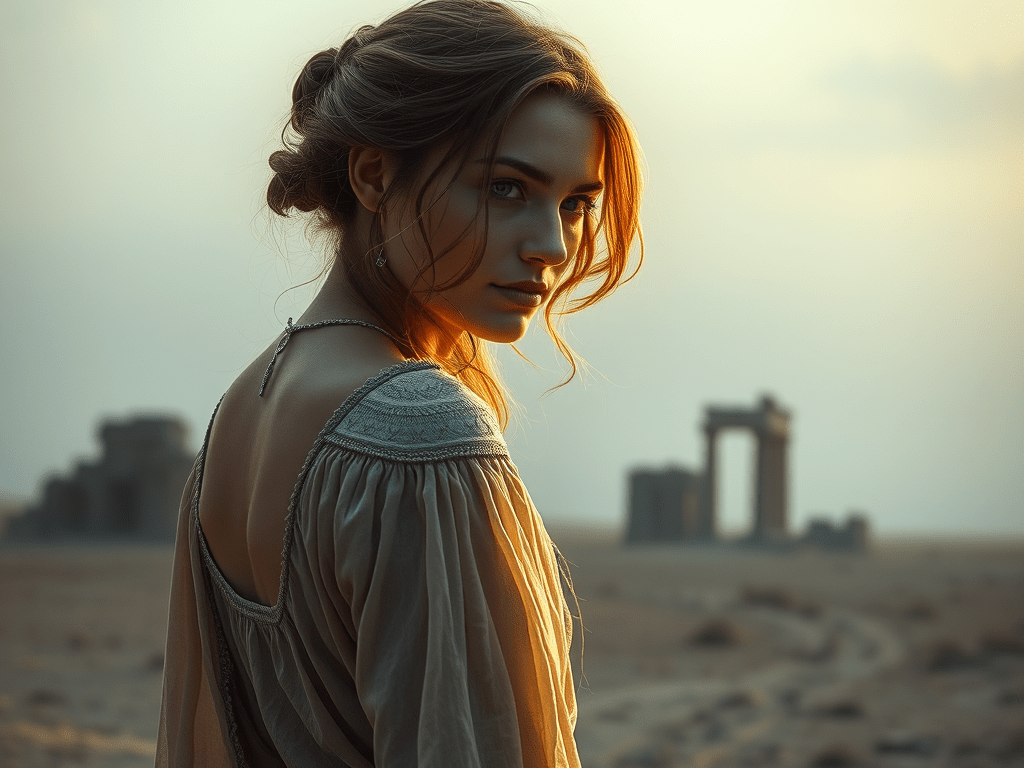

Of course I did. There’s a photo of me on the Santa Monica Pier, the sun melting into the Pacific behind me, gulls circling overhead, breeze in my face, and on my wrist: the Seiko Uemura, black Divecore strap, rugged and unpretentious. That wasn’t just a picture. It was a mirror. That version of me looked content—anchored. Whole.

I told the Watch Master about the photo. He nodded like a man who’d just heard someone read their own obituary correctly.

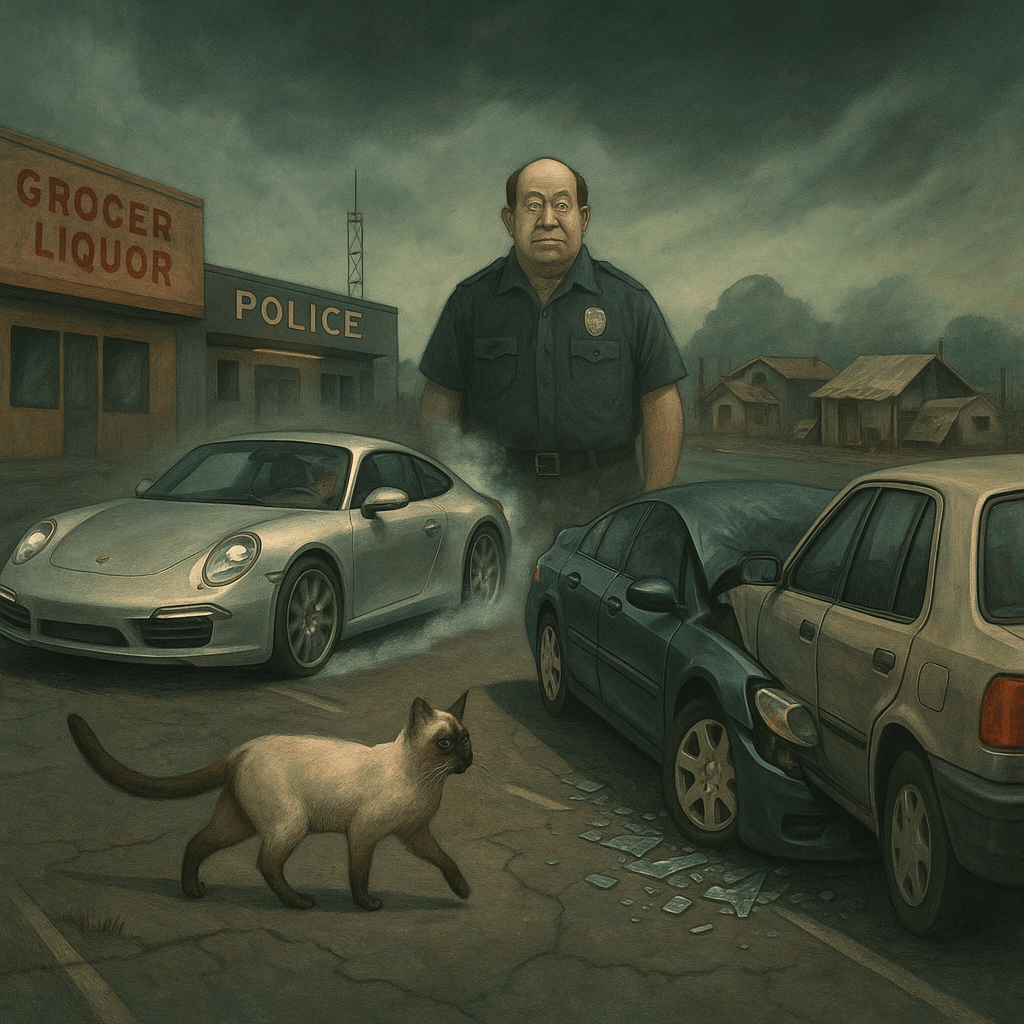

“Every true addict has a signature watch,” he said. “But most of them are too busy playing collector cosplay to recognize it. Instead, they sabotage their joy, clutter their soul, and call it a ‘hobby.’ Worse, they bond with other broken men, enabling each other with dopamine high-fives. That’s where you are. The fray.”

“So I’d have to cut ties… abandon my watch circle.”

“Not a circle. A kennel. A cacophony of barked opinions and Instagram wrist shots. Remember: lie down with dogs, wake up with fleas.”

“They’re not dogs. They’re human beings.”

“Sure. Dogs with Venmo.”

I sighed. “I don’t have many options, do I?”

“You do,” he said. “You can become the bloated lounge demon from your dream, if that’s the life you want. Slathered in regret, bejeweled in denial.”

“How do I get out?”

He leaned in, eyes suddenly sharp.

“You already know.”

“Sell the six,” I said. “Feels like amputating my foot.”

“Better to sell watches than sever limbs. Less blood.”

“So I walk away. Keep the Uemura. Wear it like old jeans and just… let it be.”

“You must die to be reborn,” he said, yawning like a lion after a kill. “But only if you want to. Telling people to choose life is exhausting. Go home. Sleep on it. Come back tomorrow.”

And just like that, he vanished into the darkness of his sagging Victorian like a prophet with bedtime boundaries.