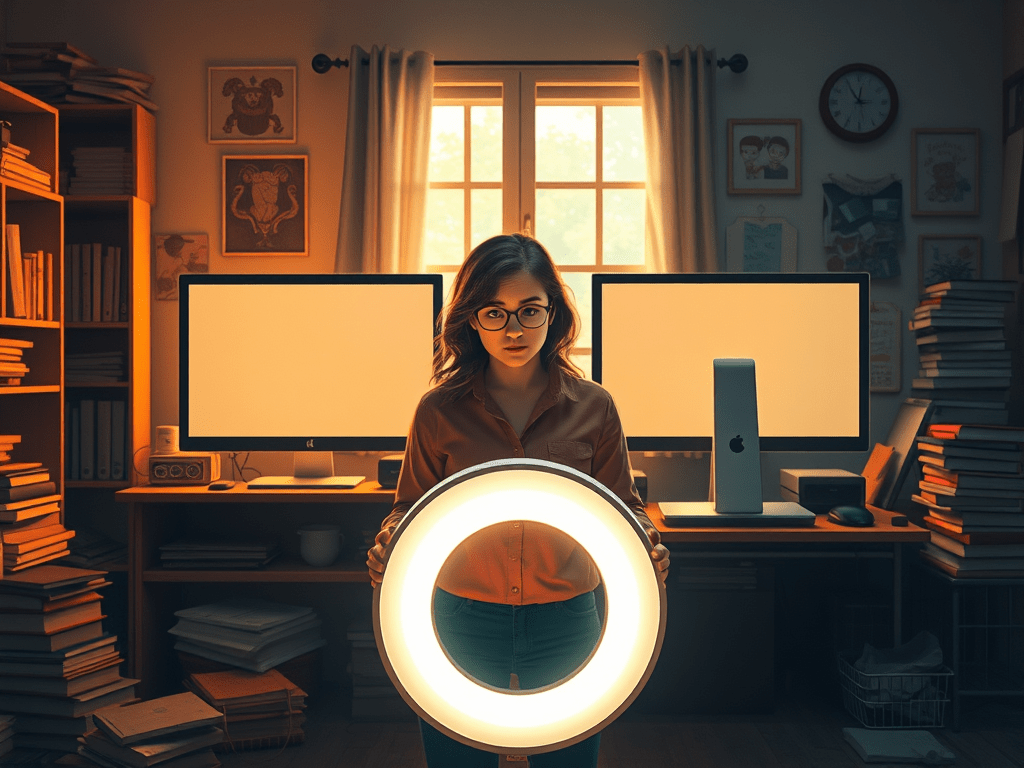

During lockdown, I never saw my wife more wrung out, more spiritually flattened, than the months her middle school forced her into the digital gladiator pit of live Zoom instruction. Every weekday morning, she stood before a pair of glaring monitors like a soldier manning twin turrets. At her feet, the giant ring light—a luminous, tripod-legged parasite—waited patiently to stub toes and sabotage serenity. It wasn’t just a lighting fixture; it was a metaphor for the pandemic’s unwanted intrusion into every square inch of our domestic life.

My wife’s battle didn’t end with her students. She also took it upon herself to launch our twin daughters, then fifth-graders, into their own virtual classrooms—equally chaotic, equally doomed. I remember walking past their screens, peering at those sad little Brady Bunch tiles of glitchy faces and frozen smiles and thinking, This isn’t going to work. It didn’t feel like school. It felt like a pathetic simulation of order run by people trying to pilot a burning zeppelin from their kitchen tables.

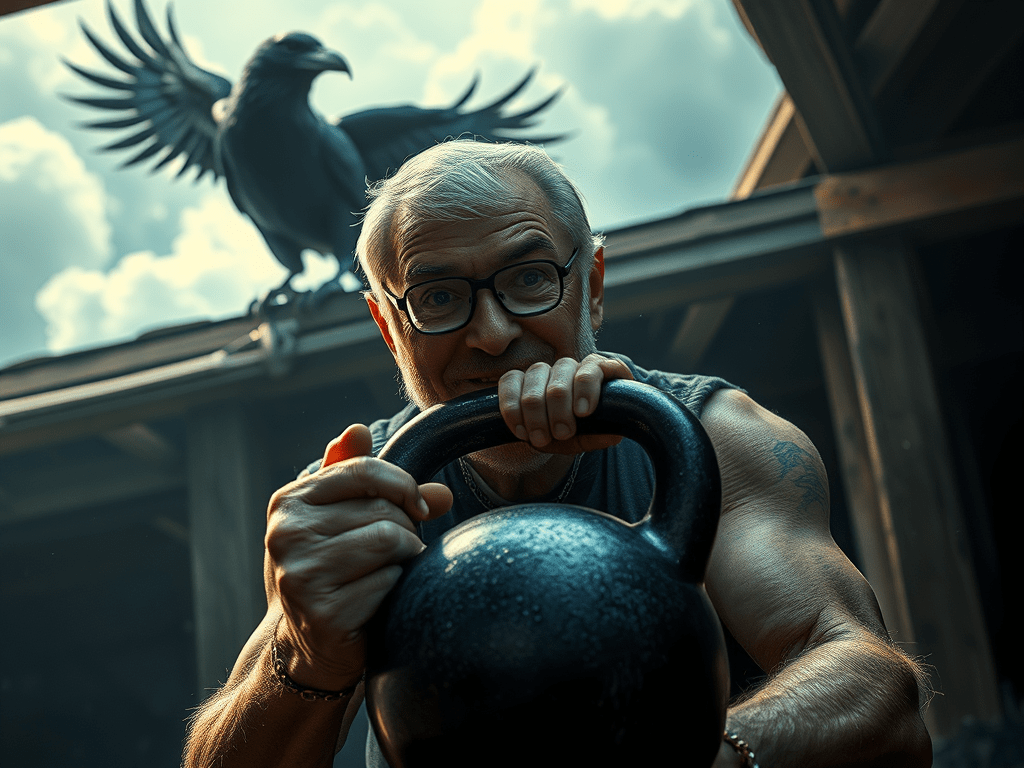

I, by contrast, got off scandalously easy. I teach college. My courses were asynchronous, quietly nestled in Canvas like pre-packed emergency rations. No live sessions. No tech panics. Just optional Zoom office hours, which no one attended. I sat in my garage doing kettlebell swings like a suburban monk, then retreated inside to play piano in the filtered afternoon light. The pandemic, for me, was a preview of early retirement: low-contact, low-stakes, and high in self-righteous tranquility.

My wife envied me. She joked that teaching Zoom classes was like having your teeth drilled by a sadist who lectures you on standardized testing while fumbling with the pliers. And I laughed—too hard, because it wasn’t really a joke.

The pandemic cracked open a truth I still wince at: the great domestic imbalance. I do chores, yes. I wipe counters, haul laundry, load the dishwasher. But my wife does the emotional heavy lifting—the million invisible tasks of motherhood, schooling, comforting, coordinating. During lockdown, that imbalance stopped being abstract. It stared me in the face.

For me, quarantine was a hermit’s holiday. For her, it was a battlefield with bad Wi-Fi. And while I’m back to teaching and she’s back to something closer to normal, I haven’t forgotten the ring light, the glazed stare, or the guilt that hums quietly like a broken refrigerator in the back of my mind.