In his New Yorker piece, “What Happens After A.I. Destroys College Writing?”, Hua Hsu mourns the slow-motion collapse of the take-home essay while grudgingly admitting there may be a chance—however slim—for higher education to reinvent itself before it becomes a museum.

Hsu interviews two NYU undergrads, Alex and Eugene, who speak with the breezy candor of men who know they’ve already gotten away with it. Alex admits he uses A.I. to edit all his writing, from academic papers to flirty texts. Research? Reasoning? Explanation? No problem. Image generation? Naturally. He uses ChatGPT, Claude, DeepSeek, Gemini—the full polytheistic pantheon of large language models.

Eugene is no different, and neither are their classmates. A.I. is now the roommate who never pays rent but always does your homework. The justifications come standard: the assignments are boring, the students are overworked, and—let’s face it—they’re more confident with a chatbot whispering sweet logic into their ears.

Meanwhile, colleges are flailing. A.I. detection software is unreliable, grading is a time bomb, and most instructors don’t have the time, energy, or institutional backing to play academic detective. The truth is, universities were caught flat-footed. The essay, once a personal rite of passage, has become an A.I.-assisted production—sometimes stitched together with all the charm and coherence of a Frankenstein monster assembled in a dorm room at 2 a.m.

Hsu—who teaches at a small liberal arts college—confesses that he sees the disconnect firsthand. He listens to students in class and then reads essays that sound like they were ghostwritten by Siri with a mild Xanax addiction. And in a twist both sobering and dystopian, students don’t even see this as cheating. To them, using A.I. is simply modern efficiency. “Keeping up with the times.” Not deception—just delegation.

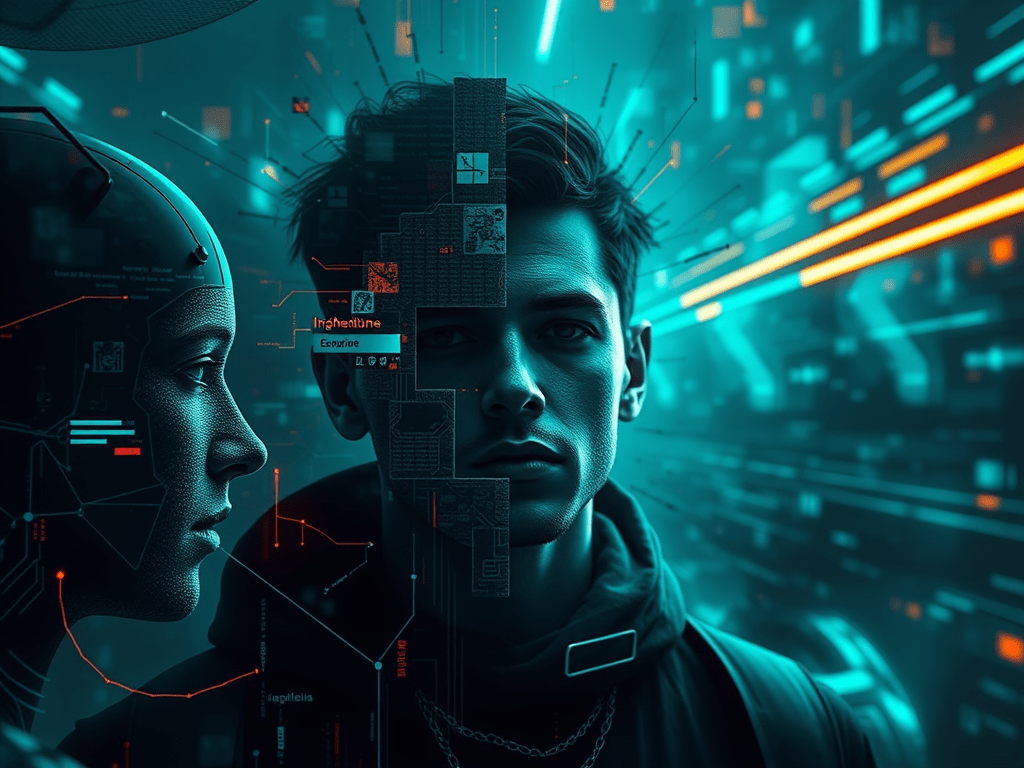

But A.I. doesn’t stop at homework. It’s styling outfits, dispensing therapy, recommending gadgets. It has insinuated itself into the bloodstream of daily life, quietly managing identity, desire, and emotion. The students aren’t cheating. They’re outsourcing. They’ve handed over the messy bits of being human to an algorithm that never sleeps.

And so, the question hangs in the air like cigar smoke: Are writing departments quaint relics? Are we the Latin teachers of the 21st century, noble but unnecessary?

Some professors are adapting. Blue books are making a comeback. Oral exams are back in vogue. Others lean into A.I., treating it like a co-writer instead of a threat. Still others swap out essays for short-form reflections and response journals. But nearly everyone agrees: the era of the generic prompt is over. If your essay question can be answered by ChatGPT, your students already know it—and so does the chatbot.

Hsu, for his part, doesn’t offer solutions. He leaves us with a shrug.

But I can’t shrug. I teach college writing. And for me, this isn’t just a job. It’s a love affair. A slow-burning obsession with language, thought, and the human condition. Either you fall in love with reading and writing—or you don’t. And if I can’t help students fall in love with this messy, incandescent process of making sense of the world through words, then maybe I should hang it up, binge-watch Love Is Blind, and polish my résumé.

Because this isn’t about grammar. This is about soul. And I’m in the love business.