Twenty-six years ago, I lost my classroom key at a university. This was not treated as a minor inconvenience. It was treated as a moral failure.

I was summoned before a college administrator whose demeanor suggested I had been caught shoplifting ideas from Plato. She informed me—slowly, with relish—that the one thing a college instructor does not do is lose his key. She scanned me from head to toe the way a customs agent inspects a suitcase that smells faintly of contraband. My carelessness, she implied, had finally revealed my true identity: a professional bum, a sloth masquerading as an educator, a man unfit to shepherd students through anything more complex than a vending machine.

Once she had finished anatomizing my character, I asked—meekly—how one went about replacing a lost key.

“You don’t just get a replacement,” she said. “It’s a process.”

The word process landed like a sentence.

She explained that I would need to drive to a remote outpost on the edge of campus called Plant-Ops. There, I would meet a locksmith. I would give him my personal information and twenty dollars in cash. No check. No receipt. The arrangement sounded less like facilities management and more like a back-alley transaction involving counterfeit passports.

“How will I know who the locksmith is?” I asked.

“You’ll know him,” she said. “He’s the only person there.”

“What’s the place called again?”

“Plant-Ops.”

I repeated the name aloud, hoping to brand it into my memory. She looked at me as one looks at a child who has accidentally set fire to a jungle gym and informed me that I was dismissed.

Shamed and slightly afraid, I drove east from campus. The pavement gave way to dirt, then rubble, then something that barely qualified as a road. My car bucked and rattled as I passed cow skulls bleaching in the sun and tumbleweeds drifting like omens. Buzzards circled overhead. I was no longer in Southern California. I had crossed into a grim pocket dimension where entropy had been fast-forwarded and everything was quietly rehearsing its own ending. If someone had told me I would die there, I would not have argued.

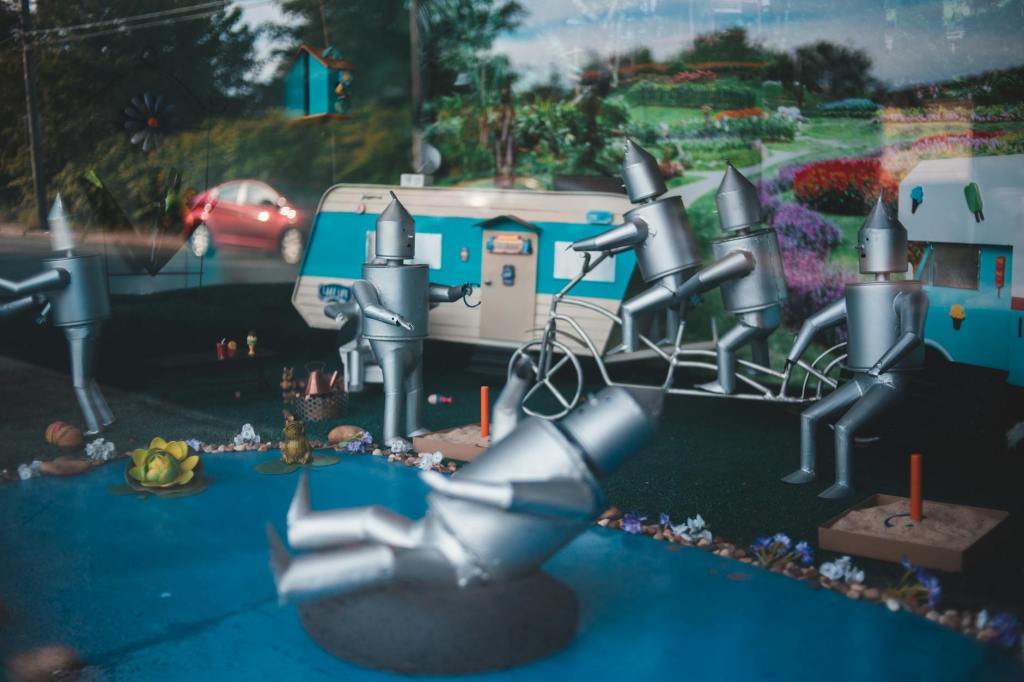

At last, I reached Plant-Ops: a dilapidated hangar that looked one strong gust away from becoming a weather event. Inside stood the locksmith. He was short, grouchy, bespectacled, and gaunt, with a bushy mustache and a few desperate strands of black hair clinging to his bald skull. He wore a grease-splattered apron. Wind howled through the corrugated metal walls, and I half-expected the structure to lift off and spin into the sky like Dorothy’s house.

The man stood over a battered wooden workbench, glaring at me while eating cold SpaghettiOs straight from the can. His eyes bulged with irritation. My presence had clearly ruined his meal. Worse, it confirmed his theory of the world: incompetents abound, and today one had wandered into his hangar.

I explained that I had lost my key. I apologized as though I had personally engineered his inconvenience. He demanded twenty dollars in cash—up front—made the key, and then leaned in to warn me that he was retiring soon. His replacement, he said, was a complete idiot, incapable of making a functional key. I took this prophecy seriously.

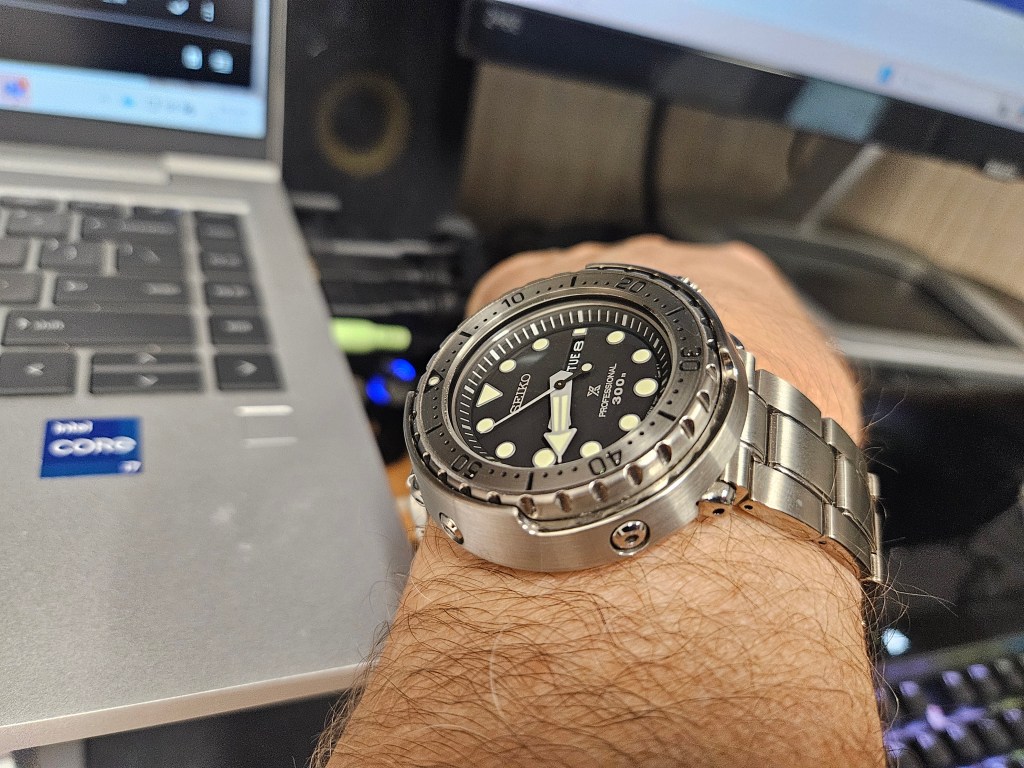

I fled the hangar, drove directly to a hardware store, and purchased a Kevlar keychain with a tether reel, a high-density nylon belt loop, and enough industrial reinforcement to secure a small boat. From that day forward, my keys were attached to my body like an ankle monitor.

I have done worse things in my life—objectively worse—but for reasons I still don’t fully understand, losing that key put me briefly at odds with the universe. I had been consigned to a shame dungeon, escaped it by the skin of my teeth, and sworn never to return.