When I think of Sigmund Freud, I don’t picture the sober father of psychoanalysis so much as a man presiding over an endless therapy session in which a poor soul reclines on a tufted couch, excavating their psyche with the zeal of a Siberian prisoner digging for coal. I tend to side with podcaster Katie Herzog here: all that navel spelunking doesn’t yield much juice for the squeeze. My mental health cure is more prosaic—get out of my head, do the dishes, help someone else, and remind myself that brooding isn’t a spiritual distinction but simply the human condition, dressed up in self-importance.

That said, Freud remains a cultural heavyweight, a sort of St. Paul of the psyche. Both men dove into deep, uncharted waters: both charting neurosis and the divided self from different angles. Their remedies were at odds—St. Paul promised redemption; Freud essentially said, “There is no God. Buck up, buttercup.” But there’s always a third way. Perhaps we can podcast our way out of despair. That thought struck me as I read Rebecca Mead’s New Yorker profile of Bella Freud’s “Fashion Neurosis.” Sigmund’s great-granddaughter, Bella isn’t exactly a scholar of the old man’s work, but she leans into his therapy tropes with sly cosplay. Guests flop onto the proverbial couch, confess their quirks, addictions, and philosophies, and tie it all back to their fashion obsessions. Clothes become the psyche’s fabric, quite literally.

As for me, Bella probably won’t be calling. My claim to fame is enjoying oatmeal for dinner. Still, if she ever asked, I’d come armed with a story. In kindergarten, I had my prized “Monkees pants,” green checkered flares with a radioactive sheen, worn proudly for Show and Tell as I belted out the Monkees’ theme song. Girls swooned, begged for autographs, and I was five going on Micky Dolenz. Then came my Hulk phase: mutilating brand-new jeans so it looked like my swelling muscles had shredded them. My parents adored this use of their clothing budget. Later, the bodybuilding years brought muscle shirts and tight jeans, followed by my “uniform” phase: gray golf shirts, boot-cut jeans, tennis shoes, repeated ad nauseam for three decades.

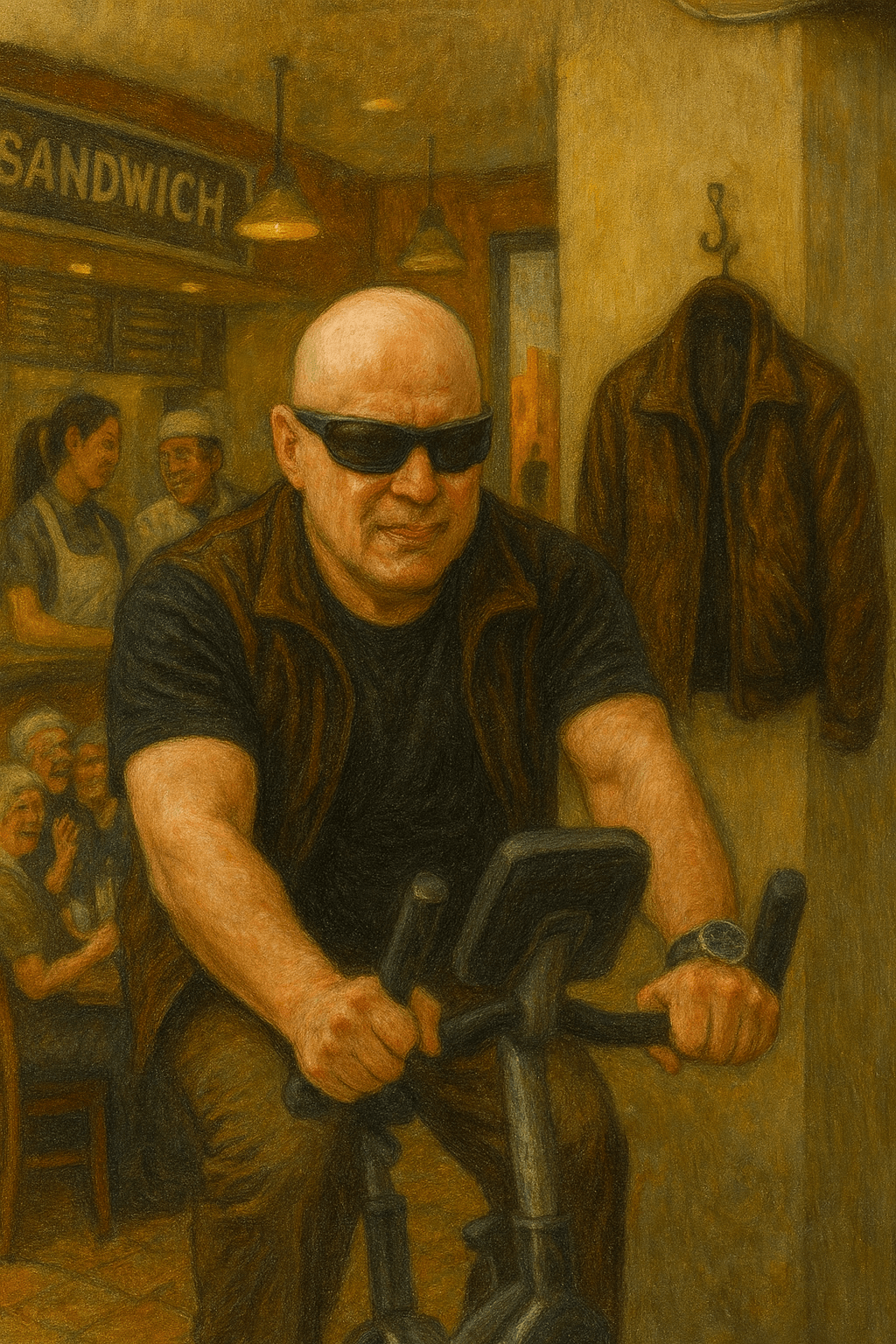

My magnum opus, however, is what I call Triple Lounge Wear. A gray tank top and Champion shorts serve as daywear, pajamas, and gym attire—a holy trinity of frictionless fashion. Why cycle through outfits when you can be a one-man capsule collection of sloth and efficiency?

Naturally, no discussion of fashion would be complete without confessing my incurable diver watch obsession. My imagination is still shackled to childhood visions of Sean Connery suavely flashing a Submariner on a NATO strap, or Jacques Cousteau backstroking with porpoises while his orange-dial Doxa Sub 300 glowed like a miniature sun. Compared to that, what hope does any outfit of mine have? A diver watch isn’t an accessory—it’s the anchor, the crown jewel, the only thing saving me from looking like a man in oatmeal-stained gym shorts pretending he has style.

Bella Freud would beam at my ingenuity, then lower her voice and ask, “So Jeff, tell me about your childhood.” And I’d answer, “Well, it started with the Monkees pants…”